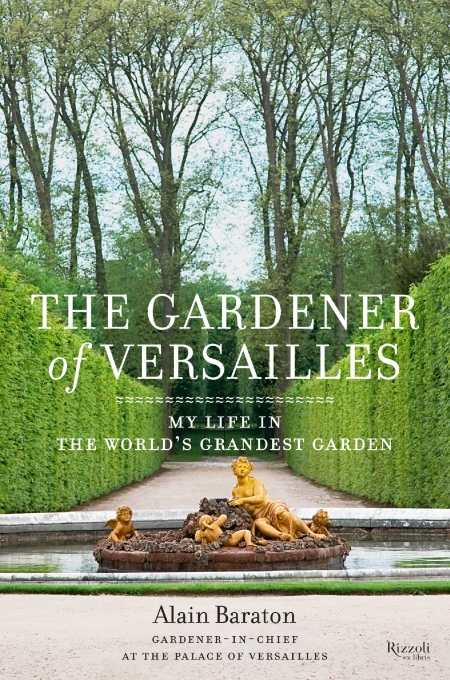

The Gardener of Versailles

My Life in the World's Grandest Garden

- 2014 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Biography (Adult Nonfiction)

Darker moments balance the portrait of a place marked as much by seasonal change as by its irresistible mythology and history.

Gardener-in-chief Alain Baraton reveals the Palace of Versailles—seat of the former monarchy, symbol of opulence, tribute to the arts, and also the site of famous landscapes—as a wilder, often-overlooked treasure. In his capacious, generous memoir, Baraton beautifully renders the intersection of personal memories with French history and botanical splendors.

Baraton, who did not intend a career in gardening but who discovered that the work entwined with his natural inclinations, provides cogent insights and imaginative forays that reveal how “Majesty and intimacy are two sides of the same coin and define the character of the place like none other.” Chapters deftly weave anecdotes on several of the palace’s famed residents (the Sun King, Marie Antoinette, courtiers, and mistresses); stories behind the statuary, artwork, and notable features of Versailles; theatrical spectacles of the past; Baraton’s own first years in the garden; and contemporary encounters with tourists, lovers, eccentrics, and locals. The author recounts much of this with gentle humor. The gardens of Versailles, however, are not entirely romanticized by Baraton. Darker moments, from the aftermath of a storm to suicides, balance the portrait of a place marked as much by seasonal change as by an irresistible mythology.

Amid the grandeur of Versailles, however, it is the human touch Baraton extols, and this quality resounds throughout. When passages magnify nooks and curiosities with renewed wonder, the writing reveals an attentive spirit. Small irregularities in otherwise formal terrain, unique knowledge handed down from other gardeners, personages such as the playwright Molière (in whose former home Baraton resides), sounds heard during strolls after hours, graffiti in the Orangerie, and other everyday details become as entrancing as the larger stories that unfolded under the Ancien Régime. Some of the book’s more compelling sections highlight nearly forgotten figures who became key players in the development of the grounds, including Le Nôtre, an architect, and La Quintinie, a botanist.

The search for personal connection turns toward the practical in the chapter “Dead Leaves,” in which the author explains his preference for earlier gardening methods over the pollution and nuisance of modern equipment—not out of nostalgia, but with the conviction that making allowances for convenience’s sake has lead to gardens with graceless uniformity. Firm views on an increased detachment between workers and the land broaden to reveal a general philosophy on life that is perhaps best summed up by these thoughts: “In the end, it’s a simple question of rhythm and harmony. What is the point in doing things more quickly?”

This engaging account of decades spent cultivating pathways speaks volumes on public and private uses for gardens and of nature’s enduring witness.

Reviewed by

Karen Rigby

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.