It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

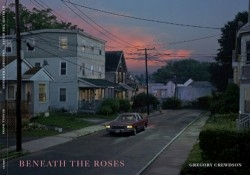

Beneath the Roses

There is a woman dressed like a librarian cliché seated on a small bed. Her expression is crushed. Look at her left hand, palm up—it appears almost paralyzed, like it’s lost its grip. A laundry basket of meticulously folded pale pink sheets sets in front of her. What’s that on the bedsheet? Blood? Whose room is this? Garish satiny underwear scattered on the floor, pots of pink nail polish bunched on the nightstand, framed prints of ballet dancers above the bed—this is a daughter’s room, of course. An altar of blue light frames the window and a pile of cartoonish children’s books. The door is open. The blue light escapes to the hall and beyond.

The next picture shows a man sitting his socks in a wingback chair in his living room. He looks stunned. Something immense and heavy—or perhaps just something traveling at an enormous speed—has crashed through the roof and ceiling and is now glowing in the basement. It’s the same blue glow as that of the TV. On second thought, no, nothing has crashed. The house is a ruin. Plaster has fallen from the walls revealing the lathe like bones. There’s dirt and newspapers and cement blocks in heaps. Tile is piled by the closed entrance door. The man in his socks isn’t so much shattered by the ruin as flattened by it. There will be no reconstruction. There is no more going forward.

Born in Brooklyn in 1962, Crewdson has been taking still pictures that use complex cinematic techniques for twenty years. Working with set designers and lighting artists on sound stages and on the streets of rural towns in Vermont and Massachusetts, the prints are large (64 x 94), the colors glossy, the themes operatic.

There is dread, but there’s yearning too. A certain adolescent miraculousness. And a kind of obsessive feral nostalgia. It’s gleaming twilight in the rundown mom and pop neighborhoods, land of uneven lawns and sunken concrete sidewalks, refuse pressed down beneath a season of snow. Trailers are dwarfed by enormous deciduous trees, the rooms are spacious and the surfaces cluttered, the people wear the posture of defeat and estrangement. In an NPR interview, Crewdson said that his pictures must first be beautiful, but that beauty is not enough. He strives to convey an underlying edge of anxiety, isolation, and fear. Yes, the house is on fire, the children not at home—no, they’re walking singly and in pairs along the railroad bed, overgrown with goldenrod. Here there are terrible choices, or the tragedy of the lack of effort to make any choice at all.

There is also the quiet sadness of beginnings and ends. In a Guardian interview, Crewdson said, “My photographs are about the moment of transition between before and after. Twilight is evocative of that. There’s something magical about the condition.” All of the photos are indeed mysterious: What are the teenagers doing in the forest with their flashlights? Why have they dug the hole? Did they dig it with their bare hands? In so many of the pictures bathroom doors are open—the toilet, wastebasket, the aqua tiles, the bath rug, soap, the pharmacy bottles want to tell their story—is something about to happen or has it already taken place?

The last section of the book is made up of production stills, lighting plots, and Polaroid snaps documenting the location shoots. Smoke and fog and snow machines fill up the atmosphere and lighting reaches four stories into the air. Architectural plans and set drawings are included for the soundstage shots. Interestingly, the incidental actor on scene looks as heartbroken candid as posed.

Twilight is a place to play with what you can see, what you can almost see, and what you can’t see at all. Although movie-like in their composition and the almost liquid intensity of depth, they’re non-manipulative. Unlike a movie’s deliberate gaze upon an object that’s sure to become important later on, these pictures are open-ended and viewers are invited to bring their baggage. As poet and novelist Russell Banks says in his introduction, “Crewdson’s photographs engage the mind more like good fiction than movies.” We might make the wish, like Timothy Hutton’s character did to Natalie Portman’s character in Beautiful Girls, “When you leave here, take me with you.”

Reviewed by

Heather Shaw

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.