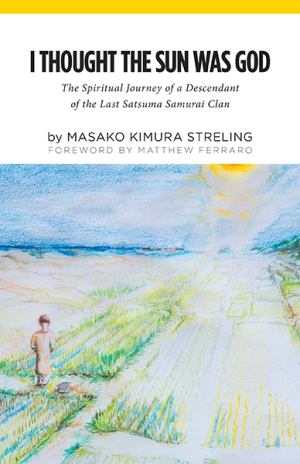

I Thought the Sun Was God

The Spiritual Journey of a Descendant of the Last Satsuma Samurai Clan

“I was raised in two different worlds,” Masako Kimura Streling writes in I Thought the Sun Was God, “one held my paternal grandfather as a remnant of the Satsuma Samurai and his son, while the other held my father and my mother, an Okinawan living in Ishigaki island with a peculiar culture all its own.”

To these two worlds, which came crashing down about her as a teenager in 1945, Streling adds at least three more in a story that spans nearly eighty years: post World War II Okinawa, America of the 1950s through 1980s, and finally current day Japan, where she served as a lay missionary at the turn of the millennium. Moving among these many worlds makes her story an intriguing, engrossing, and eye-opening tale, one that deserves a special place in any women’s studies course or any class on modern Japan.

The most detailed and interesting are early chapters where she describes the near-feudal society of Okinawa and the impact of Japan’s crushing defeat upon that society—and her family. Streling grew up needlessly poor due to the hard-hearted propriety of her Samurai-descended grandfather, who could not bear the humiliation of having his son marry a peasant woman, and one of what was deemed lesser racial stock.

When she marries an American and emigrates to the United States, she meets with yet more discrimination, being labeled a “war bride,” which her co-workers at Japan Airlines equate with being “a loose woman, a prostitute.” Streling’s struggle is made even more difficult by the failing health of her father and her own physical ailments.

This first half of the book is as moving as it is fascinating, and as revealing of the culture and morays of the worlds the author moves about as it is engrossing. Her feelings for the young kamikaze pilots who courted her before leaving on their doomed one-way missions are particularly poignant, as are her observations on society and daily life on Okinawa during and immediately after the war. These one hundred or so pages should be required reading for any who want to know what life was like for the people, and especially the women, of Okinawa in the 20th century.

The second half of the book is a completely different story. It begins with her “spiritual journey,” where she discovers and converts to Catholicism. Raised in a culture where the emperor was god, to have the god himself deny his divinity as part of the surrender in 1945, Streling found herself spiritually adrift. Despite rising from “the life of dire poverty” to one of material excess, something was missing. How she found faith—and how she and her husband tried to live and share that faith with others as lay missionaries back in Japan—is the subject of the second half of the book.

While this half does offer a unique look at the attempt to spread Christianity in Japan, it is not as compelling as the first part of her story, nor as dramatic. The final chapters are marred by her rage at how she believes she and her husband were mistreated by the church. Even if indeed warranted, it reads like an angry diatribe. That she is trying to move past that anger while retaining her faith does her credit, and this book is obviously part of that healing process.

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.