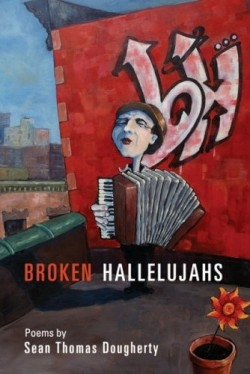

Broken Hallelujahs

In his 2002/2003 Frost Medal acceptance speech, Lawrence Ferlinghetti described three types of poetry, the last and most important being standing poetry, “the poetry of commitment, often great, often dreadful.” Sean Thomas Dougherty is a standing poet. He tackles socially aware subjects and draws his inspiration, not from the literary canon, but from music and spoken word. In his latest collection, Broken Hallelujahs, Dougherty demonstrates that he is a master of momentum. He does not pause to catch his breath and thus catches his readers right along with him. The opening poem, “The Sentence,” announces the poet’s belief in the power of language: “The sentence is a chanteuse, unretired, stirring with a strong sigh, a suffering sparrow, outside a gray downtown Nativity scene, this last sentence: a small, winged thing rising—” The sentence, the poem, flies off the page. It is not a trick, but rather language’s possibility to change and perhaps to promote change.

Broken Hallelujahs is the 104th book to be published in BOA Editions’ American Poets Continuum Series. Despite the distinguished company he joins, Dougherty seems to prefer musicians to poets, for example, Biggie Smalls and Leonard Cohen to Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell. In “Call Out,” he asks, “Who donned Robert Lowell’s glasses and forgot how to shake one’s assets?” It is an ironic question considering the similarities between Broken Hallelujahs and Lowell’s Life Studies. (Most notably, both collections are interrupted by a family narrative in prose, Dougherty’s “The Dark Soul of the Accordion” and Lowell’s “91 Revere Street.”) And it is here that the major contradiction of Dougherty’s collection lies. Broken Hallelujahs vacillates between high and low art, using graffiti and arias in the same moment. In “Canzone Sprayed with Graffiti,” Dougherty describes a street dancer as “Giotto reaching for an angel’s halo.” Although the result of this technique can sometimes be bewildering, the point is clear: Giotto and the boy are equal artists.

Like Ferlinghetti and other writers of the Beat movement, Dougherty is a poet of the people. He expands the meaning of “Beat Poetry” to include not only the “beaten down” but also “the beat,” i.e. rhythm. His interest in rhythm is apparent in the measured forms he often uses and in the names he mentions: Marvin Gaye, Thelonious Monk, Satchmo. When he includes family narratives, such as in “The Dark Soul of the Accordion” and other prose pieces, the intersection of his two beats (the oppressed and the musical) becomes clear. Although this combination might be surprising from another writer, it is appropriate for Dougherty whose performances and experimental writings are internationally renowned.

Reviewed by

Erica Wright

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.