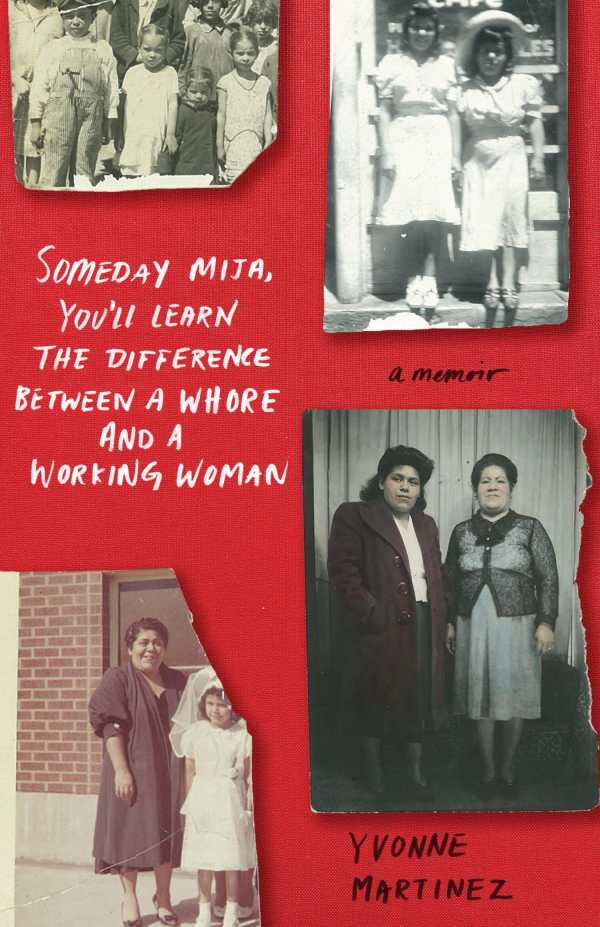

Someday Mija, You’ll Learn the Difference Between a Whore and a Working Woman

A Memoir

A record of discoveries that mirror the paradoxes of a changing, surviving Mexican culture abroad, this memoir exemplifies the complexity of immigrant identities.

Yvonne Martinez’s accomplished memoir-in-essays blends memories with research to resolve her family’s ancestral mysteries.

As a young child, Martinez lived with her great-grandmother, who told her that funerals are where the truth comes out: people “mock the public lie told about themselves and the deceased.” For generations in Salt Lake City, Martinez’s family survived by running a series of Mexican restaurants and other “businesses the Mormons patronized but couldn’t own.” Over the decades of those generations, secrets piled up like snow in the cold Utah winters, and they followed Martinez and her siblings when their parents picked up and moved to South Los Angeles.

The book is composed as a series of short scenes and anecdotes that zigzag through time, with the near present illuminating the deep past and vice versa. English and Spanish weave together like ribbons that join the past, present, and culture, demonstrating the enduring nature of inheritance. As children, Martinez and her siblings recast traditional Mexican myths into their daily English-language life. The “Bloody Bones” ghost they feared, who lived in the abandoned house next door, was their version of Mexico’s La Llorona, a dead woman who searches without end for the children she drowned in her grief. “Mexicans throughout the diaspora,” Martinez writes, “hear her cry for all lost children.”

Martinez’s deepest family secrets concerned violence against children and women, including the loss of three babies. Her recovery from multigenerational personal and political traumas is a central theme in the memoir. Interpersonal violence is set in the context of other hierarchies: as Catholics and Mexicans living in a city run by white Mormons, Martinez’s ancestors reacted in different ways to incidents of religious and ethnic prejudice, and to the oppressive, “LDS only” atmosphere. Martinez writes that her mother avoided whites in a somatic way: “Mother’s aversion was so subversive, I don’t think even she saw it.” Other ancestors, Martinez discovered, resisted oppression and racist violence in more overt ways.

“The thing about secrets is that they don’t want to be secrets. They want to be told,” Martinez writes. In her family, which exists “just out of reach, never realizing its beauty, only the brutality of hard surfaces and the fear of falling off the edge,” the secrets that were exhumed clarify not just the history of Martinez’s ancestors, but also her personal path toward labor activism. On a wider scale, Martinez’s discoveries mirror the paradoxes of a Mexican culture that both changes and survives, exemplifying the complexity of immigrant identities.

Someday, Mija, You’ll Learn the Difference Between a Whore and a Working Woman is a memoir that turns time on its head, circling through terror and joy with eloquence and becoming its own sacrament of resistance.

Reviewed by

Michele Sharpe

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.