Hillary's Back, But We Recommend These Indie Books on Other Women Who Broke the Mold

What Happened, Hillary Clinton’s memoir, has just been released. Clinton’s presidential nomination was a first, but she’s not alone in her ambition; other women have also paved the way as daring, determined rule breakers. These six books we’ve reviewed show other women who have broken the mold.

Standing My Ground

Memoir of a Woman Physician

Clair M. Callan

ArchwayPublishing

Softcover $15.99 (214pp)

978-1-4808-0807-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

This is the incredible true story of a remarkable woman who cracked the glass ceiling of the medical world.

Like many unsung heroes of women’s history, Clair M. Callan has had a remarkable career. Born in Ireland during World War II, she followed her mother’s footsteps into medicine, becoming an anesthesiologist. As her family grew and moved across continents, Callan balanced her work with her family, children, and eventual diagnosis of breast cancer, all during a time when women were not necessarily a welcome presence in the medical world. She describes her life and livelihood in the engaging memoir, Standing My Ground.

The book doesn’t avoid discussing the difficulties that Callan experienced due to her gender, but it does treat them as a known entity, an occupational hazard that the author is fairly well prepared to handle. She approaches hostile bosses and a demanding home life with equal aplomb and a matter-of-fact resourcefulness born of both hard work and self-respect. This memoir may inspire women in particular, who still struggle for equal visibility in the sciences, but any medical professional will be able to take a page from Callan’s book. Rather than labeling herself a feminist, mother, or icon, she simply commits herself to being the best possible professional, and her memoir is all the more accessible for it.

In fact, with its clear-cut style and thoroughness, this book could serve as a manual for success in medicine. From medical-school experiences to research in the private sector, the author’s career track takes her through several different areas of the medical world, and explores the connections between them. The book particularly emphasizes the importance of participation in professional organizations and the development of personal networks. Callan spells out several strategies for working into useful leadership positions, and demonstrates why taking on new roles is critical to professional advancement. Leadership tips feature prominently, and the book often highlights the importance of shedding the early socialization that encourages women to defer to men in professional settings.

Though it chiefly describes her medical career, the book also demonstrates an impressive example of the elusive healthy work-life balance. Callan often cites her own mother’s regular absence from the dinner table as inspiration for her family-oriented attitude. Yet she and her husband function as equals professionally, and though she occasionally makes sacrifices for her family, the presence of her children doesn’t prevent her from succeeding in her field. Her even-keeled management of both her medical and maternal roles will resonate with career women of all stripes.

Though Standing My Ground is likely to appeal to career women, medical professionals in general will find this memoir’s many tips and pointers to be useful. Callan’s years of experience are not only a good representation of a woman’s medical career during a time of social transition, but are also a fine overview of the real requirements of success in medicine.

ANNA CALL (May 19, 2015)

Rachel Carson and Her Sisters

Extraordinary Women Who Have Shaped America’s Environment

Robert K. Musil

Rutgers University Press

Hardcover $26.95 (288pp)

978-0-8135-6242-1

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Environmentalism and feminism are two passions igniting this rich biographical study of American women in science.

In Rachel Carson and Her Sisters, Robert K. Musil uses the life and writings of Rachel Carson, particularly Silent Spring, as an exemplar of women’s participation in the American environmental movement. He places Carson’s achievements in context by illuminating, through dense but intriguing essays, the lives of trailblazing female scientists who inspired her and for whom she, in turn, paved the way. Fueled by imagination and humanitarian conviction, these conservationists entered into political activism in spite of the media, industry attacks, and overall gender bias that hindered their academic advancement.

Although Silent Spring was likened in revolutionary effect to Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, earning Carson the designation of “the little lady who started it all,” she in fact drew on the work of many scientist foremothers from the previous century. Among these were Susan Fenimore Cooper (daughter of novelist James), whose wildlife chronicle, Rural Hours, made her the first “literary ornithologist,” and chemist Ellen Swallow Richards, the first MIT-educated woman, whose fervent advocacy of food standards and water quality earned her the title “the first lady of science.” It is just as enlightening to trace Carson’s direct influence on a subsequent generation of women scientists, including cancer survivor Terry Tempest Williams, who has carried the fight for environmental health and human dignity from prairie dog colonies to a Rwandan genocide memorial, and Devra Davis, who broke the silence about chemical pollution in Pennsylvania’s steelmaking region.

