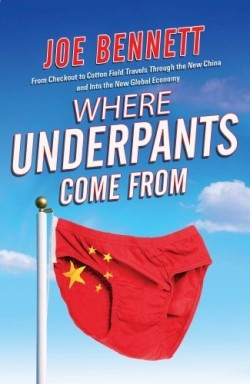

Where Underpants Come From

What do we know about China, the enormous nation that will most likely dominate the next century? Already most of us are clothed by China, shod by China, supplied with hardware by China, effectively in debt to China. And yet most of us know very little about China, the author writes. With this query in mind, and a new $2.99 pair of mens underpants in hand, Joe Bennett sets out to learn about world trade by finding the origins of his made-in-China knickers.

His journey begins with a series of emails to and from companies not all that willing to share information. He is successful, however, and soon we have landed in Shanghai. There, Bennett meets with manufacturers, visits factories, and wanders around town. His quest takes him by bus and train out to rural China, then to Thailand in an unsuccessful effort to find the rubber trees from which waistband elastic is made, and back to China. In the city of Urumqi, in Xinjiang Province, he encounters the land where Chinese rule and the indigenous Muslim population of Uighurs collide.

Often, the books ostensible purpose-mapping the path from the manufacture to the shipping of a pair of mens shorts-is merely a vehicle for Bennetts detailed descriptions of people and places. The chaotic traffic, the chess and spitting in the park, chopstick lessons in a restaurant-Bennett brings China to the page. No detail escapes his attention or his wry humor: In the communal dining room a much older woman squats in the corner like a refugee. She is shaving vegetables over a blue plastic bucket with a cleaver that would bring gasps from a jury.

As the book progresses, not one but three cultural gulfs emerge. The first is the vast lack of knowledge the average Westerner has about the Middle Kingdom and the resulting Chinese xenophobia. The second is no less sobering: the communication barriers between the average Joe and the huge corporations that dream up, order, manufacture, and transport all of our stuff. The third is the tension between the Uighurs of northwest China and the ruling Chinese.

This is a richly written book; Bennett threads his narrative through detailed description of his surroundings and concise, and at times, refreshingly frank accounts of Chinese history and political and economic development. He shows us heedless taxi drivers, giggling waitresses, and Swiss businessmen eager to make their fortunes. The history of Chinese writing, corruption, the odd gathering of expatriates, the mass migration of the Chinese out of rural provinces and into cities, and the pollution that hangs over everything-its all here.

By the time he gets to Bangkok, Bennett is tired. His mission foiled, he can only wander around the city, frustrated and aimless. But his continual reflection on the relationship between his comfortable life and what he is observing supports the narrative even through the occasional lapse in momentum. What does it mean, for example, that Winnie-the-Pooh has become an icon that is printed on toothbrushes? Perhaps the high (or low) point of this reflection comes when Bennett is photographed, at the request of his publisher, standing in a Xinjiang cotton field in his underpants.

I am standing in a field from which someone wrests a meager living. I have just dropped by in a plush car to be photographed here, to spend ten ridiculous minutes posing before leaving again with a cameraful of glib imagesÉimages designed to amuse and deceive. I am acutely aware of being superficial and parasitic.

An English-born resident of New Zealand and a travel writer, Bennett has published several collections of his travel columns. Where Underpants Come From was first published in the UK by Simon and Schuster.

By turns philosophical and hilarious, Bennett keeps moving toward a hopeful conclusion about the meaning of his experience: Everything I have ever heard or read about this country stressed its difference. But a few trivial merry minutes in a middle-of-the-road restaurant on a damp Wednesday evening in Shanghai have stressed its similarity. These people are peopleÉWhats more they are easy-going people, people who like to laugh and people who dont consider a restaurant meal to be an exercise in isolation, formality or social pretension.

While the Chinese have good reason to mistrust foreigners, Bennett believes that continued trade will continue to break down barriers between people. With Bennett as our guide, and with the benefit of his ability to map the humor and humanity of any situation, we are in good hands.

Reviewed by

Teresa Scollon

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.