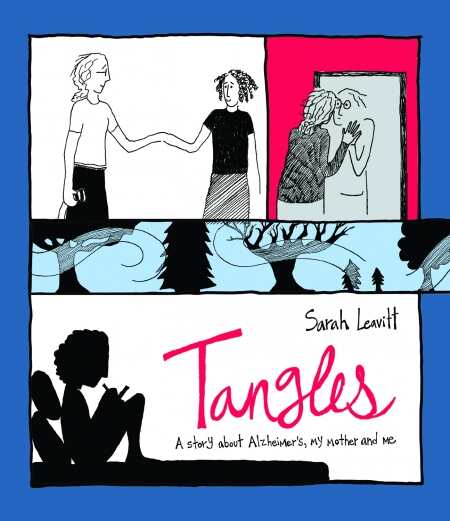

Tangles

A Story About Alzheimer's, My Mother, and Me

No diagnosis is as evil as Alzheimer’s. While it slowly strips away memories, experiences, and personalities, it leaves victims with enough awareness to know something is terribly, and terrifyingly, wrong. At some point, even this cognizance disappears for the victims, granting some measure of relief. But for family and friends witnessing the slow, inevitable destruction of a loved one, the reprieve comes only at the end.

In her powerful graphic memoir, Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me, Sarah Leavitt shares her family’s six-year journey as Alzheimer’s reduces the mother she knew and loved into someone unrecognizable.

Leavitt’s story depicts her and her family at their best and their worst. Visually, she creates a growing sense of isolation, loss, and distance through restrained usage of silhouettes and brilliantly placed stretches of white space. Like Mary Cassatt’s pastels of children, Leavitt draws her characters with expressive faces and amorphous abstractions for hands. As characters hug, arms connect at the wrist. Mother and daughter, wife and husband, sisters: family members’ bodies meld into each other even as one member is being taken away.

With something as terrible as Alzheimer’s, it’s almost impossible for the writer to communicate the extreme tragedy through words alone, and Leavitt uses the text to its full potential. She describes the pain as roles are reversed, as children find themselves forced to change a parent’s diaper. The rhythm of her words reflects the reduction of her relationship with her mother to a series of lists and chores. The litany of loss, ticking metronomically through each memory, becomes a march toward the inevitable destination to which not even the happiest flashback can alter the course.

When Leavitt illustrates her mother—a woman who “loved all of nature: plants, worms, rocks, soil”—expressionlessly stepping on a wasp, unfinished hands unconnected to each other, and grinding her foot back and forth until the insect is a black smear, readers feel how alien this woman with this disease has become to those who knew her.

The power of the graphic memoir resides not only in the reinforcement text and images provide each other, but in the juxtaposition of contradictory messages. This contrast keeps graphic novel aficionados returning to canonical images like those found in Art Spiegelman’s iconic series Maus. By portraying the Jews as the vermin the Nazi’s treated them as, Spiegelman simultaneously reinforces the humanity of his story even as his trope visually removes it.

While readers will find this contradiction in Tangles—the undrawn hands, for example, that show characters intimately connected even as the body part which connects them is not depicted—Leavitt prefers a less metaphorical approach.

Periodically, brief moments of lightness interrupt the family’s crucible. It’s hard to call these moments joyful, but they’re times shared by family members when the pain is lessened. In places, readers could almost fool themselves into believing everything will be okay, that there may be some miracle waiting on the next page.

Toward the end of her mother’s illness, to take one such moment, Leavitt and her sister share a bottle of wine and stories about the less distressing aspects of their mother’s behavior. “She wandered around the house all day, and when she banged into furniture she apologized politely,” Leavitt writes. “There was a grease mark on the mirror where she’d press her nose against it and talk to her reflection. It was so funny. We laughed and laughed.”

And while she writes laughter, Leavitt’s panel depicts tears falling down the sisters’ faces. By pairing the words of a lighter moment with the drawn complexities of grief, Leavitt shows the humor coming not at the expense of their mother but as a form of self-defense against the frustration and impotence caregivers experience while dealing with this vicious disease.

There is a lot of anger, pain, and honesty contained within these pages, and this book can be very hard to read. According to numbers released by the Alzheimer’s Association this year, nearly five and a half million Americans have Alzheimer’s and are cared for by fifteen million unpaid caregivers, mostly family. This book lets them know they are not alone. And in 2050, when forecasts predict up to sixteen million Americans with the disease, this book will be hailed as a seminal work detailing a universal experience.

Reviewed by

Joseph Thompson

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.