Destination Quế Sơn: Mix Romance, Mystery, and Intrigue, with a Touch of Combat; then Stir Carefully.

At best, historical fiction helps you experience a time and place with the seeming precision of memory or nostalgia. You may not have actually been there to see the events but the talented novelist offers a close second.

In Marines of Quế Sơn, Robert MacNichol executes this authorial feat with stunning results. In the interview below, Foreword‘s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland describes MacNichol’s background descriptions and wartime setting as akin to reading “a travel book to the Vietnam War,” and when the opportunity to connect with the author presented itself, he jumped at the chance.

Ryan, the discharged Marine back in wartime Vietnam working in the private sector who serves as your protagonist in Marines of Quế Sơn, falls in love with the daughter of a powerful South Vietnamese general. His unlikely presence and proximity to the upper tiers of Vietnamese society, offer a telling example of what an interesting place the war-torn region was during the 1960s. You are certainly well aware of the many, many thousands of other novels based on the Vietnam War—what made you feel like you could bring something new to the genre?

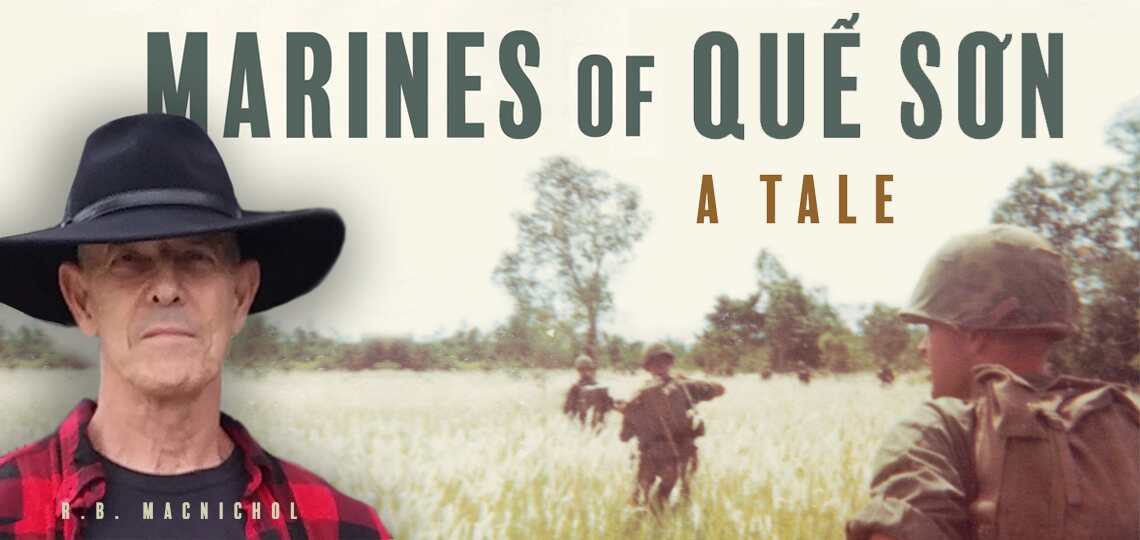

To be perfectly honest, I wrote this book for me. I really didn’t focus on the market. It was truly a labor of love. Of all the books out there, I confess to reading very few. There have been exceptions. While my fictional and biographical reading list is short, my history book list is quite long.

Marines of Quế Sơn combines some history and some perspective through the eyes of Marines and Vietnamese, with my personal experience and research. Vân is based on my wife. I met her at Camp Pendleton in 1975. She was born in Hanoi and grew up in Saigon, in a military family. Every time I read my story I fall in love with her all over again, and I enjoy my adventure in Quế Sơn once more.

Vietnamese are an integral part of Southern Californian society. Little Saigon is just up the road, to the north. Camp Pendleton is just to the south; I’ve known almost every inch of that base since 1966. There are a lot of memories there, including those of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees. I know many of these people and their stories. I base my book in part on those experiences and interactions with both Vietnamese and Marines.

