Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Anneliese Abbott, Author of Malabar Farm

Alongside all the other reasons to be discouraged by the state of our union is the bitter divide in farm country between conventional farmers who rely on fertilizers and herbicides and the organic types who work to replenish the soil using sustainable practices. This disagreement is especially sad because both sides see the merit in adapting some of their counterparts methods; they just can’t find the perfect meeting place to sit down and learn from each other.

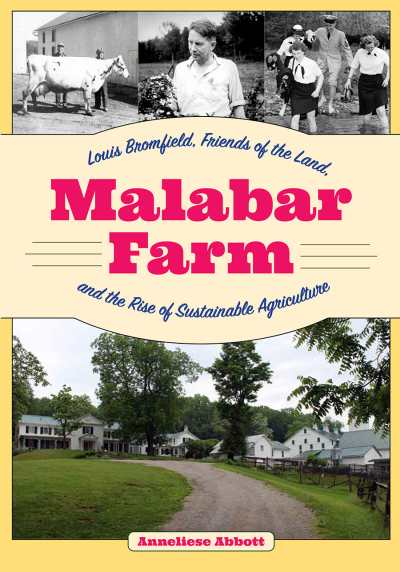

This week’s history lesson takes us to Ohio in the more cordial 1930s and 40s where we meet the extraordinary character of Louis Bromfield—farmer, novelist, public speaker, conservationist, agricultural futurist—an overlooked but hugely influential force in our nation’s farming history. In Malabar Farm, biographer Anneliese Abbott “chronicles the significant history of what was once a small private farm, and is now a state park, recreation area, working farm, and living history site,” in the words of Rachel Jagareski in her review for Foreword’s January/February issue.

We’re suckers for encouraging stories from the farm front, so with the help of Kent State we put reviewer and author together for the following chat.

Your book richly uncovers the important role that Louis Bromfield and his Malabar Farm played in American agricultural history. I was only aware of Bromfield as a popular novelist, and it was enlightening to read of all of his accomplishments in soil conservation and innovative agriculture. Bromfield certainly comes off as a dynamo, leading scores of visitors on farm tours, preaching the gospel of soil science across the country during the 1930s and 40s, and trying out numerous farming techniques over decades. What personal characteristics do you think molded him into such a unique and visionary agricultural innovator?

Yeah, Bromfield was quite a unique person! He had a lot of passion, and when he turned that passion toward agriculture, that really helped him persuade people. He had a great flair for storytelling and was a wonderful public speaker as well as an author. He also had an interesting combination of being nostalgic for the past of American agriculture while wholeheartedly embracing new technologies for the future, which appealed to a wide range of people in the 1940s. And he doesn’t seem to have really cared what people thought of him; he came across as a genuine farmer who got his hands in the dirt and wasn’t worried about accidentally offending someone. He had a great gift for taking ideas from lots of different people, putting them together into a coherent system, and popularizing them.

As your preface indicates, this volume stemmed from your 2016 undergraduate honors thesis. (That is quite an achievement, congratulations!) What particular sections were most revised to flesh out the finished book?

The biggest revision to my thesis was the addition of all the historical context material. My thesis was mostly based on archival documents and the Friends of the Land magazines; all of the background about soil conservation, conservation education, grass farming, dairy farming, ecology, organics, feeding the world, the environmental movement, and more came from those four years of background research between the thesis and the book. Ninety percent of the sources listed in the bibliography were not in my thesis.

My thesis stopped in 1976, so another important addition for the book was coverage of Malabar Farm under state ownership. I drew heavily for that on interviews with former park managers, especially Jim Berry and Louis Andres, who really helped bring that period alive for me.

And then I went back through the whole thing and revised it many, many times to work all of that information into the narrative. The basic story of Malabar from 1939 to 1976 is the same in the thesis and the book, but only the book puts Malabar in its historical context and brings the narrative up to the present.

You note that the achievements of the American soil conservation movement and Friends of the Land have been largely subsumed in postwar agricultural history texts and the focus directed instead on advances with chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and modern farming methods. What do you see as the future of American farming: a blend of this kind of conventional farming and organic agriculture? Or some other direction?

I always avoid making predictions about the future because I would likely look back at them in thirty years and say, “Boy, I was sure wrong about that!” But I can say what I would like to see happen, and that would be for conventional and organic farmers to start talking to each other and work together to make a more sustainable agricultural system.

What I see as the biggest barrier to sustainable agriculture right now is the increasingly polarized divide between conventional farmers and environmentalists, along with fracture and polarization in the sustainable agriculture community. Much of the current infighting is eerily reminiscent of the fragmentation of the conservation movement in the 1950s, which led to a reversal of so many of the conservation gains made in the 1940s. My hope is that by raising awareness of this history, sustainable agriculture advocates can heed the warning of what happened to their predecessors and focus on common goals instead of differences.

I think Louis Bromfield summarized the overarching theme of sustainable agriculture very well—working with nature instead of against it. In the long term, that’s the only kind of system that will succeed, regardless of what word is used to describe it. But will that happen soon, or will things get worse again like they did in the 1950s? Only time will tell.

