It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

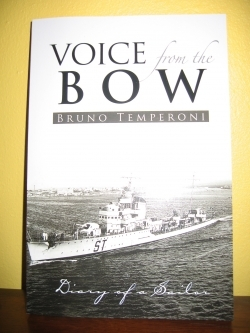

Voice from the Bow

Diary of a Sailor

And so the war came!

Bruno Temperoni was in his mid fifties when he wrote those words in a preface to the publication of a diary he kept as a callow twenty-year-old sailor, in the Italian Royal Navy, during World War II. The exclamation point at the end of the sentence serves to illustrate his reaction to the carefree, mischievous innocence he barely recognized, as he recalled the youthful adventure that shaped his life.

As the diary retraces Bruno’s at-sea service, from 1938 to 1940, it might serve as a universal coming-of-age story. And therein rests its appeal, despite a sometimes tedious recitation of daily events.

Early on there is a reminder of the nationalism, which fuels so many conflicts, in the words of a lieutenant’s speech to assembled sailors. “The enemies of Italy have prepared a large mine and are getting ready to light the fuse,” he said. “Only one man is taking care of Europe to grab it out of their hands. That man is the Duce.”

But politics and worldly affairs are only of passing interest to the sailors. There are more pressing concerns. For instance, there is, in a Naples brothel, the lovely Evelina with the heart of gold. She told Temperoni, “You are not like the others,” and so they met in the sunshine the next day, and for several days thereafter, until she told him she was leaving. “I don’t want you thinking of me in other places like this one,” she told him. “Maybe I will retire. Now, I cannot stand this life anymore.” He was both sad and happy. “Farewell Evelina,” he wrote. “I do not want to judge you.”

A short time later, back on board his destroyer, conflict is imminent with the British, whom the Italian sailors call “chocolate eaters.” “I pray to God our Lord that he may save us from the tragedy of war,” Temperoni confides to his diary; but his prayer is not answered. A British submarine is sunk in the first encounter, and, although he urges God to “welcome to your reign the brave enemy crew who died for its homeland,” there is clapping and cheering.

The war grinds on, with the horror of attack and counter attack. A good friend is killed and Temperoni embraces an old Roman adage regarding enemies in battle: “Your death is my life.”

Italy lost the war, of course, and eventually Temperoni made it home. He worked in the family furniture factory and won a number of prizes as an artist and designer. He died in 1995; the last words he wrote in an afterword to the diary was for God to bless all those “who have died in vain at sea.”

Reviewed by

Tom Bevier

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.