Musil, who teaches environmental politics at American University, is also the author of Hope for a Heated Planet. The mini-biographies here are extremely well researched, though they occasionally go into an unnecessary level of detail. When discussing Carson or Williams, the author’s adulatory tone can approach hagiography. Moreover, each chapter reads like a stand-alone thematic essay, which entails some repetition. However, Musil successfully pitches the work to laymen with no special scientific background; his clear, methodical prose obviates the need for the opening caveat: “A quick caution. There is science inside these pages.”

Like Martin Luther King Jr. was for the civil rights movement, Carson was, according to Musil, “the visible peak of a whole range of women who came before her and who carry on today.” Carson died of breast cancer at fifty-six; there was much more she might have accomplished, but this inspiring group biography suggests that the healthy world she and her predecessors envisioned is coming closer to fruition.

REBECCA FOSTER (May 27, 2014)

Wall Street Women

Melissa S. Fisher

Duke University Press

Softcover $22.95 (215pp)

978-0-8223-5345-4

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In a well-researched and enlightening account, Fisher traces the rise of the first generation of women on Wall Street to reach senior level positions previously held solely by men.

A small group of women interviewed reflect on their own individual experiences. Citing a lack of attention to this group by researchers, Fisher, a visiting scholar at New York University’s Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, first interviewed the women for her dissertation research in the mid-1990s and followed up with them as recently as November of 2010.

The book will be of interest to researchers working on issues related to feminism and women’s studies, as well as to Wall Street historians. Ethnographers in all fields can also benefit from Fisher’s approach, which consists of a combination of individual interviews, observation of and participation in association meetings where the women networked, and a final group discussion.

Using newspaper articles and op-ed pieces, Fisher also relates the women’s individual experiences to broader historical and cultural events. While the women (identified only through pseudonyms) entered the financial industry in the 1960s and 1970s—a time when lawsuits brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commissions addressed sexual discrimination of women in the workplace—Fisher emphasizes how they viewed Wall Street as a meritocracy, and even when faced with discrimination, they believed their hard work would be rewarded. As a result, they focused on developing their skills by learning on the job, and, for some, attending business school at night while continuing to work in financial firms during the day.

Even though the women perceived their path to success as depending on individual ability and responsibility, a major theme throughout the book is the important role networking also played in the women’s careers. Fisher specifically seeks to dispel the myth of “the lone female pioneer.” At meetings of the Financial Women’s Association of New York and the Women’s Campaign Fund, the women often found the mentors who didn’t exist in their workplaces.

Although the first generation of women to work on Wall Street found friendship and support among their female peers, they discuss how they were dismayed to see the next generation of Wall Street women demonstrate a strong sense of entitlement and lack of dedication to the firms they worked for and their clients. Fisher explores how it sometimes created tension between the groups, rather than solidarity.

In this compelling, detailed account, Fisher identifies the challenges the women faced as they strived to succeed in a male-dominated industry. She also presents their hopes for their own futures, as well as for future generations of Wall Street women.

MARIA SIANO (August 30, 2012)

The Women Who Broke All The Rules

How the Choices of a Generation Changed Our Lives

Joan P. Avis

Susan B. Evans

Sourcebooks

Unknown $18.95 (229pp)

978-1-57071-430-6

Buy: Amazon

American women born between 1945 and 1955 came of age during a unique historical period. These women, raised with the traditional expectations of college, marriage and motherhood, reached adolescence during a time of enormous social change. How did this transitional generation negotiate unheard of freedoms and choices for women that most women now take for granted?

Evans, an authority in survey research methods, and Avis, a psychologist, call the women of this generation “torchbearers.” One hundred women born between 1945 and 1955 who had been continuously in the workforce since completing their education were interviewed. The research questionnaire included a chronological life history survey; a series of questions allowing each woman to consider her role as a pioneer in the women’s movement (whether she used that label or not); how she reconciled her fifties childhood with her adult self; and the role of men and families in her life.

