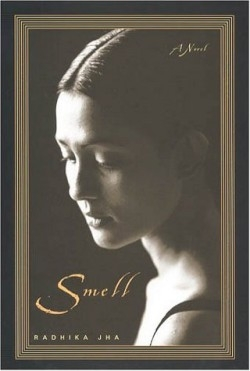

Smell

The India infusing this promising first novel is already a phantom, an

incense shrine to a secondary source. Its naïve narrator, Leela, knows her homeland only through the lush, imported spices sold in her parents’ Kenya shop. When her scholarly father is lynched, the uprooted family tree splinters twice more, as the mother and younger sons flee to hostile England, and Leela is impressed into drudgery at her uncle’s video-and-spice stall in Paris.

Her wrathful aunt—before throwing her out of their flat for good—gives her one bit of sage advice: spices must be well-matched, and, like all marriages, some grow sweet, some hopelessly bitter. Here begins Leela’s peripatetic sojourn in Paris, where she trusts the amorous kindness of strangers, guided only by her need to please and her hypersensitive sense of smell.

But Leela cannot live by the smell of baguettes alone, nor does Smell ever quite marry its two cultural influences. The Indian flavor, in the lovely opening, secedes to the Parisian, where social commentary dictates that her serial lovers be gustatory, artistic, self-regarding, amatory, and slightly anemic (that is, French—they predictably think of her as exotic erotic catnip). Her Paris is well described, but its characters’ (mostly) English dialogue sounds uniform, at a peculiar remove, which is regrettable, for the opening scenes of cultural claustrophobia with her Indian relatives has a strong interior life.

The more word-perfect Leela becomes in French, the more enervating, rather than erotically energizing, the plot becomes. She soon grows distressed at her own body’s smell, a miasma that—surprise—turns out to be a metaphor for the inauthentic self, or what Sartre once called “bad faith.” Certainly this is not Sartre’s physical revulsion at the viscous morass of a tree root in Nausea; her Paris does not teach metaphysics.

Unfortunately, the narrator’s self-awareness lags behind the reader’s and her resolution feels a bit abrupt, forced. Shortly after she creates a scene in a restaurant, sending the oysters back, having pronounced them “dead,” she decides to return to her latest lover, calling him that most treasured of words: home. Still, the root notes of desire, nostalgia, and appreciation of the beautiful are all here for Jha to command, forming a foundation for a ripening good novelist.

Reviewed by

Leeta Taylor

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.