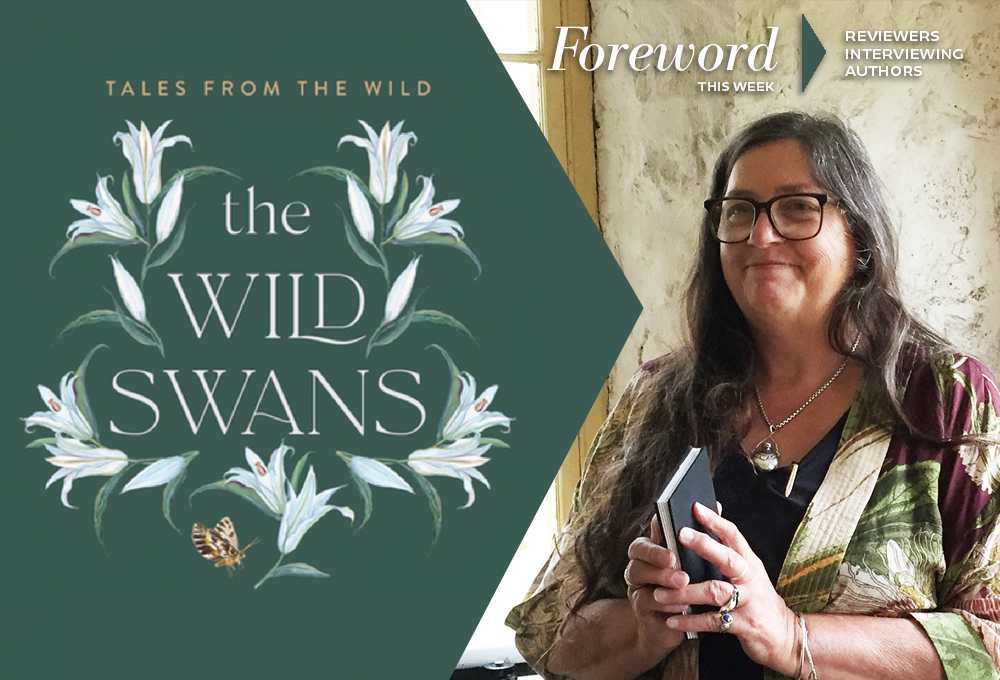

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Jackie Morris, Author of The Wild Swans

You need some serious nerve to take on a classic—especially one from a legend like Hans Christian Andersen, author of such hits as The Ugly Duckling, The Snow Queen, The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Clothes, and The Red Shoes.

So that’s why we were intrigued to come across a new version of Andersen’s The Wild Swans by Jackie Morris, who has written and illustrated more than forty children’s books including The Lost Words and The Lost Spells, two splendid collaborations with Robert MacFarlane.

No surprise, then, that Jackie’s retelling of The Wild Swans earned a glowing review from folklore scholar Jeana Jorgensen in Foreword’s September/October issue. The thought of connecting Jackie and Jeana together for a conversation was too compelling for us to pass up.

Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans is just one of many versions of the story of the girl whose brothers are turned into birds; other notable versions include The Six Swans, The Seven Ravens, and The Twelve Brothers by the Grimms, as well as numerous versions from oral tradition all over Europe. What drew you to the Andersen version and made you want to do your own retelling of it specifically?

To be honest, I wasn’t aware of the ownership of most of the stories. In my head there was also the Irish tales of swan folk, and Nordic. And for a while I toyed with turning the brothers into ravens, as I live in a place blessed with the song of ravens, their flight, and their lore. But it was swans I wished to paint this time, so swans I followed. They also echo the white of the stepmother/witch who becomes a white hare and also flies as an egret in the images.

I write in order to try to better understand a story, the layers, and the levels, and I hope also to move on old stories to a new generation. Sometimes tales become twisted to moralise. It disturbs me that often the women carry the blame for the actions of menfolk in stories. Stepmothers rarely fare well.

