Death Zones and Darling Spies

Seven Years of Vietnam War Reporting

Personal and human stories on the Vietnam War are matched by insightful exploration of political and military strategy.

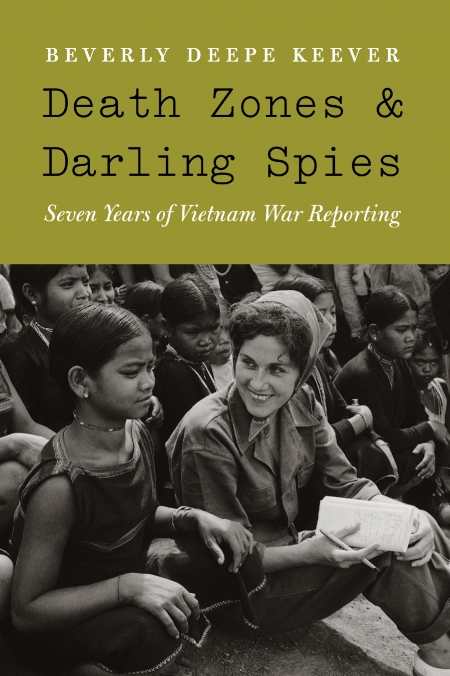

“Marines don’t allow women with legs down there,” a grizzled colonel told Beverly Deepe in 1962 when she sought permission to leave Saigon and accompany a helicopter raid into the jungle. Undeterred, the then twenty-six-year-old journalist, one of the first women to cover the war, borrowed a set of fatigues and went on the mission.

Death Zones and Darling Spies is packed with scores of similar anecdotes from a reporter whose copy was initially trivialized as “lipsticked” perspective on a new and unfamiliar war. By the time she left Vietnam seven years later, Deepe was one of the most respected correspondents in country. Other journalists came and went, but she stayed, mesmerized by the insanity, the courage, and the suffering that was Vietnam.

Although her career spans half a century—first as a reporter and later as a professor—it is of her time in Vietnam that Beverly Deepe Keever seems most proud. Her book is no mere collection or collation of her reports (although a complete list of those is provided in one appendix); it is a solid history of the American involvement in Vietnam. She draws on interviews with generals and politicians, American marines, captured North Vietnamese soldiers, Buddhist monks, and Viet Cong officials, many of them women. There are gripping episodes of being besieged at Khe Sanh and other forts, of accompanying troops as they battle street by street through Hue during the Tet Offensive, and of going on patrols deep into the jungle.

Keever’s very personal and human stories on the war are matched by insightful exploration of political and military strategy. Very early on she saw the “warning signs of a flawed policy” and repeatedly included in her reports comments from those in the field—American and Vietnamese, ally and foe. As one source tells her, “The United States has made more ‘Viet Cong’ than it has killed.”

The eleven chapters are richly illustrated with nearly thirty photographs—arranged not chronologically but instead by topic. In this way, she shows the progression of Americanization, the evolution of strategies, and the devolution of Vietnamese society throughout the course of her seven years in the war zone. She also draws on “The Pentagon Papers” and other books and reports, as noted in the extensive footnotes and second appendix, to fold into her story the military decisions that were made in Washington, usually in secret and very often behind a veil of lies.

Beverly Deepe Keever is a brilliant journalist, and her book is both a personal journal and a journalist’s personal perspective on a long war.

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.