The story itself is nearly a memoir. Its sources are derived from a wide range of my experiences; before, during, and after the war. I condense it down to a time and a place: Quế Sơn, in 1967. It offers the reader a glimpse into my experiences in Vietnam, and with the Vietnamese. It expresses the romance (not just between lovers but in the allure of Quế Sơn itself), the history, the rumors and the myths such as Heaven’s Uncle and the ma cà rồng (Vietnamese vampires). The average story I’ve come across simply does not offer all of that. My story is very likely to be much different than the thousands of books and stereotypical movies out there, but it was never my goal to compete in the market. If it does, great. Personally, I’ve read and reread this book many times; I’m rereading it now. I enjoy the travel back in time—it’s an escape mechanism for me, as more memories come back to me with each reading.

What is also different is that the story is a positive one—I’ve not come across many of those concerning Vietnam. The Marines of Quế Sơn, in my story, are a close knit, special group of guys who find themselves serving in a strange and far off land. A year earlier many were high school students, their officers were not much older. I also wrote my view of Marines, Vietnamese, and Vietnam with a larger audience in mind, not just veterans of the war.

The Fifth Marine Regiment plays a vital role in Marines of Quế Sơn. Can you talk about their storied history?

In WWI, Fifth and Sixth Marines fought in the battle of Belleau Wood (it’s in France). During the Great War the Marines fought back and forth with the Germans over that place. It took five assaults under deadly fire to hold on to that spot, which today is a shrine. In one battle the French advised Marines who had just arrived to retreat. Captain Lloyd W. Williams replied, “Retreat? Hell, we just got here!”

Later, during an assault under withering fire, Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly (winner of two Medals of Honor) yelled, “Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?” The Marines in that battle were given the name Devil Dogs by the Germans. They were awarded the Fourragère by the French. They wear both the nickname and the award to this day.

In 1967, over a seven month period, Fifth Marines in Quế Sơn lost 900 Marines (KIA). By one account more Marines died in Quế Sơn than at Khe Sanh, Huế, or Cồn Thien. The enemy lost over 6000 soldiers (KIA); losses were so high that the enemy was unable to take control of Da Nang as they had the imperial city of Hue during the 1968 Têt offensive.

A side note: Some of the enemy in Quế Sơn were veterans of Dien Bien Phu, and some Marines were veterans of WWII and Korea.

Five Marines and one navy chaplain were awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously, twenty-seven Marines and navy corpsmen received the Navy Cross, and eighty-four received Silver Stars.

The Fifth Marines make up part of the First Marine Division. This division is known as the Old Breed. They fought at Guadalcanal, Peleliu, and Okinawa; later they spearheaded MacArthur’s Korean invasion at Inchon, and fought their way through six Chinese divisions at the Chosen Reservoir. This information can be found in a foreword, by Al Gray the 29th Commandant of the Marines Corps, in the book The Road of 10,000 Pains, by Otto Lehrack.

You go into great detail about the differences between rookie Marines and old timers, as they navigate the perils and discomforts of wartime Vietnam, but you also explore another interesting aspect of America’s fighting force in Vietnam: its ethnic and regional and cultural diversity, including Germans with firsthand experience in WWII, undercover CIA operatives and others leading double lives, and those soldiers coming from privileged backgrounds. Did the diverse mix make this particular war unique among America’s long history of overseas conflicts?

Diversity runs all through the Marine Corps and the military in general in various wars, and in many countries. I believe the French Foreign Legion is very diverse, for example. I worked with the French Navy in Hawaii and some of their sailors were from Tahiti, and another from Australia. In WWII, pilots from other countries flew for the British in the air war with Germany. In fact, the Waffen SS in WWII was a very diverse group consisting of soldiers from many countries other than Germany.