In fairy-tale studies, we often speak of how fairy-tale characters are depthless: they don’t necessarily show the full spectrum of human emotion as the story runs its course. But here, you have written a deeply emotional story, about love and loss and other aspects of human experience. What is your take on how emotions and fairy tales relate to one another?

I’m not a fan of having stories spelled out to me. I don’t like being told how to think of something. The best stories live in the geography of the mind for years and come to the surface sometimes when things happen, to maybe become a guide or a light. So I try to lay a trail of breadcrumbs through the wood that can be interpreted in different ways, depending on the experience of a reader.

In Andersen’s rendition of the tale, Eliza suffers a great deal alone. But in your version, you give her a faithful hound for a companion. Why? And why did you make some of the other changes as well, like giving the new Queen her own personality and motivations?

The hound is a curious creature. In the images, she lives a very long life and grows and shrinks. I wanted Eliza to have a companion, and the hound is her shadow, not a guide, but a kind of protector of the heart. The strangest thing happened the week after I painted Shadow. A friend came to my studio to tell me of a dog needing to be re-homed. I said, of course, I would take her. She is the beautiful Ivy, goddess of rock and stone, sleeping beside me now and the image of Shadow, as if I had painted her into being.

Written messages play a large role in your story: notes left in books or attached to the legs of doves. Why did you choose to utilize this extra level of textual encoding to convey meaning in your story?

Painted messages play an equal role between the reader and the story, if the reader cares to find them. I love the way the designer has given the text space, and turned the messages into handwriting.

The illustrations are gorgeous, and also convey an additional sense of meaning beyond the words in the book. What are some of your inspirations for these images, and how did you approach the challenge of conveying a fairy-tale feel?

Every story has its own challenge when it comes to illustration. In this book and its companion, East of the Sun, West of the Moon, I wanted the images to carry the story and allow the reader to slow, and breathe, and look. Some images decorate, others carry secrets. I also wanted the book to feel “far away and long ago.”

The reconciliation between Eliza and the prince is lengthy, more so than in the Andersen tale. How did you arrive at the words spoken between them, the apologies, and the forgiveness? And how do these things relate (if at all) to the message of the tale as a whole?

The ending of many stories troubles me. I don’t think I would be so forgiving of a prince who followed his duty to the point of allowing his loved to be placed on a pyre and burned to death. In writing the end, I tried to make Eliza walk away. Why, indeed, would you wish to marry someone who had been willing to offer you such a public and painful execution? He could have left her in the wood. She was happy there. But she refused to leave him, no matter how I tried. And she made him also a beautiful shirt, despite my better judgement. Perhaps she needed to teach me a lesson?

Folklore scholars debate whether silence in fairy tales is a curse or a blessing or a protest against patriarchal norms. While Eliza is silent, she is also gifted with the secrets from the hearts of the townspeople, but some of those secrets prove to be heavy burdens. Where do you ultimately stand on the issue of silence … does it help us, harm us, or perhaps a little bit of both?

For me writing is what George Mackay Brown called “the interrogation of silence.” Such a difficult thing to find, true silence. I live in a quiet place, where it is possible to hear the voices of birds, the wings of small creatures and on still nights the wings of bats. The world is full with noise and it does not play kindly to our mental health.

To seek silence as a choice is a good thing, I think. It allows time for thought, reflection. To fill all your day with the constant chatter of radio and television is soul destroying. Conversations with books can be had in silence.

Each of us has a voice and each person has the right to be heard, but so much of this is drowned out in celebrity, news, and game playing chatter. I would listen to the stories of migrant peoples, those whose own stories are far more powerful than the empty husks of politicians who would seek to silence them. The other kind of silence that comes from loneliness is not good.

So I would say, quietly, that silence is both. For me it is a necessary pleasure. I spent many hours knitting in silence while working on this book. These days I find that I need to listen, to learn to listen, to seek out stories from creatures not human, to learn to listen to birds, trees, rivers. To listen in the silence. To learn.

Jeana Jorgensen