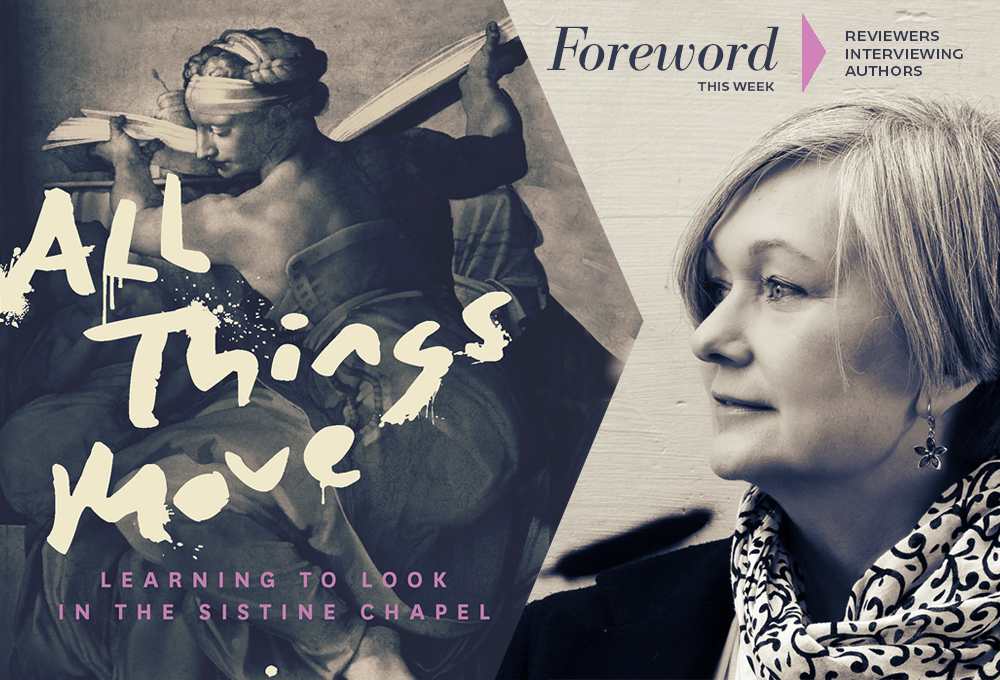

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Jeannie Marshall, Author of All Things Move: Learning to Look in the Sistine Chapel

No, you can’t step in the same river twice and no, the same painting will not be seen in the same way by different people. Just saming.

And also picking up on Jeannie Marshall’s point in today’s interview. Not only do we all take meaning from art in different ways, but we “also bring meaning to it.” She came to that realization when she found herself in an empty Sistine Chapel and found it to be a bit depressing—as if, art needs us as much as we need art. It’s an interesting thought experiment. See what your mates think at happy hour this afternoon.

In the meantime, check out Meg Nola’s Foreword review of Jeannie’s All Things Move, and then, enjoy the interview.

In the book, you recall how a priest at the Sistine Chapel politely asked a visitor to stop taking photographs. She seemed perplexed by his request, even after he reminded her that “this is a holy place.” There are also “shushers” on staff who urge people not to talk loudly or sit on the floor. Generally, throngs of tourists make their way through the site—with or without the appropriate reverence—but this was all different during the Covid pandemic. What was your experience then?

It’s not unusual for people to feel a little exhausted by the time they have made their way through the crowds and into the Sistine Chapel. I visited in the first few days of June in 2020 just after Italy started to open up after the first, extremely restrictive lock down. There were no tourists in Rome, which was not as wonderful as it sounds. It felt empty, and I realized on my way to the Vatican museums that the city was a little sad. The whole world was still in shock over what had happened. When I arrived at the museum, there was a sense that something special was happening. This was a moment when we would be able to visit the chapel without crowds but also see it with people who live in the city, maybe even see it with a different feeling for what is important in life.

I started listening to people and realized that I was one of very few non-Italians. When I entered the room, there were only a few people there, maybe a dozen. The guards were smiling, when usually they are a little tense. Many of the people who work there do so because they love the artwork. They knew it was unusual to be there when it was so quiet and I think they were pleased to see other people coming in and being able to just be in the room, to walk around without falling over someone. I thought about the room being left empty while we were all locked in our houses and it made me think about the way that we take meaning from the artwork but we also bring meaning to it.