My battalion was not unique in this aspect. In real life, we had a gunnery sergeant from the area of Czechoslovakia/Hungary. I met a German sergeant in the hospital where I was treated for my wounds. I came across another Marine who was British, his father was in the oil business. We had a Canadian unit with our company at Phu Loc, where I was wounded. Another fellow in my platoon was Swedish. We had Filipinos, a Frenchman (from France), Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Native Americans. One Marine, who had served as a soldier in a Central American country, was ethnically German, another Marine was from Colombia.

As for the spies or secret agents, I attended the Defense Language Institute at Monterey, CA., where I was informed that some of the students might not be the rank they held nor did the job they said they did (i.e. a sergeant in the Army may not be a sergeant or even be in the Army). In Vietnam, we had a sergeant who could seemingly come and go from our battalion area as he wished. Sergeants can’t do that. I asked him where he went and what he did. He would only say, “I go out.” He seemed to have had special privileges no one could account for. Another sergeant came to our company at Camp Pendleton. He transferred directly from the Army to the Marines, he had never been to boot camp. I asked the First Sergeant what he thought was going on. He believed the fellow was a plant, or a spy looking for some information within our unit. I used these experiences to create secret agents in my story.

Unbeknownst to his fellow Marines in the Fifth Marine Regiment, platoon Sergeant Bolton is one of a handful of agents entrusted by the Pentagon to investigate whether there is a connection between rumored defectors hiding in the jungles and the special operations men who were listed as missing. As it turns out, many of your characters are suspicious to the point of paranoia about the guys they serve with. Everyone seems to be on the make. Again, it’s an eye-opening aspect of a seemingly familiar war. How did you come to develop that wartime dynamic?

Concerning the suspicion and paranoia, the treasure changes everything for a handful of people, but not for others. The rest of Bravo is busy conducting Marine Corps business as usual. I wanted to make hidden treasure part of the story, because I buried some money and valuables myself on Hill 51 in 1967. I have no idea if it’s still there, but I’ve been curious about it for fifty-four years. The whole idea of hidden treasure intrigues me. I read up on the subject of buried treasure in Vietnam. It ranges from Captain Kid’s treasure buried on Phu Quoc Island to Emperor Tu Duc’s treasure buried secretly somewhere outside the Imperial City of Hue to 4000 tons of gold buried by the Japanese in WWII, just for starters. I also experienced tunnels. Once I explored a tunnel by myself—that was really stupid—I couldn’t stop advancing even so. Finally, it ended and I turned around and left. While developing the story I wondered what if some Marines came across hidden treasure in some tunnel or cave? How would they deal with it? How might they come across it in the first place? And how could they get it out of Vietnam? I wove a scenario into the story about treasure, inside real tunnels and caves that we really did blow up. It took a while and was rather complex but I used my experiences to write a plausible tale around such a situation.

And, the rumor and paranoia is further heightened by tales of atrocious chemical weapons, 150 year old monks, Russians kidnapping US forces in Vietnam only to send them to gulags in Siberia, Quế Sơn’s “Devil’s Triangle” reputation for supernatural phenomenon, the mother lode of hidden treasure, and other spectacular notions. Is Quế Sơn a real place? What explains its mystique?

Quế Sơn is a real place. Once on patrol I checked the ID of a monk and the guy was 150 years old according to his ID. I use this experience in my story.

It was none other than Boris Yeltsin himself who alerted the US that Vietnam prisoners were in Soviet gulags. Reported in the LA Times: “Russian President Boris N. Yeltsin said Monday (June 16, 1992) that some US prisoners captured during the Vietnam War were moved to labor camps in the Soviet Union, and he speculated that some may still be alive.” I use this source for my story.

Sgt. Bolton refers to a MACV agent’s description of Quế Sơn as the Devil’s Triangle of Vietnam in a flat voice because he doesn’t really believe it. He then speculates that if only it was true, it might explain how the Phantom Blooper, Salt and Pepper, and the missing Special Ops Team seemingly popped up then disappeared without a trace.

