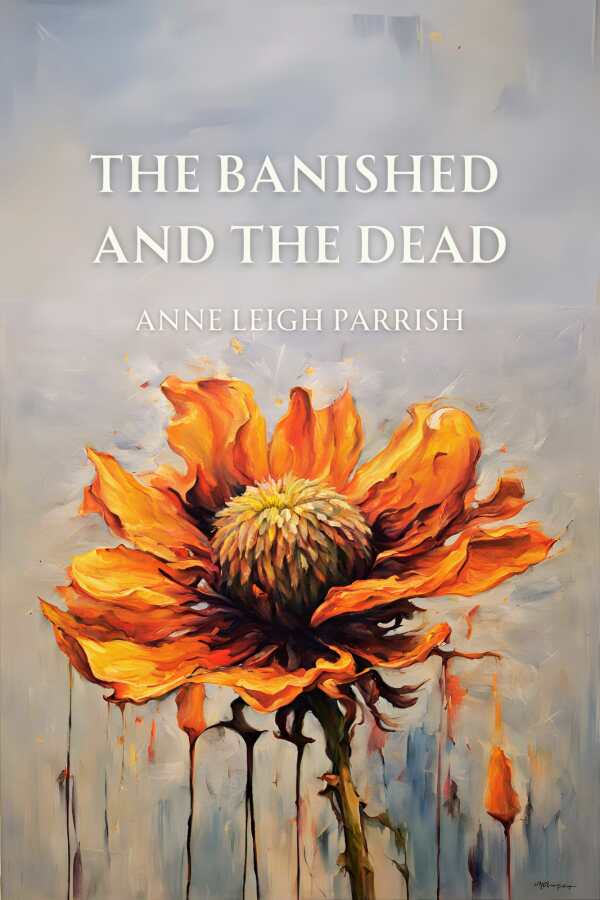

The Banished and the Dead

The vibrant poetry collection The Banished and the Dead is a stark, deliberate confrontation with the truths people choose to remember and the ones they struggle to name.

Anne Leigh Parrish’s vivid poetry collection The Banished and the Dead navigates themes of memory, personal relationships, and the instability of human emotions.

Taking the form of an emotional map, the book traces the uncertain boundaries between family legacies and personal identity. Its poems probe how memories define, obscure, and sometimes betray people. In “Trove,” emotional distance is established via a distant point of view; beneath the poem’s measured surface, shards of unresolved resentment pierce through. The second stanza, made up of three clipped lines, is a sharp flash of violent retribution: “All she wants is to stab her father in the heart.” The succinct tercet closes with a single, almost dismissive observation: “A mésalliance, you think.”

Here, as throughout the collection, the poems grant expression to the impulses a person is trained to suppress. Threatening to overrun the cultivated order of things, banished thoughts accumulate like invasive foliage in a neglected garden. Further, the poems make a space for what is often pruned away to bloom in full force.

Focusing on the unspoken tensions that saturate family life, much of the emotional material in the collection works to confront the inherited hurts that calcify across generations. Still, the poems do not seek personal reconciliation, nor to deliver moral instructions to others. Instead, the poems refuse the rhetoric of healing and dwell in the charged space between hope and despair, lending the work tensile strength. Indeed, here, emotional clarity doesn’t come from resolution, but in the willingness to confront what persists. It’s a sentiment that’s crystallized in the closing line of “Trove”: “Live with the sorrow you inherit.”

The poems make use of restrained syntax, with limpid diction and a stark economy of language. They are anchored in vibrant images and metaphors that broaden their emotional reach. Often, they turn to cyclical natural patterns to explore change, permanence, and the inevitability of loss. In “July,” the heavy stillness of midsummer becomes an emblem of a love fading by degrees. In “Almost April,” the return of light after a long darkness is cast as a paternal voice delivering somewhat terse counsel. Indeed, as the tone vacillates between comfort and rebuke, the anthropomorphized light serves as a stand-in for an absent authority figure, prompting the speaker to reconsider the past. Moving beyond the immediate experience of the poems’ speaker, these gestures point to broader existential questions about perception, time, and the stories people inherit.

Offering no absolution, the book portrays human emotions as dualistic: joy braided with sorrow, and clarity shadowed by doubt. A stark, deliberate confrontation with the truths people choose to remember and the ones people struggle to name, the poems collected in The Banished and the Dead highlight time’s indifference as an essential force in shaping human understandings of identity and legacy.

Reviewed by

Xenia Dunford

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.