The Art of Baron Yoshimoto

Pablo Picasso is quoted as saying, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” Many of us may recall answering the standard elementary school question of “What do you want to be when you grow up?” with vocations such as astronaut, ballerina, veterinarian, international pop sensation, fireman, or, indeed, artist. As children, we perceive anything and everything as being within reach if only we have the courage to aim for it, but, as we grow up, practicality often demands we shelve our passions.

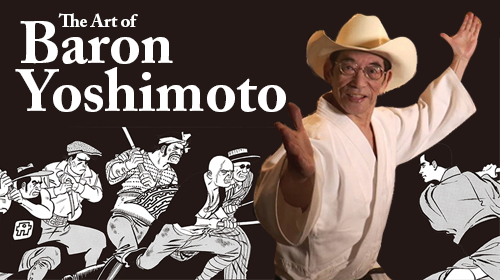

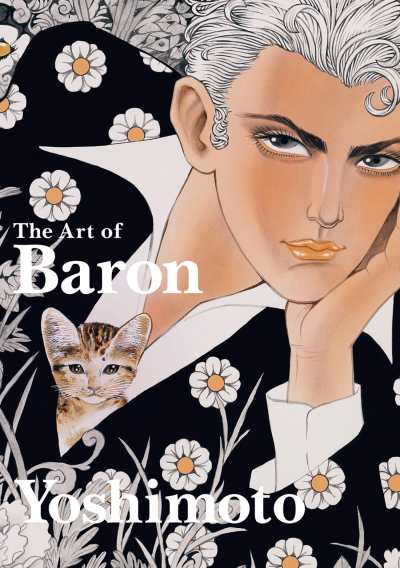

This, however, is a false choice, and no one better exemplifies that fact than Baron Yoshimoto, a seventy-nine-year-old manga illustrator and painter who has enjoyed an evolving sixty-year career—and still finds time to don his ten-gallon hat and hit the disco. The Art of Baron Yoshimoto is an attempt to track this evolution, following Yoshimoto from Gekiga to his most recent heavenly bodies paintings and live-drawing events. With influences ranging from Asian mythology to America’s Wild West, there is something to entice the artist within us all.

Intrigued by Baron Yoshimoto’s joyful persona and venerable career, we worked with PIE International to set up an interview. We are certain his answers will surprise and inspire you as well.

Some of your earlier work included in the book depicts scenes from the American Wild West, including gunslinging cowboys and a dynamic interpretation of Custer’s Last Stand. You’ve also made a ten-gallon hat something of a signature accessory. What sparked this fascination with that period of history?

I was into American Wild West since I was a child. Western comics and manga had wilderness, horses, small towns, gunfights, poker, good-looking girls, and a simple story line. What intrigued me was the mix of those factors and the cowboys’ way of life. The frontier spirit symbolized by items such as the Colt Single Action Army revolver was interesting.

In an interview featured at the end of the book, you say that you “can’t draw manga carelessly or play carelessly.” That struck us as sound life advice, but also got us wondering: what are some of your favorite “play” activities when you’re not working on manga or painting?

In a society full of discomfort and irrationality the only freedom we can obtain is through play activity. Creating art gives me the most pleasure but I can’t stress enough the importance of play activity which makes your body flexible. For me, that meant indulging myself in dancing at discos and nightclubs. Play activity gives me power to move on.

In the eighties, you left Japan and moved to Los Angeles to both enhance your visibility in America and reconnect with your passion for painting. Considering you were at the height of your fame as a manga artist in Japan at the time, what prompted the sudden move? What was the reaction among your fans and critics in Japan when you decided to leave?

I have always been a big fan of American culture in general such as movies and music, not to mention comics. For example, I can’t stop projecting myself to the teenagers in the movie American Graffiti because they were of the same generation. After starting my career as a manga artist, I went to the US to do research on the Watts Riots, which happened in 1965, and hippie culture.

The biggest reason that I went to the US was that I thought I could find the greatest freedom if I was able to work there. Other manga artists and editors tried to stop me by saying, “Many fans are waiting for your manga,” but I didn’t change my mind. I might have been the first Japanese who worked for Marvel. It was a tough time when I was presenting my work to publishers in the US just by myself and not through Japanese publishers. But I was fortunate to meet Stan Lee, Rocky Aoki (founder of Japanese restaurant chain Benihana), and Larry Hama (writer of G.I. Joe) who gave me inspiration and taught me how to have fun in the US.

The timeline of your career included in the collection mentions that your name was changed without your knowledge when you made your commercial magazine debut, and that you were not initially happy with that decision. If you could have selected your own pseudonym, what would you have chosen? Or, would you have preferred to continue working under your given name?

In recent years, I have been using my other pseudonym, Ryu Manji, for my painting works—which I named myself thirty years ago—while not revealing the name Baron Yoshimoto. But as a manga artist, I guess I would have liked to keep using my given name rather than my pseudonyms. On a side note, recently I have learnt that Hokusai, the great Ukiyo-e artist, used a pseudonym, Manji, in his late years, which made me feel very close to him.

You deal with many different subjects in your paintings, but heavenly bodies—nude human forms often floating in intricate, celestial patterns—are a recurring theme. Given Japan’s historical restrictions on explicit content, did you ever receive any negative reactions to these works? Do you feel your time in America early in your painting career may have influenced your freedom with this subject matter in some ways?

From olden times, heavenly nymphs were often depicted in Asian mythologies. Usually they wore thin raiment but I wanted to show them as mystical and beautiful physical bodies, free from the idea that they should be wearing something. That is when I came up with the idea of “Hi-sho-en” (heavenly nymph who wore an aura). And if there was a heavenly nymph, there should also be a celestial man and a child.

As my imagination expanded, my imaginary inner world “Godpia” (the biosphere of space) became bigger and bigger. The story starts with two heavenly nymphs who have committed a crime and were sent down to the earth. At first I was planning to start a manga series but describing the story with a painting became entertaining for me and here I am now.

I have never been judged negatively with my nude human body paintings. In general, people say that nude artwork is hard to sell because not everyone has a space for it in their homes, but I have never really thought about this—maybe because I didn’t care much about selling my art until now.

Finally, you have recently collaborated on a few occasions with renowned manga artist Katsuya Terada. We were wondering: if you could choose any other artist—manga artist, Renaissance painter, or otherwise—to collaborate with, who would you want to team up with?

I would say Michelangelo. The new painting which I’m working on right now is inspired by “The Creation of Adam.” I would definitely want to collaborate with him.

Baron Yoshimoto, The Art of Baron Yoshimoto, 978-4-75625171-8, PIE International, http://pie.co.jp/english/

Danielle Ballantyne