Additionally, there are superstitions about vampires and other mythical beliefs. Quế Sơn’s countryside could seem very strange to eighteen and nineteen year olds in the dark of the night with booby traps, ambushes, firefights, and dead enemy or Marines at your feet. Such conditions can exaggerate rumors and superstition. A snake wraps itself around a sleeping Marine in my story—this really happened—how would one feel in this environment? Remember, tomorrow could be the day you die.

On a different note, Quế Sơn is near the once very wealthy, and ancient, port city of Hội An. Ships from around the world sailed there over the centuries. It was controlled by the Champa Empire, the Vietnamese, the Chinese, and influenced by India, Portugal, France, and the Japanese. Hội An was part of the Maritime Silk Road, that trade route stretched from the Mideast to both Europe and China. Trade from all over the world passed through this area.

It’s worth noting that Quế Sơn means Cinnamon Mountain—a reference to its rich past. It was part of the region where world famous Saigon Cinnamon was harvested and produced. All the above lends to the idea that Quế Sơn was a remarkable place because of its special location. All this history gives it a unique aspect and a certain mystique.

With the extraordinary detail you offer about the day-to-day in ’Nam, I often had the feeling I was reading a travel book to the Vietnam War. That sort of knowledge is only obtained the old-fashioned way. Please talk about your Vietnam experience and your personal connection to Marines of Quế Sơn.

What I’m about to tell could be told by any of the hundreds of Marines that served in Quế Sơn. Mine is only one story, and not as traumatic as some other accounts. But this a short list of my experience.

Two days, after being assigned to Bravo Company, I found myself carrying my dead team leader, until I collapsed and someone else carried him. He was finally put on a helicopter and taken away. I had been a few feet back when he stepped on a booby trap. I was originally in his place in the column. By chance, he told me to get behind him as we moved out—he was killed, I survived. After carrying him, I was covered in his blood and wore that shirt for most of the day before I could get a clean one. It was on that day that my remaining twelve month tour in Vietnam took on a whole different aspect. I write this into my story—everything in my book is based on actual experience.

I sometimes lecture college students and tell them that my unit basically camped out for a year. Occasionally, we slept in a tent on base (our tents only had dirt and weeds for a floor) but often we were just out in the open air.

In the story my description of a nighttime operation and waiting to move off the base is very accurate, down to the satellite that we would watch pass by overhead reminding us of home. We called America the “World” because it was the world of everything we knew, loved, and possessed, and surviving to return was not at all guaranteed.

Our camp-outs were interspersed with firefights where Marines were sometimes wounded or killed. Often we would watch our wounded or dead being carried off in a helicopter. I recall showing one college class some pictures of Marines in my unit, and adding that these guys aren’t wearing any underwear. The weather was hot and wet or hot and dry. We, more often than not, took a bath when we waded across a river. Underwear added too much clothing that irritated our skin, as we literally lived, fought, and worked in sweaty tropical conditions for months.

Every day was the same. When a navy chaplain gave a sermon we knew it was Sunday. When we were not on patrols, we were on bunker watch, or laying barbed wire, or reinforcing sandbag fortifications. Any news we received came to us in the form of a discarded Stars and Stripes newspaper usually days or weeks old. Our mail took weeks to arrive from home. Often folks back home knew more than we did about the news concerning Vietnam.

With all the guns and ammo floating around, of course there were accidental discharges and occasional friendly fire casualties. I witnessed two accidental discharges that wounded unlucky bystanders. There was one other but I only saw a Marine being carried off on a stretcher.

Once a mortar was firing from our base camp at night. As I was about to fall asleep, I heard someone yell, “Short round.” I lie there waiting for it to come down—somewhere. It landed two tents down and killed or wounded everyone inside.

On operation Swift, six Marines in Bravo Company were killed by rockets from a jet as Second Platoon rushed forward to help a downed helicopter. The rest of Bravo was in two columns that followed close behind. We were machine gunned twice by a Huey circling over head. Incredibly, no one was hit. From the air we looked like the enemy—the pilots were trying to protect the crew of the downed craft.

