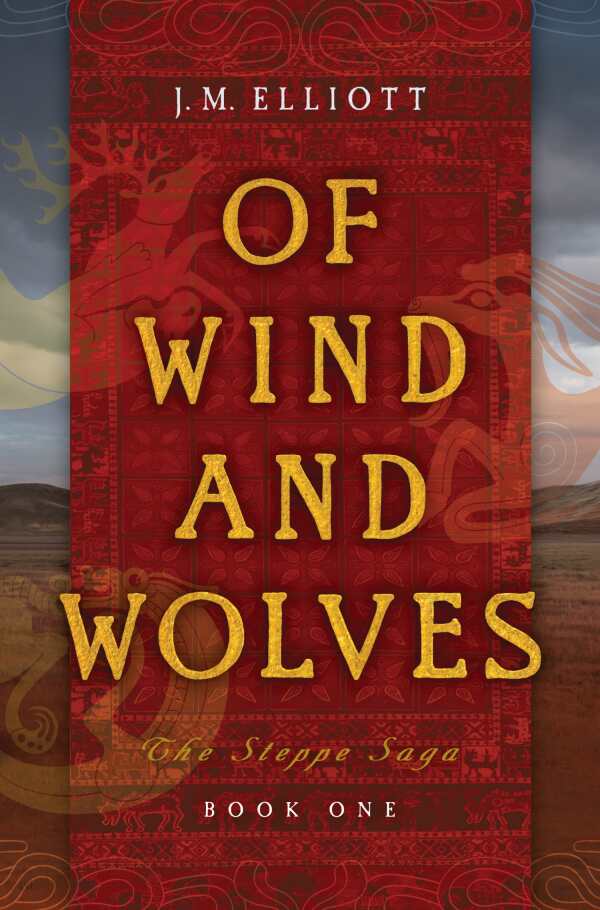

Of Wind and Wolves

Both violent and feeling, Of Wind and Wolves is an intricate historical novel about warfare and love.

Saturated with breathtaking cultural details, J. M. Elliott’s historical novel Of Wind and Wolves is a passionate, violent tale in which a young woman discovers what it means to fight for the tribes and customs she loves.

To save her tribe, Anaiti is betrothed to marry the aging Scythian king. First, however, she must take the scalp of an enemy. Though she was raised as a hamazon, a woman warrior, Anaiti is not seasoned in battle. To complete her mission, she is sent out with the warband, led by the king’s son, Aric. As she trains, Anaiti is drawn into a world of cultural clashes, politics, and bloodshed. She comes to love the warband’s way of life and resents the influence of the Hellenes.

The story is set in the steppe, an unforgiving land. Parts of the plain are barren; all of it poses danger. Here, all struggle to survive, reaping their keep from the land or moving from camp to camp. Yet it is not a desolate setting: Cool rivers flow, wild horses roam, and Anaiti—whose narration is enchanting, emotive, sharp, and poetic—describes the various landscapes in lush detail. The cultural and political tensions between the steppes’ various tribes are also explored in immaculate detail, with notes about articles of clothing, ancient gods, houses, and decorations, including nauseating skins made of tattooed human hide.

While Aric and Anaiti’s budding relationship propels the plot, their bond forged of mutual respect and longing, Anaiti’s personal growth and self-discovery are also centered. She remains deeply human in the midst of her heroism, and the couple’s tender moments stand in stark relief to the harsh background of the steppe, which also highlights people’s fragile humanity. The tribes fight each other to survive, and there are instances of rape, scalping, and capture. The gore of human sacrifices and bloody battles is juxtaposed to people’s soft, emotive sides: A kind seer, Erman, helps Anaiti understand her own divine powers; Anaiti learns to kill, but she also weeps, longs to be held, and is gentle with horses, whose goodness she remarks upon.

The contrast between routine violence and ordinary friendships and families raises uncomfortable but thought-provoking questions. Anaiti in particular wrestles with issues of honor, justice, and when death is preferable to life. In a scene following a decisive battle toward the story’s close, she reflects that she has reached a place of neutrality toward the bloodshed that her people’s way of life demands. She carries “neither the desire for peace nor vengeance” and accepts all that comes as “merely one more consequence.” The undercurrent of stoicism prepares Anaiti to face her fate in the book’s final pages, in which she stands on the cusp of a life she once tried to escape.

Extrapolating on Herodotus’s account of the Scythian people, Of Wind and Wolves is a historical novel of extraordinary complexity set against a harsh background of tribal warfare, love, and survival.

Reviewed by

Vivian Turnbull

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.