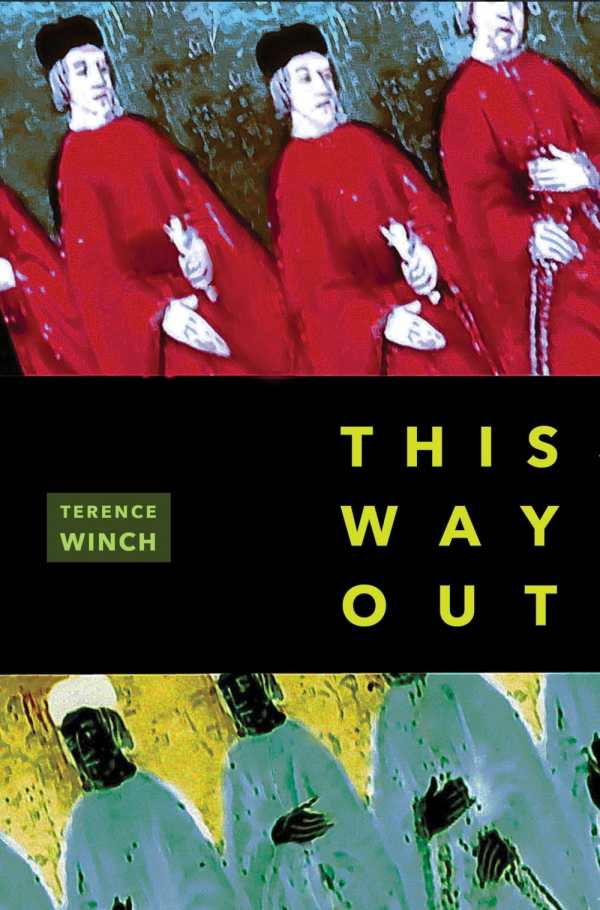

This Way Out

Contemporary references and colloquialisms deepen these poems’ sense of wisdom about human nature.

With This Way Out, Terence Winch offers poems that expose the rawness of life with a fierce and unapologetic bite that is sullenly aware of the tenderness caused by bruising, heartache, and age.

Winch’s poems call forth little of the natural world but much about human nature. Truths are conveyed the way they might be in an obscure Polaroid picture rather than a grand landscape or fine portrait. Uncomfortable poems like “Cows” and “How I Lost My Virginity” explore our culpability in slaughtering animals for their “succulent meat,” or in remaining friends with a person who is a child molester. Such pieces make us curious about the speaker and about ourselves—about the surprised person in the Polaroid shielding his face from the camera’s eye. Winch seems to capture such moments for the same reason many poets revel in nature—because they are life.

Rather than precise turns of phrase that evoke fine impressions, Winch offers bold strokes of plainspoken language. The first line of the collection reads, “I threw my life in the dryer / and let it spin around like mad / at high heat for more than an hour / and now it is bone dry.” He frequently uses words like “ain’t” and explicit vulgarities, and references email, lubricants, and cigarettes. This lack of pretense, combined with a shifting musicality teased out through intelligent line breaks and inconsistent rhymes, makes Winch’s poems accessible and engaging.

This is a largely masculine work, with many references to sex, drinking, music, pubs, and male relationships that harken, in some ways, back to Beat culture. Women are indeed welcome here, but other men might best understand the camaraderie detailed in pieces like “Our Next Breath of Air” or “Classical Instructions.”

The rawness of Winch’s collection is most deeply felt when the poet is vulnerable: in “The Moor Child,” about his son, or in “Two Girls,” about being paralyzed, unable to help two teenagers in a perilous situation. This vulnerability is most evident in the final poem, “Never Say Die,” where Winch writes about the bawdy, tender desperation with which he loves this world: “Okay okay okay. / I won’t die, ever. I won’t cry, ever. I won’t / try to kiss you, except this one time. I will / sneak a smoke with you.” Both tree and forest are revealed here—the poet’s own desire to live, and where every single one of us is headed, regardless of our yearning.

Reviewed by

Margaret Fedder

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.