They Believe: SETI's Search for Extraterristrial Life

Human beings, in times of need, sometimes look to the skies for rescue. While once people presumed that delivery would come via a deity, a more recent kind of faith has placed our hope in the hands of beings just as unseen: extraterrestrials.

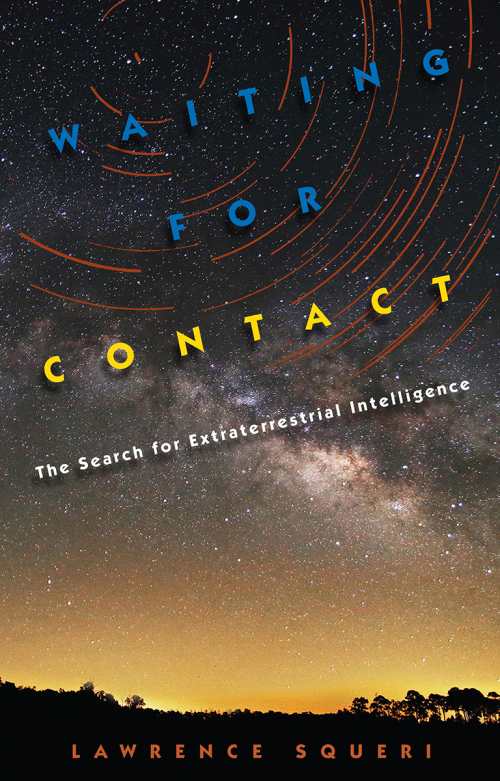

Lawrence Squeri’s fascinating new examination of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) movement, Waiting for Contact, from the University Press of Florida, reveals that the fervor of its originators did, indeed, have much in common with religious impulses; though they were scientists, they found themselves absorbed with the unknown, postulating and dreaming beyond that which could be rationally discerned. His is a revealing and thoughtful look at star-centric intersections of science and belief.

You reveal that the search for extraterrestrial life is very often about seeking justification for our own ideas—about our origins; or for ideologies–from the stars. Do you think any of the SETI pioneers you mentioned were particularly good at navigating around such temptations, or do you think that’s an inherent part of speculating about the unknown?

Lawrence Squeri. 'SETI is like religion; it produces believers and skeptics.'

The two SETI scientists who were particularly good at navigating around the temptation of seeking extraterrestrial validation were Ronald Bracewell and Philip Morrison. Whatever their private thoughts were, Bracewell and Morrison were measured in their public statements. In responding to the inevitable question of extraterrestrial motivation for contact, they did not state a missionary impulse to help humanity. They instead envisioned ETs as anthropologists who are curious about us for the same reason western anthropologists study non-western peoples.

Morrison had no illusions about instant knowledge coming from the stars. He was well aware that scholars spent decades trying to decipher the writings of ancient civilizations, and some ancient scripts such as the Minoan and the Etruscan remain mysterious. Morrison predicted decades, if not centuries, of hard work to make sense of an extraterrestrial communication.

What prompted you to write this expose of SETI? Were you particularly surprised by any details uncovered in the course of your research?

The science fiction movies I watched in my youth made me wonder whether we are the only intelligent creatures in the universe. A search for extraterrestrials would require a grounding in science, but I was drawn to the study of history. At some point in my life, I realized that I would never search for extraterrestrials and that I should instead study the scientists who look for them. Hence, I wrote a history of SETI.

My big surprise was finding out that simple curiosity did not explain the motivations of the SETI people. They were hoping to learn from extraterrestrials. I learned that curiosity itself will not motivate people to do a search. There must be some sort of payoff from contact. After all, as I explain in the book, it was Gold, God, and Glory that motivated Columbus and the other explorers of Europe’s Age of Discovery. Curiosity ran a distant fourth.

Can you tell us about the experience of working with the University Press of Florida to bring Waiting for Contact to press?

The University Press of Florida was perceptive and supportive. I received quick responses to my emails and was given good advice. I’ll give one example. My original title was Waiting for ET: The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. The Press pointed out that “ET” might imply a reference to the Steven Spielberg movie. It was suggested that I substitute “contact” for “ET” and I did so, thus improving the book’s title.