Another buddy of mine, and a gunny he was with, were hit by our own artillery—the gunny died. My buddy, who survived the errant round, told me that he lay there all night praying that God would let him die in a bed with clean sheets, not in a rice paddy, in the dirt. That’s all he wanted as he waited to be medevaced—helicopters were slow to arrive in the heat of a nighttime battle.

Some Marines were caught behind enemy lines on Operation Swift and died horribly. One fellow I knew was found with bullet holes in both wrists and his forehead; seeing his body was very disturbing.

I had what I call a Zen-like experience on Swift. We were in a foxhole when my Company Commander said, “We’ll be overrun at any moment.” Strangely, I wasn’t afraid. In fact, I felt totally at peace. I completely believed we were about to die by waves of communist soldiers. We were not overrun, thank God, but after that episode I felt as though I knew what the men at the Alamo might have felt facing overwhelming odds and certain death.

Years later I read about a Japanese officer on Iwo Jima. He was facing an overwhelming attack, he knew he wouldn’t survive. He wrote that he had a feeling he described as “A beautiful emptiness.”

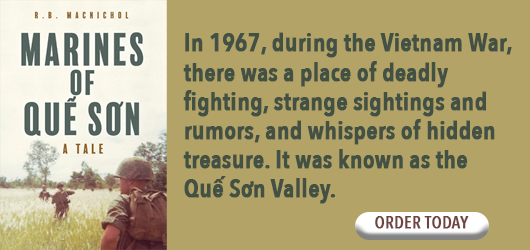

Marines of Quế Sơn

R.B. MacNichol

FriesenPress

Unknown (374pp)

978-1-5255-6142-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In the humane historical novel Marines of Quế Sơn, men in a war-torn area face internal battles, too.

In R. B. MacNichol’s historical novel Marines of Quế Sơn, soldiers and civilians are brought together in the middle of the Vietnam War.

Ryan, a private security officer, like Corporal R. D. Sanders and Sergeant Bolton, is on an important personal mission in Quế Sơn, a war-torn district. Ryan is there to meet his fiancée, Vân, at a compound deep in the bush; Bolton is searching for MIA marines and potential defectors; and Sanders wants to destroy any and all enemies in the valley, all while keeping those in his squad alive. But the men have to balance their agendas with their reliance on others around them if they are going to survive.

Though it is set up as a familiar war story focused on the bonds of a single squad of soldiers, the book’s story line is in fact multifaceted and complex. In the place of action scenes, there’s a lot of waiting, watching, and planning involved, but rather than dragging on, such sections are involving. They make ample room for characterization via shared back stories. The book’s many developments are both unexpected and earned, and its unhurried, gradual build and sustained tension make it engrossing. The setting—wartime Vietnam—is addressed in suitable measures, too, with descriptions of combat that are vibrant and satisfying.

The lives of soldiers in Vietnam are portrayed in an accurate, immersive manner. Their daily challenges feature military operations, but also make room for forays into Vietnamese culture. The result is a robust atmosphere that’s deepened by dialogue, wherein gallows humor and dark musings share space with tender sentiments between lovers.

The book’s thoughtful diction makes use of era-appropriate terms and phrases, as well as relevant military jargon. Its descriptions are clear, and its mentions of famous war rumors, as of rock apes and the notorious defectors Salt and Pepper, inspire interest in aspects of the war that exceed common knowledge. Audiences will leave the book with a stronger knowledge base of the war, but also having spent time with dynamic characters who are prone to both selfless acts and selfish actions, and introspection and spontaneity in turn. Their plausible behavior results in uncommon narrative depth.

The dramatic historical novel Marines of Quế Sơn is set during the Vietnam War, whose dangers and ugliness are acknowledged, and whose players are humanized as they battle internally, too.

IAN DAILEY (April 10, 2021)

Matt Sutherland