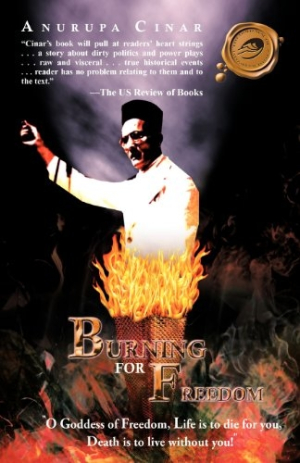

Burning for Freedom

“Wake up, O Hindus, wake up! … Let us pick up rifles and become soldiers worthy of defending our country,” exhorted Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a Brahmin Hindu yogi, poet, playwright, political prisoner, and founder of the secret Indian revolutionary society, Abhinav Bharat. His words stand in stark contrast to the pacifism advocated by fellow Indian freedom fighter Mohandas K. Gandhi, who battled the British Empire and fought discrimination against Indian minorities using satyagraha, a form of nonviolent resistance based upon “soul-force.”

Burning for Freedom, a historical novel, chronicles the life of Savarkar via the story of his fictitious bodyguard, Keshav “Keshu” Wadkar, during two periods. Part I (1913-1922) details the horrendous conditions endured by political prisoners in the British-run Cellular Jail, including Savarkar, who was incarcerated there for twenty-seven years. It sketches a portrait of the inmate as a kind teacher, stalwart leader, and patriotic reformer rather than the dangerous revolutionary many considered him to be. Part II (1938-1948) describes Savarkar’s political activism following his release from Cellular Jail, and contrasts his firebrand methods with Gandhi’s satyagraha.

Author Anurupa Cinar pays unabashed homage to Savarkar. He worked tirelessly to unite what he called “Hindustan” under Hindu leadership and advocated for abolition of India’s harsh caste system. Yet Savarkar also believed that “absolute nonviolence is absolutely sinful” and is “the very negation” of the Hindu sacred text, the Bhagavad Gita.

The book also casts aspersions on Mahatma Gandhi, describing his political advocacy as “shenanigans.” The author’s characters chastise Gandhi and the Indian National Congress for creating a “political milieu of Muslim appeasement.” Cinar’s Savarkar asserts that eating from a Muslim’s hand is irredeemable blasphemy, and warns Keshu not to fall for the tricks of the “wicked Muslim warders” who will employ deplorable measures to convert him—and everyone else—to Islam.

Cinar’s thorough research is commendable, and Burning for Freedom is often a gripping tale. However, it also is flawed. “All facts, incidents, and situations in this novel … are true and documented,” says Cinar. Yet, five pages of author’s notes contradict that assertion, repeatedly describing places the text is fictionalized, imaginary, or even inaccurate. In addition, the book sometimes reads like a novel, but at other times comes across as either a documentary or a partisan political advertisement.

Perhaps most seriously, Cinar’s passion for her subject and her sensationalistic writing style detract from the telling of Savarkar’s stark life story. Page one alone contains two italicized words and nine exclamation points. In other places, Cinar describes horrific circumstances and then concludes, for example, “It was a pitiable situation,” or “It was being very painfully drilled into his head that he had to be a mild cow.” The narrative would have been more compelling had Cinar trusted readers to grasp the gravity of her characters’ circumstances without stating the obvious.

These shortcomings aside, Burning for Freedom meticulously describes the life of a remarkable person and offers an alternate view of history that is both startling and worthy of consideration. Readers must decide for themselves whether Cinar’s descriptions paint a more realistic picture than do current texts, or whether her account constitutes revisionist history.

Reviewed by

Nancy Walker

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.