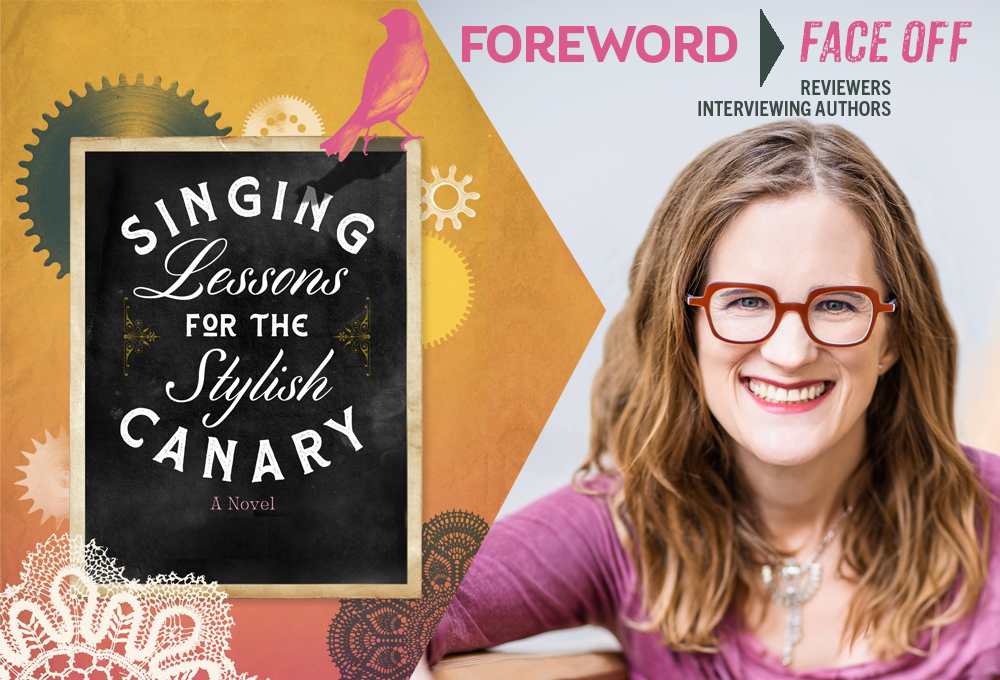

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Anne Schingler Interviews Laura Stanfill, Author of Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary

Book people come in all shapes and surprises, like Laura Stanfill, publisher of the acclaimed Forest Avenue Press and—what gives her gamechanger status—debut author of Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary, one of our favorite literary fiction titles of Foreword‘s March/April issue. We’re familiar with some accomplished multitaskers but Laura, you deserve some sleep, girl.

Enjoy this rollicking conversation.

Henri’s sincere belief that he can raise the dead becomes a source of major disruption to his life in Mireville. Still, the question of whether he is actually capable of miracles—indeed, of whether his father ever actually was–remains an open one. In a novel so laden with pronounced wonders, why did you elect to keep those answers ambiguous?

I grappled with this question for years, from various angles and with radically different results. Henri could raise the dead in some drafts; he failed bitterly in others. His ability is so big—bigger, arguably, than his father’s mythic gift—that when I made it wholly true, that piece of the storyline got too heavy. And in the drafts where Henri failed in every resurrection attempt, he never achieved the spark of confidence he needed to find his way.

From a thematic perspective, questioning each miracle allows me to dig into the idea of self-belief versus community groupthink. Which one is stronger: what the community says about a person, or what the person swears is true? Which perspective matters more? It’s easier for Mireville to credit Henri’s father—a firstborn, cis-gendered, white male—with bringing the sun to the village than to believe his strangely sensitive son might be able to resurrect the dead. The latter gift threatens the economic cycle in the village, as sons would never inherit their father’s workshops, and people who don’t fit in are scorned by the locals, not revered.

Besides, life is so often unclear, unfixed, cloudy. As children, we often believe in magic, unconditionally, even desperately, and that act of believing makes space in our hearts for joy, mystery, and humor. I wanted to replicate that kind of sparkly wonder by putting the maybe on the page.

Can you please tell us a little about what’s behind your fascination with serinettes, which undergird a considerable portion of the magic and fortunate turns of your book?

Serinettes are high-pitched barrel organs that were used to train songbirds to sing popular songs. They sound like a cross between birdsong and piccolos. Men made serinettes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, primarily in Mirecourt, France, which I fictionalized as Mireville in Singing Lessons. Serinette buyers—because learning about the making led to curiosity about the customers—were primarily wealthy women in the United States who wanted to win canary contests.

I fell in love with the surprise of this piece of history, then became obsessed with the economic disparity between makers and buyers and the absurdity of a business existing to train a bird away from its natural voice. What does the serinette tell us about that time in history? About who gets to sing—or speak—their truths? I wanted to explore those questions in fiction.

But I didn’t start out to write about serinettes. I found the instrument in a glossary while thinking about the collecting mentality and preserving music history. Throughout my childhood, I attended mechanical music conventions and street organ festivals. While my peers listened to popular songs on the radio and made mix tapes, I listened to music boxes, learned to pull the stops on street organs, and pressed my favorite song buttons on the family juke box. For a long time, I didn’t see the whimsy or charm in my upbringing, only how different it was from my peers’ lives. In casting around for material for a new novel, though, I found myself savoring my childhood and thinking about the makers of these mechanical objects—what their childhoods would have been like. And a mechanical work of art, one with a crank, offers a great metaphor for the act of living. Moving forward to the next tune or playing the same song over and over again, stuck in a place or an emotional rut. You can’t rewind.

