Reviewer Laura Leavitt Interviews Hafsa Lodi, Author of Modesty: A Fashion Paradox

Stereotypes are sticky, they’re tough to shake loose. What comes to mind, for example, when you think about women’s clothing in Middle Eastern countries with strict dress codes? Black, tent-shaped garments, seemingly designed to cover as much skin as possible? That’s the image of Muslim women we see so often in the mainstream media. And many of us can’t help feeling these women are repressed by their religion, and dress that way reluctantly.

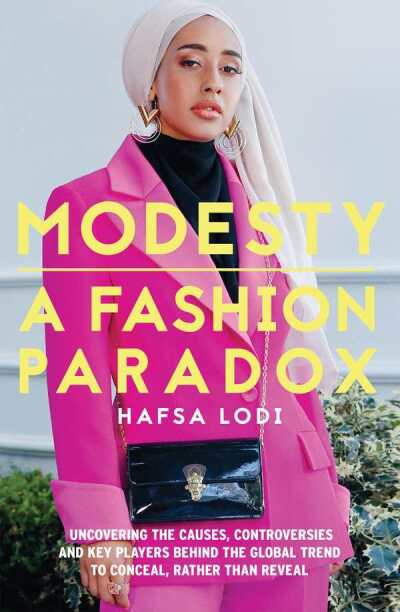

But that caricature is misleading, and far from the whole story. Furthermore, what we might call Islamic fashion has “led to the emergence of a global modest fashion movement—one that has inspired even non-religious women of all types of backgrounds to use clothing to conceal, rather than reveal,” writes Hafsa Lodi in her newly released Modesty: A Fashion Paradox. In fact, Lodi says, covering up is viewed by many women around the world as empowering.

An American fashion journalist based in Dubai, Lodi is perfectly positioned to help us understand what’s taking place in the clothing world. After Laura Leavitt wrote a glowing review of Modesty in Foreword’s May/June issue, we worked with Neem Tree Press to get reviewer and author together for this conversation.

Laura, take it from here.

In the book, you talk about the many influences that have made this an important time for modest fashion. What are the main forces or cultural moments do you think have brought about this particular explosion of interest?

It may not seem like such an obvious connection, but I think the explosion of the streetwear trend, which champions loose and comfortable “tomboy” cuts and favors clunky, athletic trainers, over impractical heels, has really attributed to the mass acceptance and popularity of modest fashion. Streetwear and sneaker culture celebrate comfort over sexiness, and so does modest fashion.

Speaking from a non-fashion perspective, we cannot discount the #MeToo movement’s influence on the integration of modest fashion in Hollywood—specifically on red carpets. An Elle article by Kenya Hunt aptly stated, “The #MeToo movement against sexual harassment and assault heightens the collective ‘need’ to shield one’s body.” Brands like Jimmy Choo were forced to pull ads that glamourized sexist, sex appeal, and the industry overall has been pushed to rethink how it portrays women’s bodies. Fashion-conscious women often look to red carpet style for inspiration, and after the Harvey Weinstein scandal, many Hollywood celebrities took to wearing more demure, elegant dresses for red carpet premieres, as opposed to the sultry looks that were previously in vogue.

The rise of modest fashion has also occurred hand-in-hand with the rising popularity of Muslim women in the limelight—like congresswoman Ilham Omar, and hijab-wearing model Halima Aden. Seeing them thrive, other Muslim women in the West are being inspired to use their platforms to portray positive, and “fashionable” images of Muslim women, countering the images of the all-black, oppressed, foreign and intimidating images often circulated by the mainstream Western media to illustrate Muslim women.

Do you sense a trend that a larger percentage of girls and young women are embracing different, more natural, more individualistic, attitudes toward beauty than previous generations? Is female beauty itself changing, and does the modesty trend reflect that?

While fashion and beauty bloggers have become almost notorious for posting over-the-top photos with caked-up makeup and piles of designer fashions, there is definitely a movement brewing that celebrates more natural, individualistic attitudes towards fashion and beauty. Open pores, blemishes, grey hair, and bags under the eyes are not necessarily seen as “ugly” anymore, and many women have started posting makeup-less selfies on platforms like social media. The modesty movement, which celebrates demureness and comfort over ostentatiousness and sexuality, shares similar values with this overall movement away objectifying and sexualizing women’s bodies. Grown-out eyebrows are in vogue, as is curly, natural, non-chemically-treated hair, and women are being called to embrace their natural beauty in the name of “self-love.”

That being said, women’s bodies are still being glamourized and sexualized in mainstream film and fashion. Occurrences like the cancellation of last year’s Victoria’s Secret fashion show are small steps towards rectifying this, and to helping women feel comfortable in their own skin—along with giving them the freedom of choice to cover or show however much skin they are comfortable concealing or revealing, without fear of ostracization.

You include some of yourself and your experiences of fashion in the book, despite it being a deeply journalistic text. Did you find your own fashion sense or preferences evolve while you wrote the book, and if so, how?

