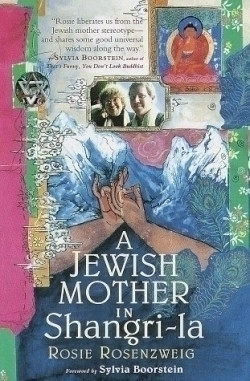

A Jewish Mother in Shangri-La

“I thought that if I practiced Judaism according to my heart, my children would follow… ,” Rosenzweig notes in her journal-like search, written with far more profundity than the flip title suggests. Flip because the “Jewish mother” imagery has a cartoonish portrayal. The real Rosie Rosenzweig is anything but a cartoon. She is any mother (and in this case, one with an extraordinary wide-ranging questioning mind) wondering why her son has strayed into unknown territory. That uncharted terrain is Shangri-La, an inner state of peace, a paradise of the mind apart from one’s geographically situated self. Her son has become a Buddhist and was on a three-year retreat away from his family. At the end of that time, it is Ben who suggests to his mother a journey to some of the habitats and gurus that have drawn him away, as she thinks, from his heritage and upbringing. She will find that Ben has not waived the legacy of generational history, but rather, he has added to his life a dimension of philosophical thought that he wants her to contemplate, understand, and, most of all, accept. His new direction is an expansion, not a disavowal, of his Jewish-nurtured childhood.

Leaving her psychotherapist-husband at home in Massachusetts, Rosie sets off with Ben for Plum Village, a Vietnamese Buddhist farm enclave in southern France, and Nepal. Rosie has been following strict orthodoxy rituals for the past four years, observing the Sabbath and following dietary laws. Ben assures her that the Plum Village enclave is strictly vegetarian, and in other places she can eat selectively. On the Sabbath, wherever she finds herself, she reads the Torah portions for that week. Mingling her thoughts with the Buddhist teachings that she is awakening to as the journey progresses, her quest always seeks similarities and connections between Buddhist and Jewish principles that could define a mutuality, a confirming of belief between mother and son.

As she journeys, Rosie questions meanings in unfamiliar surroundings and worries about her religious-based decision not to bow to idols (the images of Buddha are everywhere). The reader becomes aware that Rosie and her husband have been questioning-searching souls for several decades. They were brief followers of the hugging psychology hype of California in the 1960s, and moved into other New Age cloisteristic contemplation and varieties of meditative experience. On her Buddhist trip she is almost primitively aware of every detour from the norm of her life: observing overhanging sycamores, she wonders: “Could I do the same for my son? Could I allow him to naturally choose his own spiritual path without forcing him into the heritage of his ancestors? Or would this journey with him influence me to bend and bow as unnaturally as those poor trees over my head? After this journey with my son, what shape would my life take?”

There are private meetings with Ben’s gurus; involvement in Buddhist daily life of work and prayer at Plum Farm; the exoticism of Nepal. Rosie gains insight even as peace eludes her.

A year later, unable to invest her Judaic studies with the eclecticism attractive to her in Buddhism, she travels to Israel. “Somewhere in the length and breadth of that country, I hoped to find my own evidence for the prolonged study and practice of a genuine Jewish mysticism.” It becomes yet another search not unlike the many searchings of her past years. Nothing, thus far, can solace the wound “of what it means to feel that a child has strayed far from home.”

Rosenzweig continues Buddhist studies at her home in Massachusetts, comparing them to ancient Jewish teachings. Will “these disparate elements of my life (evolve) into one common denominator?” she wonders. Much of the book is her weighing of comparisons between Jewish and Buddhist texts. The thinking of rabbis of earlier times occasionally seems placed as compelling evidence of the relevance of ancient Jewish texts and Buddhist principles and their similar application to daily life.

Briefly Rosenzweig finds peace in an Israeli desert. Can she find that same peace in North American suburbia? When will her mind stop “shopping in the spiritual marketplace?” The book is provocative, rousing the reader in intimate fashion to personal thinking, pondering differences and connections with a non-stop quester … and questioner … Rosie Rosenzweig. (August)

Hannah Merker (Listening, 1994, Time Being Made of Moments, 1985) lives aboard the good ship Bette Anne in Sea Cliff, N.Y., writing articles, reviews, editorial work, two newspaper columns, and her forever-in-progress work, Waterborn (stories of her 19 years living afloat in the Northeast).

Reviewed by

Hannah Merker

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.