The women in your novel are boundary-breakers: they defy their husbands, they make their own ways in periods that are often hostile to women’s independence, they stand up for their children against toxic demands and expectations, and they excel in trades that are supposed to be the purview of their fathers and brothers. The men, meanwhile, are simultaneously community heroes and afflicted with deep self-doubt that the women in their lives seem to evade. Is this separation between society’s understandings of people and their internal lives a consequence of the period in which your novel takes place, or is something else at play there?

As a neurodivergent author, I wanted to explore how people whose brains work differently can bend social rules (not always intentionally), and how over time, acts of defiance create space in a society for real change. Georges, Henri’s father, is less rigid than his father, and Henri exists even further outside that strict hierarchy. In thinking about Henri’s influences—who enables him to become, well, himself—I realized I could give the women storylines and space to be secretly revolutionary, to act on their hearts by going around the men in their lives. Henri watches them and realizes he needs to take risks to be himself, just like his mother and grandmother have.

Technique-wise, Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things taught me that a book could be set in the past without sacrificing modern sensibilities. That idea became the heartbeat thrumming beneath every sentence of Singing Lessons. How could I get the nineteenth century on the page without filling the manuscript with era-appropriate trauma and toxicity? The answer, for me, was to examine gender roles and make quiet rebellion a theme. I didn’t want to write a novel full of silent, obedient women, although it’s likely that many of the families who lived in the real village of Mirecourt kept those traditions and boundaries. Small acts of defiance and rebellion can add up, though, and that’s the story I chose to tell.

Since we’re speaking about your alluring characterizations, I’m still a bit enraptured by Delia, who breaks every rule to secure and keep her odd high society position in New York. I found myself wanting more of her story. Do you have plans for a companion novel or story, or are there any stories about her that did not make it to the page?

Delia showed up with a complete backstory and personality and absolutely no regard for the role I had planned for her to play. I had to adjust the novel to flow around her—much to my chagrin. I probably would have finished the book in a shorter time if she hadn’t been so obstinate.

I had initially intended for Delia to be the dragon in the hero’s journey, a fierce force who magnified the themes and social pressures in the rest of the novel. Don’t you think someone who trains birds away from their natural voices would make a great villain? Alas, she’s strong-willed and right from the start, she annoys her neighbors instead of participating in the restrictive social fabric (as I had intended). As I wrote new swaths of text and cut out countless characters over my decade-plus of working on this book, Delia clung to the page and ultimately became the key to nailing the final third of the novel. I had to reconceive the arc of the novel to suit her, because she wouldn’t budge.

As far as extra material, I have so much more on Delia—cut scenes, more backstory, longer aviary descriptions, a deeper investigation into the tragedy of Scheele’s Green, and a partial draft of a sequel that’s full of birds and ghosts. I also wrote a companion short story, “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” which was published in VoiceCatcher years ago, but is now out of print. It’s about a canary named Buster who performs at a dinner party. The hostess was a precursor to Delia—mourning her husband, living outside the expected boundaries, thinking extravagant thoughts, feeling lonely. They have different names, but Mrs. Percy Mallaby in the story feels like she was the seed out of which Delia grew into herself.

Readers can often forget that the novels they lose themselves in are the products of years of work, from the spark of the concept through to drafts and editing and refinement. Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary is your debut—and is the product of such meticulous care and time. From the writer’s and publisher’s side of beautiful works, what encouragement can you offer to those who are in the earlier stages of their projects?

One of the best parts of being a publisher is getting to encourage writers. Here are a few tidbits from a lifetime of writing manuscripts and a decade of publishing others’ works.

On voice: If you know what you want your manuscript to sound like, and you’re not there yet, keep going—even if your critique partners or friends don’t quite get it, and especially if your book doesn’t sound like anything else out there. If your vision is true, and you put in the time, you will find a way to get the story down. Be patient with yourself. Let yourself play and see what happens.

On identity: This may apply more to debut authors than seasoned ones, but when I started working on Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary, I hadn’t delved into all my personal treasure-boxes of story, or really let myself understand what I wanted to say. As a result, those early drafts meandered and didn’t have a strong sense of purpose. If you can gently pull the curtains away from your self-belief, and really look at what you want to say, you’ll find your manuscript has clarity and spark. And that will set it apart from everyone else’s books. If you’re feeling lost in a draft, ask: Why is this my story to tell? What am I really saying?

On rejection: Not every book is for every reader; the same goes for publishing, but sometimes a no knocks that sense out of us, because it feels so crushing. You must steel your nerves when you’re on submission, whether you’re seeking an agent, a small press, or a home for an excerpt or a companion essay. What an outside person says about the work doesn’t supersede your experience of writing. The time you’ve spent on the page, getting deeper into the work, is what matters. Create a ritual around rejections, whether that’s submitting to the next place, lighting a candle, or giving yourself a hearty pat on the back for putting yourself out there. Then get back to work.

You are the founder and publisher of Forest Avenue Press, which publishes brilliant and daring cross-genre work—space that Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary occupies. But you published with Lanternfish Press instead of your own. While their stylishness and vision also befits a book as singular and wonderful as yours, we wondered what was behind that decision? And what was it like working on the author’s side, rather than on the publisher’s side?

Thank you so much for the kind words. While Singing Lessons matches the sensibilities of my press, I knew I wanted someone else to take the lead on marketing and promotion and the thousands of small decisions that go into the making of a book. I’m much more comfortable promoting other writers than putting myself in the spotlight. And having a publisher means there’s a buffer between me, a first-time author, and the outside world of reviewers and critics.

Working with the fabulous Lanternfish team has meant editorial guidance, a dedicated in-house publicist, and direct support from the publisher. It’s been a great experience and I feel so lucky.

Michelle Anne Schingler