It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

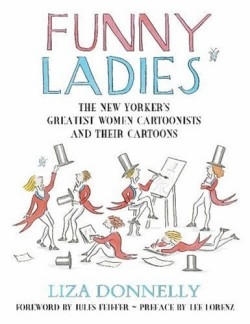

Funny Ladies

The New Yorker's Greatest Women Cartoonists and their Cartoons

For decades, the weekly New Yorker has been renowned for its “drawings”—the cartoons that reduce complex social and political situations to humorous line-drawing evaluations—as well as for its superlative writing. Some of the magazine’s cartoonists have become equally renowned—William Steig, Charles Addams, James Thurber. Less well known are the many women who have made, and still make, cartoons for the magazine, since its inception in 1925.

The author—having herself been a New Yorker cartoonist for twenty-two years, as well as having written and illustrated children’s books and edited four previous collections of cartoons—offers an insightful look at the magazine’s history of women cartoonists. Looking at the artists’ work through the lens of how their pioneering efforts led the women’s movement, she divides this lively yet serious volume into seven chronological sections, from “The Early Innovators (1925—1930)” to “The Future (1997—2005).”

The magazine’s founder, Harold Ross, was a traditional man until he married Jane Grant, who kept her own name and worked alongside him in creating the magazine. He grew courageous enough to hire women as writers and cartoonists, and to encourage them to provide material in their own voices, even if the result was controversial in its brand-new feminism. New Yorker cartoon women have always smoked cigarettes and talked openly about sex, but the subjects of the early cartoons were usually still women’s concerns—marriage and children, not business.

Barbara Shermund’s cartoons appeared beginning in 1926; Donnelly says “She drew mostly about the New Woman, demonstrating an understanding of her newfound independence while not being afraid to poke fun at her.” In one of Shermund’s drawings, a young woman at a backyard tea party says to her friends, “Yes, Jane was stunning. But she’s married now.”

Using letters, photographs, and other archival material as well as reproductions of cartoons, Donnelly carries the reader through the Great Depression, with its anti-feminist backlash of humor that tended to deprecate women; World War II, with its perceptive depictions of women factory workers and military girls putting on makeup; the 1950s and ’60s (which the author calls “a somewhat bland period for The New Yorker”); and the influx of powerful new female cartoonists in the last thirty years.

Donnelly provides sensitive biographies, detailing each woman’s substantial artistic background, as well as a history of the magazine as intimate as if she herself had been “art boy” at one of the famous Tuesday art meetings, “the unofficial day to bring in cartoons.” With scholarly yet animated writing and witty sidebars, she describes the reign of several New Yorker editors, and the evolution of the role of women cartoonists.

Donnelly’s own cartoons are dynamic and clever, and she offers philosophical musings on the role of cartoons in literature, as well as her opinion about what makes a cartoon work. She asserts that a good cartoon “should not be forced, unless the forced nature is part of the joke, as in an obvious pun.” In one such commentary, Donnelly depicts a waiter approaching a group of diners with a platter on which crouches a man with a briefcase; the waiter asks, “Who ordered the special prosecutor?” The cartoonist was playing against the atmosphere of the time when, as the author says, “special prosecutors were being frequently ordered for investigations. This is pure play on words, with the extra added visual humor of the prosecutor sitting on the tray.”

During Donnelly’s generation, the magazine acquired the talent of Nurit Karlin, whose cartoons “made the viewer see life in a deeper way despite a deceptively sweet comment,” exemplified by her drawing of two peace doves playing tug-of-war with an olive branch. Roz Chast, who wrote, “I didn’t want to be a ‘woman cartoonist,’ I just wanted to be a cartoonist,” joined the magazine around the same time. Chast’s drawings —like “The Velcros at Home” and “Passive Aggressive Birthday Gifts (For When You Don’t Like the Kid … or the Parents)”—feature her signature tiny details.

“What has changed over the course of The New Yorker‘s eighty years,” says Donnelly, “is that women now draw cartoons about anything, because women are doing (almost) everything.” It may be too late for Alice Harvey, Helen Hokinson, and Mary Petty to become household names as famous cartoonists, but Donnelly’s book may help promote the names of Roz Chast, Anne McCarthy, and Victoria Roberts.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.