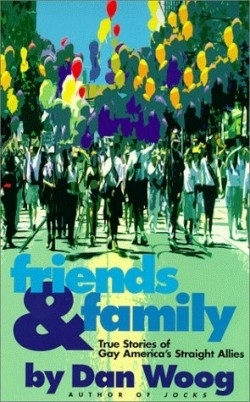

Friends & Family

True Stories of Gay America's Straight Allies

Several notable works of late-millennium journalism profile ordinary people. Studs Terkel’s Working, a series of interviews with members of the American workforce, is a good example of this. More recently, Alan Wolfe, in One Nation, surveyed the responses of 200 Americans to questions about morals and values. Dan Woog’s Friends & Family is a worthy addition to this canon. Woog drew his inspiration in part from Wolfe’s work, noting in the introduction that while Wolfe found most of his subjects “surprisingly nonjudgmental on such issues as race, religion, and family…[m]ost of the people [Wolfe] talked to were not prepared to accept homosexuality.” Woog’s response to this fairly random inquiry was to take a very targeted survey of his own. He used the Internet to seek and screen three dozen straight individuals and couples who have gone beyond accepting particular gay, lesbian and transgendered relatives and friends to advocate for legal and social change at the community and national levels.

Most of the book’s short essays focus on parents of gay, lesbian and transgendered individuals. (As used in this review, the term “gay” includes all these groups unless the context indicates otherwise.) Woog’s other subjects include children of gay parents and couples; Dan Foley, the lawyer who struggled to legalize same-sex unions in Hawaii; teachers; spouses and clergy. Several of the book’s heroes and heroines are the products of churches, organizations and communities whose core values exclude gays. This exclusion leads to their official or unofficial ostracism when they publicly express loyalty to gay relatives or friends.

Woog’s subjects include many parents who have lost gay children. As a premise, this does not sound unusual. What is unusual is the cause of death. An overwhelming number of gay teenagers commit suicide. Some do it before they ever come out. Some take their lives after they are outed involuntarily; some after having a sexual experience; others before they have tried sex. Peer harassment is a very big factor in these pages. Fourteen-year-old Robbie Kirkland, whose mother is profiled in the book’s first essay, was literally harassed to death by his schoolmates. They called him gay because he was different, and he denied his sexuality even more vehemently as a consequence.

A theme that emerges from some of Woog’s accounts is the prevalence of gay-related hate speech among children of all ages. Kids who seem different are routinely called queer, gay or faggy. It would be interesting to know how many straight kids kill themselves-or others-after enduring years of taunting along these lines. In recent media coverage of the Littleton, Colorado, shootings and other violent outbursts by young people, the perpetrators are often identified as “different” by their peers. It would also be interesting to know what kind of name-calling their differentness provoked.

One crusader against such taunting is Sol Kelley-Jones, the 11-year-old straight daughter of a lesbian couple, who advocates for safer schools and other issues affecting children and families. Kelley-Jones took a survey of fourth- and fifth-graders. Only one-fourth of the students she surveyed knew anyone who was gay or lesbian. However, out of eighty-eight students surveyed, sixty-two had heard someone at school call someone else a name that meant “gay” or “lesbian” as a means of making fun of them.

Obviously, gay-bashing can start before anyone involved knows what he or she is saying, other than that they’re talking about someone they don’t like. This is illustrated by the (mostly vague) responses to Kelley-Jones? question, “(W)hat is there about a person that tells you that they are gay or lesbian?” Answers included: “Boy walks like girl”; “They walk and dress in a weird way”; “They wear sweaters a lot”; “Because they look gay”; “When a man is wearing a bra”; “The way they look.” “About how they act,” and “By how they look at another person’s behind.” Some of the pejoratives the students identified as gay-related included “gay bird homo,” “fag,” “queer,” “you love another boy” and “gaggot.” However, they also thought more general epithets were gay-related: “you bitch,” “gross,” “don’t come near me” and “yuck!”

This book provides lots of starting points for straight people seeking to take a more proactive role, or merely to better understand the gay people near them. It also will help gay people—especially youth—who are looking for a better support system than what they find in their communities. Most of Woog’s subjects—though not all—are active with local or national affiliates of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG). Others have affiliated with or founded more specialized groups and Web communities. Each essay ends with a resource listing and/or Web address for further information.

Reviewed by

Laurene Sorensen

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.