The result is a very engaging social history of ordinary women with extraordinary stories. Diane, a marketing director for a large computer company, talks about the conflict between her childhood training and her current life: “I grew up in the purest, most unadulterated structure—a Catholic female upbringing. I remember going to politeness classes where they taught us how to eat potato chips with a spoon. I was conditioned for a life which I am not living.”

Interestingly, while these women are very accomplished and lead noteworthy lives, few acknowledge their own agency and power in creating these lives. The authors note that many of the women erroneously ascribed their accomplishments to good fortune rather than to risk taking any direct action; they note that “eschewing credit for one’s accomplishments seems to be a generation trait for those who grew up as 1950s ‘good girls.’”

Of interest is the appendix, which contains the interview questionnaire, which readers can take themselves, or use to interview their female friends and relatives. Also rewarding is a segment on advice for younger women. Although the book is almost exclusively a social history of white, middle-class American women, it does include a few stories from African-American, Asian-American, and Latino women. Specifically tailored for a general audience, the book would benefit a sociology or women’s studies course, or provide the foundation for an oral history project. The authors conclude: “We encourage Torchbearers to accept that they are trailblazers who deserve credit for their individual and generational achievements. They are members of a lucky generation, but it was not luck that brought them to where they are today…Remember that the only thing permanent is change.”

REBECCA MAKSEL (February 13, 1999)

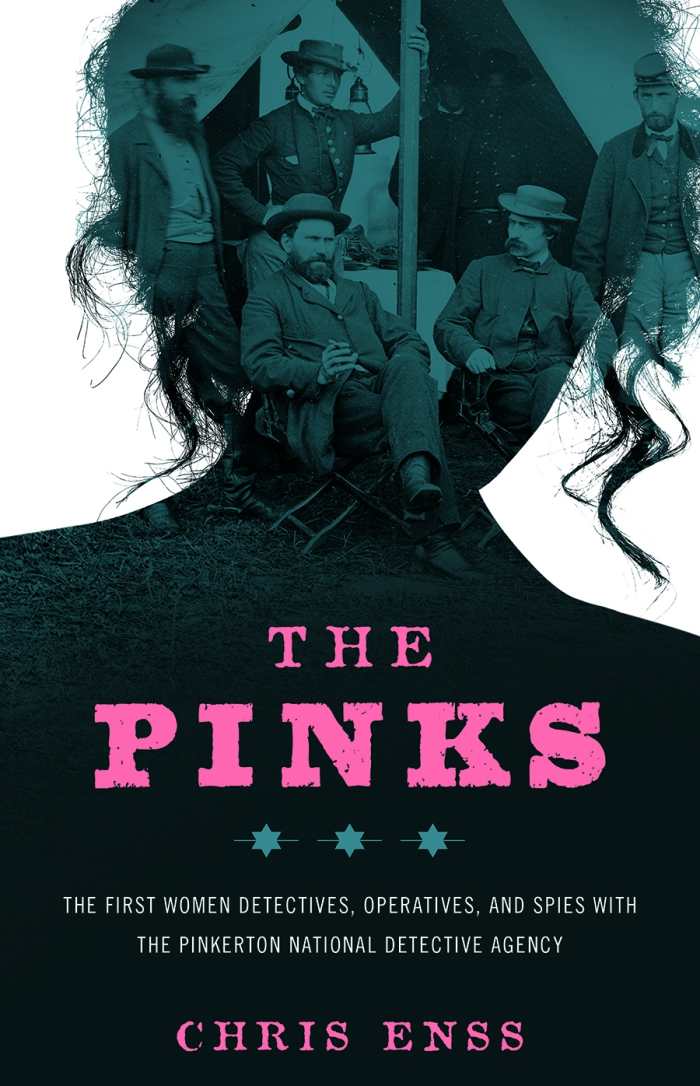

The Pinks

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

Chris Enss

TwoDot

Softcover $16.95 (192pp)

978-1-4930-0833-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

The Pinks reads like a historical thriller, with one fascinating plot twist: it is based wholly on truth.

