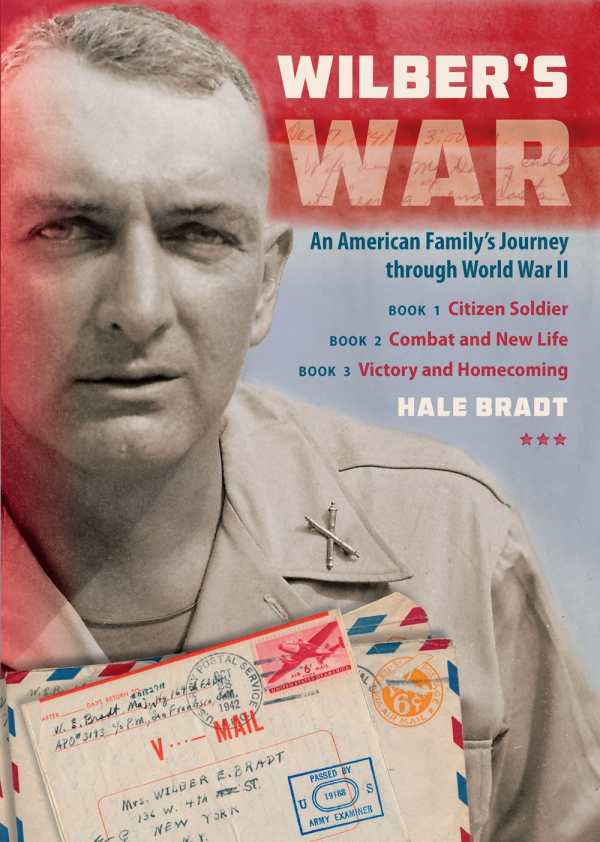

Wilber's War (a trilogy)

An American Family's Journey through World War II

- 2015 INDIES Winner

- Silver, War & Military (Adult Nonfiction)

Three years in the Pacific Theater during WWIl leads to 700 intimate letters, but this story is less about a war hero than it is about a loving family man.

In his weighty trilogy (nine pounds on the bathroom scale) in honor of the father World War II deprived him of ever fully knowing, Hale Bradt relates a story that could resonate with the multitude of families who also sacrificed a father, a husband, or a son. It might also serve as a reminder to those who celebrate war, and to those who would wage it, of the often joyless consequences.

Bradt, a retired MIT physics professor who is now in his eighties, began this project in 1980 as he perused the 700 or so letters his father, Wilber Bradt, wrote to his family and others while serving as a US Army officer in the Pacific Theater from 1942 to 1945. The result is a story less about a war hero—although Wilber, whose awards included three Silver Star medals and a Purple Heart, surely was one—than it is about a man bereft of family and maybe a little bit afraid.

Shortly before the invasion of Luzon in the Philippines in January 1945, he wrote his wife, Norma, “Don’t forget that if I don’t come thru, some minutes are worth more than years of living and such minutes are coming to us. … I love you and nothing can take me away from you.”

Wilber also wrote very personal letters to his son and daughter. Hale Bradt admits to resisting tears as he reads a letter telling him not to be afraid and to wait for “the good days we will have together some day.” It was not to be. Hale was 14 the last time he saw his father, who was home after a three-year absence but hospitalized periodically for treatment of malaria and the aftereffects of wounds. Poignantly, their second-to-last father-son outing was to a Fritz Kreisler violin recital. Both loved classical music.

On December 1, 1945, Lt. Col. Wilber E. Bradt, 45, committed suicide by shooting himself in the chest with a .45-caliber pistol. In the parlance of those times, he was probably a victim of “shell-shock,” a term largely replaced in this more euphemistic era with “post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Reviewed by

Tom Bevier

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.