Bromfield may have had boundless energy and intellectual curiosity, but your book also points out the substantial government and corporate contacts that he tapped for his farm, including Civilian Conservation Corps labor and free Ferguson tractors. How might other less well-connected farmers develop these kinds of programs?

Yeah, Bromfield’s conservation and corporate connections certainly helped him out a lot in his soil conservation work. What he and his contemporaries always said was that the average farmer could do the same things; it just might take a little longer.

In the 1930s and early 1940s, many “average” farmers did get free CCC labor on their farms, especially if they lived in one of the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) demonstration areas. And anyone could get the SCS to draw up a land-use plan for their farm. So I would say that the savvy farmer of the time could get almost as much government support as Bromfield did if they were in the right place and knew the right people to talk to.

As far as the corporate sponsorship goes, Bromfield definitely had an advantage there. Of course, the average farmer wouldn’t have purchased nearly as much equipment as Bromfield had, but yes, paying market prices for it would have set them back a lot more than it did Bromfield.

The bottom line is that other farmers could do at least part of what Bromfield did, but it would probably take longer and cost more.

Malabar Farm’s midcentury sidelines selling pesticide-free vegetables at roadside markets and offering farm grown foods at its restaurant were certainly years ahead of their time. What do you think Bromfield would make of the growing popularity of farmer’s markets, organic foods, and farm-to-table dining?

I am often asked what Bromfield would think if he was alive today, and it’s really hard to know because he was very much a man of his time. It would make a huge difference whether he had lived through the intervening years or was suddenly transported to 2021 from the 1940s or 1950s. I’d say that if you could show Bromfield today’s world in 1954, when he started his vegetable stand, he would love the farmer’s markets, farm-to-table dining, and other aspects of the local food movement. He might have even done a CSA if such things had been popular during his time. I think he would like the Slow Food movement with its emphasis on flavorful heirloom varieties and carefully prepared cuisine.

It’s harder to say what he would think about the USDA organic certification program. Bromfield liked the idea of some kind of label certifying that foods were grown without pesticides; what I’m not sure about is how he would have felt about the organic ban on chemical fertilizers like superphosphate. I think he would have really liked the idea of low-input sustainable agriculture that was advanced in the late 1980s and early 1990s; that was very similar to his philosophies.

I think Bromfield would be shocked to see how his New Agriculture turned into agribusiness and led to less than one percent of the US population currently being involved in farming. I don’t think he or any of his contemporaries could have imagined just how big and impersonal industrialized agriculture would grow.

After Malabar Farm became an Ohio state park in the seventies, another energetic innovator, Jim Berry, became park manager and greatly expanded the site’s programming and attendance as a demonstration farm and heritage/historic site. Do you see parallels between Bromfield and Berry as motivators and leaders?

Well, I’ve actually talked to Jim Berry and I never met Louis Bromfield, but I would say that they were both very passionate about Malabar Farm. They were also both very up on the trends of their time periods and tried to make Malabar culturally relevant. So I would say that they had similarities in their passion for the farm, the environment, and sustainable agriculture.

But they also had very different personalities. Bromfield was notoriously poor at managing money; Berry turned Malabar into an income-generating park. For Bromfield, the tourists were mostly incidental to his work; Berry’s whole job was to get more tourists to visit Malabar. They were both strong leaders, but in different ways. Bromfield was a charismatic leader who followed his passions wherever they led; Berry was a good manager who started with a specific goal and had amazing success attaining it.

What I love about the history of Malabar Farm is that so many different people have left their unique marks on it. Both Bromfield and Berry played an important role in making the farm what it is today.

What would Bromfield make of Malabar Farm today? Would he view the changes in the land, buildings, and management as successful adaptations? Or would he be unsettled by the Farm as a park with its conflicting missions and management by various state agencies? What would he be most proud of?

Again, this is one of those things that we can’t know for sure. I think that if you could transport Bromfield from 1954 to 2021 and show him Malabar Farm, he would be happy to see his Big House preserved. He would probably like the Maple Syrup Festival and Ohio Heritage Days because he was always nostalgic about pioneer history. He would really like the French cuisine at the Malabar Restaurant. He probably wouldn’t mind that the dairy is gone since it was already unprofitable before he died.

He’d be sad that the health department turned off the water in his vegetable stand. He’d be sad to see no-till soybeans planted into soybeans going up and down a hill, which is what I saw when I visited in 2018. I think he’d also be sad to see that the main focus of the house and farm tours is on his literary career and celebrity friends instead of soil conservation and his farming methods. He would probably like to see more agricultural demonstrations and education, maybe some pastured hogs and a vegetable garden again. I don’t think he would mind having the farm in state ownership, but he would be sad to see how it has been used as a political football. Overall, though, I think he would be proud to see that his legacy has been preserved and has had an impact on the sustainable agriculture movement.

Rachel Jagareski