In addition, one of the three readers the University Press of Florida chose to evaluate my manuscript was a SETI true believer who disliked my argument. I believe that I did a good job in answering this reader’s objections. The Press’s editor accepted my thesis that SETI is like religion; it produces believers and skeptics. Nevertheless, this reader sharpened my thinking and spotted minor errors. He/she strengthened the final text.

Your book talks a lot about what could possibly be gained from contact with extraterrestrial beings. What, if anything, do extraterrestrials stand to gain from interacting with us?

Extraterrestrials may be like us, a mixture of vices and virtues, but with a key difference. Their virtues and vices may not match ours. For example, a SETI truism has been that superior extraterrestrials have mastered their versions of lethal technology. Survivors of an extraterrestrial nuclear winter might find out that humans used atomic weapons only once, over seventy years ago, and they have not used them since. Instead of our learning the arts of peace from them, they might want lessons from us. I know what I wrote here would shock Carl Sagan, if he were alive. He was so pessimistic about humanity’s future that he could not imagine human superiority in the arts of peace. But we must be open to all possibilities, when faced with the unknown.

One fallacy in the SETI narrative, which I ignore in the book, is the assumption that extraterrestrial progress in technology matches humanity’s. By human standards, extraterrestrials may be backward in one area and advanced in another. For example, it may be that the extraterrestrials who contact us have a superior physics that makes for great radio telescopes but still use animals for land transport. It may be that extraterrestrials are healthy but do nothing to prolong their lives, accepting death as natural. The human practice of using technology and knowledge to prolong life might surprise them. Once we become open to the possibility that ETs may not be technologically superior across the board, we can and must consider that we have something to teach.

Hopefully, we do not corrupt them. We might introduce alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs to the worlds of outer space and extraterrestrials might be grateful or curse us forever. Who knows?

What projects are you working on next?

Apart from my interests in space, honed by science fiction, I have always been intrigued by the Italian-American world of my youth. My parents were Italian immigrants from the mountains of Parma and they never spoke English at home. They only socialized with relatives and friends who came from the same part of Italy. Although they lived in New York City, became citizens, and had no thoughts of returning to Parma, their minds and attitudes were locked in that distant world where they grew up. Although I will always retain my interest in SETI and extraterrestrials, my next project will be a history of Italian Americans. Maybe, in retirement, I am returning to my roots.

You mention figures, from astronomers and astrophysicists to science fiction writers and politicians, who in some way impacted SETI. If you could sit down to dinner with two of these people, who would you choose, and what would you talk about?

Yuri Milner, the Russian venture capitalist who has made a fortune in Silicon Valley, recently donated $100 million to the SETI movement. Yuri Milner’s donation occurred when I was finishing the manuscript. SETI seemed in decline and the book’s ending was a little downbeat. Milner’s donation allowed a new, upbeat ending to the final chapter. His public statements for supporting SETI do not go beyond curiosity. Unlike the earlier SETI people, he has not mentioned (in public, at least) the benefits accruing from contact. I suspect something stronger than mere curiosity motivates Milner’s SETI passion because his other claim to fame, apart from being rich, is his creation of the Breakthrough Prizes in Life Sciences, Fundamental Physics, and Mathematics. Could the promotion of SETI be another means to expand human knowledge? Could Milner, like the SETI pioneers, believe in human enhancement from contact? If so, what does he believe humanity might gain? Unlike Carl Sagan, who spoke his mind, Milner seems reserved in his public statements. I would ask him to talk about any subject he wishes.

Carl Sagan died before the era of Active SETI, the sending of radio messages into outer space in the hope that ETs might listen and respond. Active SETI has divided the SETI community, and I would ask Sagan for his opinion. Would he believe that we should lie low in case outer space contains hostile forces, or would he continue to believe in benevolence among advanced extraterrestrials? I would also ask Sagan what could be done to make the public (and therefore the federal government) increase its interest in space.

Michelle Anne Schingler, a major Carl Sagan fangirl, is the managing editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler