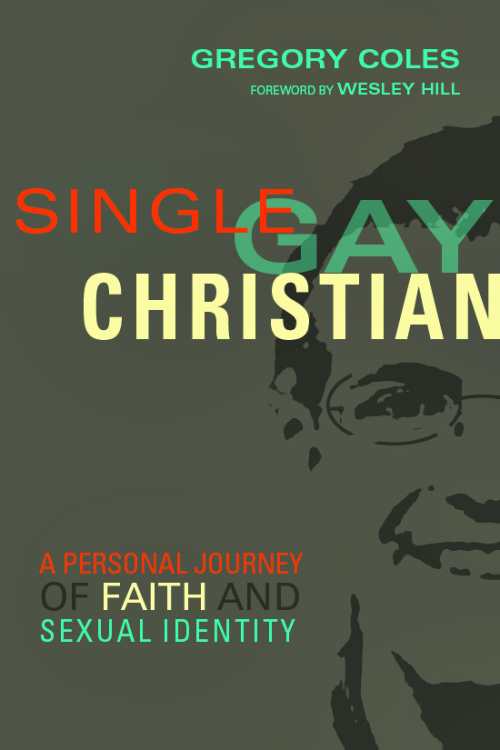

Single, Gay, and Christian

Gregory Coles grew up knowing that he was gay—and knowing that his identity was something that some Christians would not accept. Still, from a young age he remained introspective, active in church circles, and absolutely committed to his faith, all of which led him to explore what Christian life might mean for someone who was both certain of their identity and secure in it, and convinced of the truth of the gospels.

His complex, personal answer—which involves celibacy–comes through his exploratory and lovely new work, Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity (InterVarsity Press). The conclusions he arrives at are neither simple nor prescriptive, and his intimate theological disclosures are certain to move inquisitive readers from all religious perspectives. We spoke to Gregory about his brave new book—necessarily at length.

Gregory Coles, author of Single, Gay, Christian

How should liberal allies respond to your story in a way that doesn’t discount your choices?

Gregory Coles: 'I don't want to tell everyone's story, but I do want to be able to tell my own.'

I think one of the most important things I’ve learned in my own conversations with other folks who identify as LGBTQ is that we’re not all alike, nor are we necessarily trying to be. Characterizing everyone within a minority group as identical is, as I say in the book, a way of colonizing them and denying them their right to be uniquely human.

So I hope that open and affirming LGBTQ allies will be open to recognizing that there might also be people like me–people who long for their love and support as allies but who might not fit into the most familiar narratives of LGBTQ experience. I don’t want to tell everyone’s story, but I do want to be able to tell my own.

You talk about LGBTQ equality being kind of a litmus test issue for evangelical communities; it is for liberal communities, too, but in the opposite way. I can almost see your book serving as a bridge.

That work of reconciliation and opening up conversation that you’re describing–that’s certainly some of the work I hope the book will accomplish! One of the reasons I’m reluctant to wear a label like “liberal” or “conservative” for my Christian faith (and a reason I think many other millennials are likewise reluctant) is that it seems to commit us to some form or another of “toeing the party line” instead of a primary commitment to pursuing love and honesty and depth in our faith.

The question I want to be constantly inviting any self-identifying Christian (whether “liberal” or “conservative”) to ask is this: am I loving Jesus with my whole heart, and loving my neighbor with that same love? I suspect folks on both sides of the liberal-conservative divide will disagree with some of the answers I’ve reached about what it means to love God and others well—but I hope folks on both sides of that divide can at least agree to enter into a dialogue around these questions.

“Obedience is supposed to be costly” was a line/paragraph that really stuck with me. Do you think that that notion is something that evangelical traditions understand more clearly?

I think that evangelical and mainline traditions tend to recognize and pursue different aspects of costliness. Mainline traditions have a much better track record (in my view) of taking costly stances when it comes to systemic matters of justice and social equity, whereas evangelical traditions tend to emphasize personal costliness over the societal.

In calling people to costly discipleship, then, I’m not really trying to be pro-evangelical or pro-mainline. I want to ask everybody (including myself) to consider whether they might need to start acting more pro-Jesus in their pursuit of a costly faith.

Your work is theological and personal; you show yourself taking ministerial roles, whether on a walk with friends or in church communities, throughout the book. Do you see that as one of your callings?

I’m in grad school pursuing a PhD in English, with a concentration in rhetoric and composition. And that obsession I have with language comes up in the book a bit as well, I think. But being “in ministry” in various ways has always been part of my story, and I suspect that it always will be, regardless of where my paychecks are coming from. Certainly, following Jesus and wanting to walk with others along that journey is always going to be a big part of my life!

Your handling of the Bible, and of certain biblical verses, moves between being exegetical and literal. How would you describe your approach?

Whenever I approach the biblical texts (or, really, any texts), my primary hermeneutic question is this: How does this text ask to be read? To the degree that a lens of readership seems assumed or constructed by the author, what is that lens, and how can I do my best to adopt it in my own reading? I’m very nervous about a hermeneutic of “biblical literalism,” because it seems to me that some of the biblical texts aren’t asking to be read literally, and our insistence on reading them that way without their permission is a kind of textual violence.

