It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

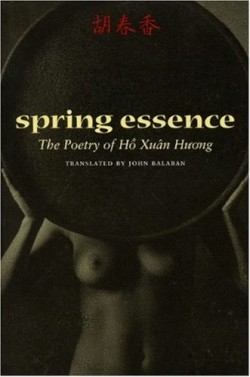

Spring Essence

The Poetry of Ho Xun Huong

A conscientious objector, translator Balaban; an eighteenth century concubine and poet, Ho Xuân Huong; and a linguist from New York University, Dr. Ngô Thanh Nhà n; have created a book rife with firsts. Like many groundbreaking, nationalistic writers, Huong wrote her poetry in the vernacular of her people, the Vietnamese. Through the efforts of Nhà n, the original ideographic script, Nom, has been replicated for the first time using moveable type. Balaban discovered the writer while doing humanitarian work during the Vietnam War. Most scholars believe that Huong was a concubine who lived at the end of the second Le Dynasty, a period of social and political unrest. From this chaotic daily life, Huong drew her subjects of patriarchy, sexuality, and power.

Most of her poems work in two distinct ways. First, they fulfil Western expectations for Asian poetry. They have an elegant simplicity in wording and structure, a longing for things eternal, and the suggestion that this writing is merely part of an ongoing poetic conversation. She writes in “Autumn Landscape,”

Drop by drop rain slaps the banana leaves.

Praise whoever sketched this desolate scene:

the lush, dark canopies of the gnarled trees,

the long river, sliding smooth and white.

On the other hand, they also read powerfully as sexual poems, employing sensual double entendre. Because the book is formatted to show, over a double-page spread, the poems written in the original Nom, modern Vietnamese and the translated English, a knowledgeable reader can derive even more pleasure from the word play created by changes in the tonal language. The meaning of Vietnamese words changes based on tonal inflection; Huong exploits this linguistic trait, and Balaban clues readers in through his careful and informative endnotes.

Huong resents the concubine’s fate, shows a profound awareness of women’s fate, and acknowledges sexual joy and its loss through aging and societal response to that process. In “Confession (I),” she writes:

I haven’t shaken grief’s rattle, yet it clatters.

I haven’t rung sorrow’s bell, though it tolls.

Their noise only drags me down, angry

with a fate that says I am much too bold.

Men of talent, learned men, where are you?

Am I supposed to walk as if stooped and old?

This collection places readers in two triumvirates; one of history, sexuality, and literature; the other of poet, translator, and linguist. The finished product is an interdisciplinary experience few books can replicate.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.