While Modesty: A Fashion Paradox is a journalistic text, it was important for me to include some of my own experiences since I view myself to be part of the “modest fashion” target market. As a Muslim woman, the topic of modest dress is an ever-evolving journey for me. Over the years, my own interpretations of modesty have gone through many changes, and they continue to do so now, even after the book has been published. My views on burkinis, for instance, keep becoming more positive the more I’m exposed to fashion-forward, stylish designs. I think I even explicitly wrote that I would never wear a burkini, in the book, but I may have to retract that statement—I’ve seen such cool, surf-inspired designs with beautiful floral patterns that are sure to protect wearers from sunburn.

I’ve also become more open-minded about niqabs, or face veils, which are worn by only a minority of Muslim women, and are often seen as “extreme” forms of modest dress—but speaking to women who cover their faces, coupled with the widespread adoption of face masks due to COVID-19 has really changed my personal views and perceptions about women who cover their faces. Perhaps it’s not as “extreme” as we often think it to be—perhaps, motivated by ideals like modesty, privacy, and segregation, they are simply exercising the right to choose how to dress. For so long we as society have deemed it to be “extreme,” “hostile,” and “intimidating,” but at a time when most of the world is covering their faces with medical masks, perhaps we will rethink our views.

What prompted you to take what was clearly already an interest in fashion and a background in journalism and delve into the book project?

To be honest, if it weren’t for Archna from Neem Tree Press, I would probably have never embarked on this journey to write a book about modest fashion. I never even thought of writing a book, be it fiction or non-fiction, before she approached me with the proposition of a lifetime: to fully immerse myself into a topic I had been exploring through journalism for years, without the tight word limit that always seemed to hold me back while writing for newspapers.

There seems to be a tension between the core concept of modesty and some of the goals of fashion influencing, which often include to be seen and admired. Can you tell me a bit about how the influencers you spoke with discuss that tension, where they are both modest and influential in fashion? How are those two elements resolved in their work?

Most of the modest fashion influencers I spoke to understood that traditional, ultra-conservative schools of thought may not be open-minded enough to accept fashion blogging, even in fully skin-covering outfits, as a “modest” practice. Their general views were that social media is a huge part of the reality we currently live in, and it provides a platform where you can inspire and touch followers from across the globe. They felt that the ideals and styles they were promoting were modest, positive, and championed diversity and inclusivity, and could help influence other women who followed modest lifestyles but perhaps lacked the confidence or support system to fully embrace the fun and creative relationship that can exist between faith and fashion.

Some of the women I spoke to try to promote different charitable initiatives, mosque, or community events, or other motivational stories of women, in addition to posting about fashion. Many of them try to strike a balance between fashion and other, less-frivolous features of daily life, and while many of them do post selfies of themselves, they acknowledge that there’s a fine line between posting occasional portraits and becoming narcissistic.

In the book you mention the phrase “modest is hottest,” which resonated when you were younger but your interpretation and opinion has changed. What are your hopes for the future of how women and girls aiming for modesty will see themselves and see modesty?

I think that I came across the phrase “modest is hottest” at an important time in my life, as a young teen living in Canada, without many positive role models or influences that celebrated modesty. It validated my dress code and made modesty sound “cool.” At 14, I wasn’t intellectual enough to linguistically analyze the meanings of the phrase, and how it could have potential negative impacts on young women. Some argue that it deceivingly teaches girls that they should aspire to look “hot” for the pleasure of men, but I don’t wholly agree with this argument. As a phrase on a T-shirt, I see no harm in it. In a very simplistic, catchy, and cutesy way, the slogan promotes modest fashion—a topic that is already very highly debated.

I’m happy that young women growing up in the West now, who follow modest lifestyles, have positive role models to look up to, outside of their families and religious communities. They can simply open their Instagram apps to see countless images of women in the same boat as them, and others who fall on different points of the “modesty” spectrum. Because modest fashion is not a black-and-white movement, I hope that young women will accept the many different interpretations of modesty that exist, and I hope that they’ll learn to suppress their judgements and “policing” of women who don’t conform to the same modesty codes that they do.

I also hope that their lifestyle choices will be validated and catered to in mainstream retail, and that shopping for modest fashion will never again be the challenge it once was—and with modest fashion being deemed a booming, multi-billion-dollar industry, I’m confident it won’t be dropping from the radar of mainstream retailers anytime soon.

What do you think is next for modest fashion? Are there nascent trends that you expect to become widespread in the coming year or two?

I believe that modest fashion has established itself as a retail category that demands covered-up cuts: high necklines, long hemlines, long sleeves, and loose fits. But there is more to just the aesthetic and design of the clothing—now, modest fashion needs to further develop the ideals influencing the wider fashion industry—like diversity, inclusion, different body sizes, and sustainability, for example. I believe that, like mainstream designers, modest fashion brands will start using more ethnic models and more plus-size models in their campaigns, and will devote more time and resources to creating clothing that’s eco-friendly or vegan.

I also think we will start seeing more focused modest fashion brands, specializing in key categories like athletic wear, swim wear, wedding attire, and loungewear—with so much competition emerging in an increasingly saturated market, branding and marketing will play critical roles.

Laura Leavitt