You describe the 1527 Sack of Rome in vivid and terrifying detail. Martin Luther didn’t condone the violence, but his “words and thoughts were understood to give licence” to the “Christian soldiers” who brutalized the city. They killed children in orphanages, hospital patients, and the Vatican Swiss Guard. They also murdered priests, raped nuns, and slaughtered those “who sought sanctuary inside the unfinished Saint Peter’s.” Luther had justly criticized the corruption of the Catholic Church, but among the Sack armies, was there a deeper rage against Rome and Romans, along with the artistic and intellectual progress of the Renaissance?

From what I’ve read, it sounds as though people in Rome, including those in the church, did not really understand the anger of people who were further away from the centre of Catholicism. There was the obvious corruption going on with the way that indulgences were being sold in the periphery of Christendom to fund the church, but also Martin Luther was questioning the role of the Pope. Luther wanted people to come directly to scripture instead of having it mediated through the Pope. That was a challenge to the very structure of Catholicism. The soldiers were mercenaries and were, obviously, violent people on a violent mission, but the fact that they invoked Luther’s name and even went after the Pope and ransacked the churches to me suggests a deeper anger that goes beyond the money and wealth and opulence. It’s the anger of being lied to and of being disrespected, and we shouldn’t underestimate the deep fury that comes from feeling so thoroughly disregarded. The 1527 sack of Rome is not just one thing, but that element of indignation was a part of it.

Michelangelo wasn’t in Rome during the 1527 sack, but he returned to begin work on The Last Judgement in 1535. How had the city changed during that time?

Rome would have been far less populated by 1535 after the murderous rampage but also after the plague. There was quite a lot of physical destruction that happened as well so it would have looked different, too. But the Protestant challenge was also having an effect, so that people who still called themselves Catholic did worry that perhaps they had not been good Christians. The Last Judgement reaffirms certain Catholic doctrine, such as praying for salvation. And it still demonstrates an interest in connecting Christ to the past by showing him looking like Apollo, but it also shows that there were now more questions and concerns about what made a good Christian. I think there was more humility in Rome, maybe even a recognition that people are just people and the realm of God and the spiritual could not be fully known.

You’ve lived in Italy for a while now, and the book includes compelling glimpses of modern-day Rome—a city which you note bears an “enormous weight of significance and looks exhausted by its burden.” How do Romans feel about the Sistine Chapel? Do they visit often?

I’ve never looked at the statistics, so I don’t know how many visitors are Italian. I know that school groups go because I’ve seen them there. I saw a group of grade 3 students on one of my first visits. Their teacher kept them focused by giving them a list of things to find in the frescoes. They had to find the ark, and find Jonah, etc. I thought she should hand out that list to everyone in the room.

I think there’s a sense of pride that this globally acknowledged masterpiece is part of the country’s artistic heritage. But I think the crowds are a deterrent. Most Italians I know can name the parts of the ceiling, they know the sibyls from the prophets and know what’s in the central panels. I think that’s because they study art history at school and there is a sense of national pride. Catholicism spread and I feel connected to the art work partly because of the religion, but the people at the bar who make my cappuccino in the morning feel that Michelangelo is one of theirs, an Italian.

Have you visited the Sistine Chapel since you finished All Things Move? What would be your best advice to someone approaching the imposing vastness of the site for the first time?

I last visited the Sistine Chapel in February. I wanted to make one last visit before the book would be published and the winter is usually a quieter time. I was surprised to find that I’m still having new reactions to it. I see more in it with each visit.

I would recommend reading a little about the Sistine Chapel frescoes before visiting because it will help. Also look up some of the images online. The Vatican Museum has a nice website where you can see details of most of the ceiling. When you enter the room for the first time, it’s useful to look for one thing. Maybe start with the central panels or find the Libyan sibyl. Even if you only look at one part of the ceiling, you will have seen something. And, keep an eye on the benches that line the walls. If you can sit down it is so much easier to look up and take a few minutes to notice how intricate it all is and how it has separate parts but they are all worked into one very big story.

Are you working on any new projects?

I loved writing this book so much. I would open my laptop in the morning and go through my notes and write every morning, and it was such a pleasure. I am always, always writing, but writing this book was like nothing else I’ve ever done. Maybe that’s because it was partly a quest; I was trying to understand the art and also myself, so that in the writing I was also discovering.

When I finished, I immediately started work on something else that felt just as urgent, or irrepressible, perhaps. It’s a continuation of some of the themes that came up in All Things Move but it is quite different. I always find it hard to talk about work in progress because it’s not yet settled, so I won’t say more.

Meg Nola