But in cases where the text does seem to invite and expect a literal reading, I want to do my best to follow that reading, to take the Bible where the Bible asks me to take it. As always, there can (and will) be sincere disagreement about where the Bible is asking to be taken–but I’d rather have that intellectually honest disagreement than be committed to an unconsidered literalism at all times.

Were you taught to read the Bible the way you’re describing, or is that a lens you developed on your own?

Growing up, I had a lot of theological discussions around the dinner table with my family. My dad is seminary-educated and a former pastor, but he and my mom were unlike the stereotypical “Christian parents” in the sense that they were always more interested in equipping us to study the Bible and answer questions for ourselves than they were in making sure that we agreed with them on every theological issue.

So I grew up with a very high regard for the Bible, but not always with a high regard for the ways the Bible was being interpreted by people. (And by the age of twelve or so, I could have already told you places where my theology differed a bit from my parents’ theology.) The hermeneutic that I learned from my parents and honed during those dinner table chats has been refined a bit by my academic study of rhetoric, but the heart remains much the same.

Why stay evangelical?

I hope that I’ll always be much more committed to following Jesus than I am to any denominational ties. Honestly, I find that the word “evangelical” can communicate some very true things about my practice of faith and my theology when I use it to describe myself, but it also communicates some very false things to some of the people who hear it.

I’ve never been part of a local congregation where I agreed with the pastoral staff or with my fellow congregants about everything, and I’m confident I never will. (As one of my former pastors used to say, “If you find the perfect church, don’t join it–you’ll ruin it.”) So if I someday find myself living in a community where it seems like my best opportunities to serve and follow Jesus can be found in a congregation that doesn’t use the “evangelical” label, that won’t rock my world too much.

You reference yourself as still closeted, though it seems natural that the book itself will complicate that. Are you planning a book tour? If so: at what kind of venues?

I didn’t actually decide to come out of the closet until I signed the book contract; before that, it was just an open question I was asking myself. I officially “came out” to the world two months ago, by posting an Amazon link to my book on Facebook.

Now that I’m out, I have begun to get a few speaking offers, and I’m mostly saying yes (because that’s what first-time authors do!). So far, these have mostly been predominantly conservative venues that recognize they’ve done a poor job of loving the LGBTQ community and want to begin a conversation about how to do better. This is a conversation I’m pretty passionate about advancing–so chances are good that, as long as people keep asking me to talk about it, I’ll keep saying yes.

Your book fills a major gap in religious publishing. But I would imagine that also puts an emotional burden on you, as someone who’s going to be presenting a perspective that people have learned to ready a response for, rather than just hear and absorb. How are you handling self care, and how can your coming audiences make that less heavy on you?

I won’t lie, that burden has felt pretty heavy sometimes. I’ve had nights of lying in a curled-up ball on my bed, whispering prayers as tears trickle out the corner of one eye, and I’ve sent my current pastor a lot of angsty emails at one in the morning. But I’m continuing to find that Jesus is so gracious about walking with us through seasons that feel irrationally difficult, and I’ve had a lot of dear friends walking faithfully alongside me as well. (Friends like my pastor, who still reads and responds to my angsty late-night emails, God bless him.)

I hope and pray that the folks who read this book and disagree with me (on either side of the theological aisle) will continue to see me as someone who is committed to loving Jesus and to loving them well. As long as they can see that love in me (and perhaps begin to see it in one another as well), then I’ve got no regrets.

Are you concerned about the response you’re going to get from the left—that people will try to “fix” you with, say, matchmaking? And what might you say to someone who has those well-meaning, but obviously unsolicited and unwanted, impulses?

I never want to be ungrateful for people who desire to show love to me, however unhelpful their expressions of love may feel sometimes. Since I’ve come out, I’ve had people inviting me to ex-gay ministries, and I’ve had people telling me that they’ll be praying I get a boyfriend soon.

I don’t resent any of these people–I’m really glad that they love me and are trying to express that love in the best way that they know how. But I do hope that some folks on both sides of the issue might be willing to be silent and listen to me long enough to learn how they can love me even better, in a way that will feel more like love to me. And I’m not shy about inviting people into that learning process!

Who’s your ideal audience, and what do you want them to hear most from your story?

I wrote the book imagining that I was talking to my fellow Christian millennials, all over the spectra of theology and sexuality. But I also hope that it will speak to folks far beyond that group: church leaders, any LGBTQ folks, their family and friends, and anyone longing to have this conversation better.

Most of all, I hope that these readers take away two things: that being gay in no way disqualifies us from following Jesus; and that if Jesus is real and true and worth following, then he must be worth giving up everything for. If people wind up agreeing with me about theology and sexuality, that’s cool, but that’s not my primary goal.

Are you sure you’re not going to go the seminary route?

If I still more energy left after I finish the PhD, seminary is definitely next on my wish list!

What’s next for you?

I’m planning to write a dissertation! (And maybe a second book.) (And beyond that, God only knows!)

Michelle Anne Schingler is the managing editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler