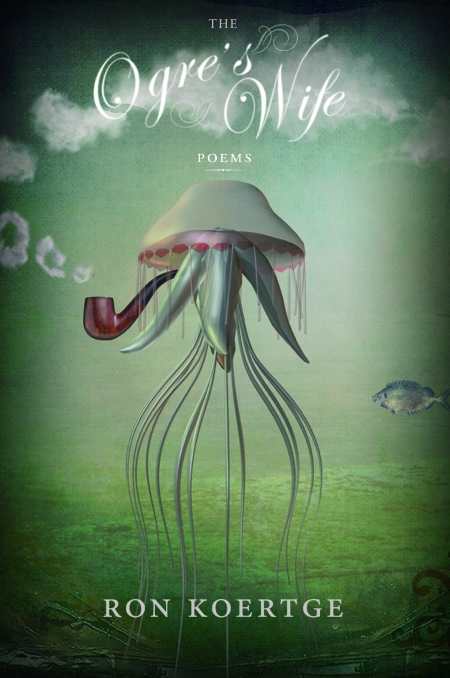

The Ogre's Wife

To subvert happily-ever-after, this poet populates his verse with grim Grimm characters and sprinkles in some dark humor.

Ron Koertge—fiction writer, recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the California Arts Council, and author of numerous poetry collections, including his previous Red Hen Press titles, Fever and Indigo—returns in his latest work with conversational personae found in mythology, fairy tales, Christian lore, and film noir, among other sources.

From Icarus to Little Red Riding Hood, martyrs to Bette Davis, Koertge navigates between pathos and offbeat humor, revealing frequently dark consequences and little- or un-assuaged loneliness. In “The Gingerbread Man,” a wife constructs a lover only to watch her husband consume him; in “The Invisible Man,” the death of a child leads the title character to contemplate revenge through “[s]trychnine in a cocktail”; in “Jack,” plundering the giant’s gold results in a lifetime of guarding against thieves—all of which play against happily-ever-after endings.

Readers familiar with Anne Sexton’s Transformations and other collections that mine Grimm characters will find that Koertge similarly departs from and enhances the original tales. His contemporizations may succeed best, however, when they fuse recognizable elements with menace, as when Little Red Riding Hood remarks: “I think about the woodsman. Without him I’d be dead. / But when I remember the wolf, snipped open like a pouch, / I cry and my husband stops what he is doing and kisses / my eyes, the better to see him with.” Throughout the book, lovers join and separate through charged yet direct scenes, while secondary themes of aging and coping with death enrich the work.

Poems on these iconic figures intersperse with gently self-deprecating observations on being a poet and writing poetry—including solitude and the tendency for some writers to take themselves seriously—which are less rewarding in their reflexivity. Still, the whimsical and academic cleverly converge in “The Death of Hansel,” when Gretel enrolls in a creative writing class, and in “The Ogre’s Wife,” when the titular character writes in blood.

Koertge’s range of approaches—including prose poems, haibun, a poem written as a questionnaire with multiple-choice answers, and another penned as a letter to a consumer—also deserve mention for their ability to engage and delight. In its finer moments, The Ogre’s Wife turns the archetypal into subtle points of entry for reflecting on passion. Beneath the glib voices, toughened survivor-mentalities, and pared language, an appealing vulnerability emerges. Here, the storybook comes disconcertingly and achingly close to life.

Reviewed by

Karen Rigby

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.