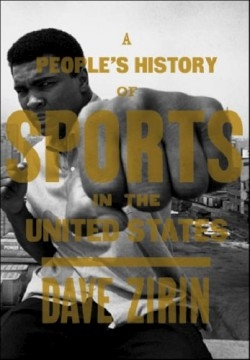

A People's History of Sports in The United States

For David Zirin, the unexamined sports life is not worth living. While other writers might be content to browse over box scores or dish the dirt on the private lives of athletes, he prefers to look deeper into how the games address (or not) a wider array of social issues.

The book is a straightforward examination of how sports gradually changed from a waste of time that detracted from serious work (and prayer) in the days of the founding fathers, to a way to provide diversion from unrelenting industrial labor, to a multi-billion dollar enterprise today, not only on the fields of play, but in merchandising as well.

Zirin notes the imprimaturs from presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, who promoted athletics as endemic to the American spirit, as well as to keeping a sound body and mind. Where Zirin says “America,” though, he is really writing about the shame of not living up to democratic ideals by excluding women and African-Americans from meaningful participation; for some reason, other ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the book for the most part. All this is prelude, however, until we arrive at the World War II era. It is at this point—in the form of Jackie Robinson’s breaking of baseball’s infamous color line—that A People’s History really takes off.

America moved into a desegregationist mindset following the War. African-Americans would no longer accept being treated as second class citizens and sports was seen as one way to prove their equality, if not superiority. Robinson led the way for others such as basketball’s Bill Russell and football’s Jim Brown to make statements on and off the court.

Zirin uses the 1960s and the civil rights movement for his largest narrative, and in particular the effect Muhammad Ali—one of Zirin’s favorite subjects—had on America. Ali was at the peak of his career when he refused to be inducted into the military. The fallout propelled him into the national and international spotlight as a man of principle who would rather lose his fortune and go to jail than fight in a war he considered immoral. This segues into other protest movements, including the 1968 Olympics where Tommy Smith and John Carlos raised gloved hands in a “Black Power” salute during the playing of the U.S. national anthem.

Unfortunately, Zirin then seems to be in a rush to bring his book to a conclusion. One quibble in a book of this nature is that it’s simply too short. The struggle by the women’s movement gets relatively little accounting, save for a brief passing of Title IX and a few key figures such as Althea Gibson, Babe Didrikson, Billy Jean King, and Martina Navratilova. Other topics (drug usage, strikes, even Curt Flood, who opened the door—for better or worse—to widespread free agency) merit relatively brief mention; perhaps this will serve to goad interested readers into further investigation.

Reviewed by

Ron Kaplan

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.