Chris Enss’s The Pinks offers an engrossing look at the women’s flank of the famed Pinkerton group, which provided services of security, protection, investigation, and, in many cases, infiltration by its initially all-male staff of “private eyes.”

Allan Pinkerton had an innovative and invasive approach to dealing with crime and criminals. After immigrating to the United States from Scotland, he eventually established the Pinkerton offices in Chicago. Six years after the agency opened, Kate Warne had the audacious foresight to apply for a job as a Pinkerton detective, despite the fact that Pinkerton himself had never considered hiring women. Warne argued that women could assume undercover roles as ably as men, and that feminine intuition and charm could help them excel as undercover agents.

Though Pinkerton knew the work would be dangerous, he hired Warne and assigned her to numerous cases. Enss depicts Warne as an excellent actress, able to alter her appearance, accent, and mood quickly and convincingly. Pinkerton’s investigations were often complex and went on for extended periods of time as the agents gained the confidence of key individuals—or the guilty parties themselves. Warne rose to every challenge, including escorting a disguised Abraham Lincoln to Washington via train in 1861. The then president-elect was in danger of assassination by a Baltimore cadre of secessionists who wanted Lincoln dead before he even had a chance to take office.

The Pinks notes how Warne’s success encouraged Pinkerton to employ other women, placing them in roles of general investigation or even espionage during the Civil War. They pursued murderers, carried classified documents, decoded messages, and maintained their cover in highly charged situations. Ultimately, the Pinkerton logo became that of a watchful female eye, accompanied by the apt motto of “We Never Sleep.” However, despite Pinkerton’s equal-opportunity mind-set, official American police forces did not hire female detectives until the late nineteenth century.

The Pinks details Warne’s career as a Pinkerton detective, along with various other cases assigned to female agents like Hattie Lawton, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, and the artistically gifted Lavinia “Vinnie” Ream. Filled with intrigue, suspense, bravery, and women’s accomplishment,The Pinks reads like a historical thriller with one fascinating plot twist: it is based wholly on truth.

MEG NOLA (June 27, 2017)

The Only Woman in the Room

Episodes in My Life and Career as a Television Writer

Rita Lakin

Applause Theatre & Cinema Books

Hardcover $29.99 (296pp)

978-1-4950-1405-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

At turns hilarious, tender, and tough, this is the fabulous memoir of a woman who forged her own path to the writers’ room in an industry dominated by men.

If you like classic television, you’ve probably seen Rita Lakin’s work. Dr. Kildare, Peyton Place, Flamingo Road, Mod Squad. In an industry dominated by men, Lakin worked her way up in the writers’ room—and worked her way into a better life for her and her children as she made her mark on the small screen.

The Only Woman in the Room chronicles how Lakin crafted a new career out of necessity, and what a bonus that it was a fabulous, successful career. She had just lost her loving husband and had three children to raise. It was the early 1960s, an era not kind to a widowed young mom. She ventured out, talking her way into a secretarial job at Universal Studios when she couldn’t even type. She ventured even further out, trying some script writing through a kind boss willing to vouch for her with his colleagues. From there, piece by piece, gig by gig, TV series by TV series, she built a great reputation in the field and nabbed some plum jobs, plus the better house and life that went with it.

Lakin is at turns tender in remembering her late husband and tough and honest in relating the incidents where she got trashed. She’s wise to what was going on around her, yet unafraid to admit how insecure she was in her work. She writes, “I never chased after an assignment; each one I did came to me. And I took whatever was offered. I had no ego. … And here I was, a successful woman in spite of myself.”

Jobs weren’t the only things that flitted strangely into her life. Lakin’s tales of the mobster who wanted to “keep” her and the sheik in the elevator are hilarious, the sort of truths that are stranger than fiction. Her writing style is effortless, seamless. The pages zoom right along. Two veins of glossy color photos in the book nicely provide faces with names.

Lakin can only be admired—by both women and men—for forging a marvelous path through fears and heartbreak. Was it a charmed career? No. One clearly earned.

BILLIE RAE BATES (November 27, 2015)

Hannah Hohman