What Remains Is Hope

What Remains Is Hope is an affecting historical novel about a Jewish family’s experiences of World War II.

In Bonnie Suchman’s poignant historical novel What Remains Is Hope, a Jewish family is shattered and reshaped by the rise of Nazi Germany.

The story follows four cousins—Gertrud, Bettina, Trudi, and Gustav—from their close childhood in 1930s Frankfurt through the Holocaust and back to their reunion decades later. Before World War II, the cousins share joys and rivalries under the shadow of rising anti‑Jewish laws; their family discussions highlight the growing political strife, and they debate action versus complacency. Trudi reads government propaganda aloud to her ailing father, her cadence beset by hesitancy as her fear of discovery mounts. When the war breaks out, the cousins are scattered. Indeed, the book’s pace quickens after its opening to convey the relentless tension of life in war-torn Europe.

The cousins have differing experiences of the war: Gertrud, who has “blue eyes and blond hair, just like a real German girl,” is urged by her mother to conceal her Jewish heritage. Cunning, she masterminds an invisible ink system for use during the war. Meanwhile, Bettina fights to protect her son, Trudi navigates occupied France’s dangerous networks, and Gustav endures capture, exile, and forced labor at a concentration camp, clinging to his memories and a book of beloved poems. Their individual choices carry moral weight against the rise of a tyrannical government. Later, in 1996, the surviving cousins gather in Frankfurt to memorialize what was lost.

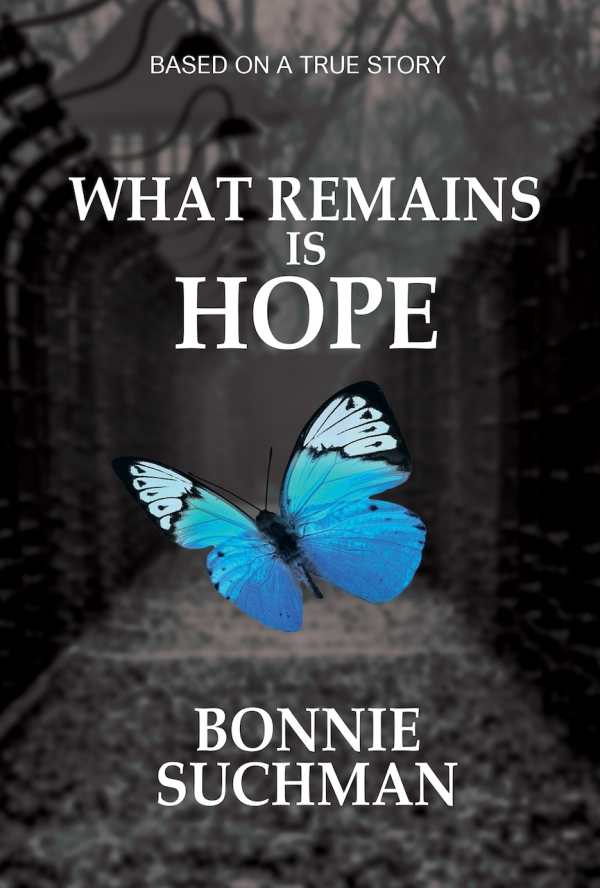

The prose is accessible, blending straightforward narration with keen observations, as of how Trudi “looked like she had just stepped out of a fashion magazine,” her “bobbed auburn‑colored hair” described with tactile simplicity. Later, Gustav is said to have “turned into a blue butterfly” and Gertrud recalls a “Pandora’s box and the butterfly of hope,” imbuing grief and longing into a clear metaphor. And early on, a cinematic depiction of the cousins’ life before the war is shattered by deportation orders, coded escapes, and painful separations.

Told via discrete, interlocking vignettes, marked with their dates and locations, the book includes sharp transitions between scenes, often effected during moments of tension: The awful conditions in the concentration camps, covered moments before, resonate as another cousin contends with dwindling food rations. Details accumulate to reflect the nation’s shift toward authoritarianism, from posters depicting increasing antisemitism to a person sleeping in a tailor’s shop after being evicted. Later, a sense of the banality of war comes through Gustav’s camp routines and as Bettina pretends normalcy while sweeping up brick and glass after a bombing.

The novel’s stakes are established early: The prologue centers the cousins’ return to Frankfurt, with a single chair empty. The meaning of the empty chair becomes apparent as the novel moves from the prewar normalcy through wartime hardships toward the cousins’ eventual reunion. The conclusion is cathartic, focused on the power of memory and desires for a better future.

Cousins’ bonds endure through secrecy, separation, and survival in the moving historical novel What Remains Is Hope, about how four lives are upended by the rise of Nazism.

Reviewed by

John M. Murray

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.