Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Edmund Stump, Author of Otherworldly Antarctica

“The stillness. Ah, the stillness. When there is absolutely no movement in the wind, and you are beyond the hum of motors, it becomes a tangible presence. If you are still and not breathing, you hear the blood pulsing in your ears.’’ —Edmund Stump

We’re headed to Antarctica today, land of forbidding seas, rock, and ice—one that increasingly appears on bucket lists of average joes and janes from Cleveland and other average places. But not so long ago, only a few research parties made the long journey each year to work from hastily built field stations. And should those teams of scientists stay over the polar winter they knew full well that they had almost no chance of rescue should an emergency arise.

Here’s a quick story from the British Medical Journal about those early days.

In late April of 1961, with his team of eleven men at a newly built Russian base camp at Antarctica’s Schirmacher Oasis, 27-year-old Leonid Rogozov found himself suffering from abdominal pain, weakness, and nausea. Over a few days, he continued to worsen and soon realized he had the classic symptoms of appendicitis. He needed an operation.

Here’s the kicker: Leonid was the camp physician; his only chance for survival required that he grab a scalpel and operate on himself—which he did for nearly two hours with one of his comrades holding up a mirror and his spirits.

Here’s a passage from his journal:

“I worked without gloves. It was hard to see. The mirror helps, but it also hinders—after all, it’s showing things backwards. I work mainly by touch. The bleeding is quite heavy, but I take my time … Opening the peritoneum, I injured the blind gut and had to sew it up. Suddenly it flashed through my mind: there are more injuries here and I didn’t notice them … I grow weaker and weaker, my head starts to spin. Every 4-5 minutes I rest for 20-25 seconds. Finally, here it is, the cursed appendage! With horror I notice the dark stain at its base. That means just a day longer and it would have burst and … At the worst moment of removing the appendix I flagged: my heart seized up and noticeably slowed; my hands felt like rubber. Well, I thought, it’s going to end badly. And all that was left was removing the appendix … And then I realised that, basically, I was already saved.”

Within two weeks, he returned to regular duty. He lived another forty years and died in St. Petersburg in 2000.

Edmund Stump’s Otherworldly Antarctica earned a starred review from Rachel Jagareski in Foreword‘s March/April issue. We’re excited to share their conversation.

I understand that scientific opportunities to spend time in Antarctica are extremely limited. How did you manage to score thirteen field seasons there?

The first time someone goes to Antarctica it is typically as a member of someone else’s party. Mine was as a PhD grad student on an expedition to the Transantarctic Mountains funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Ohio State University. When I got back from that first season, I was awestruck by the place and had a single, unrelenting goal—to return to that alien land of ice and rock. I argued that I didn’t have enough data for a dissertation from one season, and that was true. The Institute of Polar Studies (today’s Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center) was extremely supportive and I was awarded my own grant as a grad student in 1974. That was before peer review was initiated at NSF. My grant was at the discretion of the program manager, to whom I am eternally grateful. I am sure that this grant landed me the job at Arizona State University, where I was able to keep the research ball rolling throughout my career.

Yes, the opportunities to spend time in Antarctica are extremely limited these days. If I were starting in the research game today, I doubt that I would make it. Antarctic Science isn’t alone in this. Across the board in the sciences, the competition for grants has grown ever more intense, with ever diminishing success ratios for proposals. We have spawned increasing numbers of exceptional PhDs for generations, and most want to have a research career.

How did the stillness and absence of life in the regions you studied affect you? Did your perceptions of time shift?

I was totally at ease with the absence of life. The wild ice and rock sustained me. I’m a geologist, after all.

The stillness. Ah, the stillness. When there is absolutely no movement in the wind, and you are beyond the hum of motors, it becomes a tangible presence. If you are still and not breathing, you hear the blood pulsing in your ears.

On the time-shift question, during each of my remote field seasons (party of four, snowmobiles, sleds, tents) we tended to shift off a 24-hour clock. The sun is always above the horizon during the austral summer in Antarctica. Some days we would be out from camp twelve or more hours, mapping and collecting. Then maybe three hours shaking down samples, cooking dinner, eating it, and going to bed. Sleep nine or so hours. Then another three hours rising, eating breakfast, and hitting the trail. Add this up and it is twenty seven hours or more on a long day. That we free cycled was to the chagrin of the radio operators at McMurdo Station when we didn’t report in at the scheduled 8:30 a.m. roll call for all remote field parties, since we were likely on the slopes or sleeping.

What effects of climate change did you witness in this polar region over the course of your four decades of study?

I personally haven’t witnessed any since my work was in the interior and the inertia of this region’s frigid ice is huge. The coastal regions are where the action is. The Antarctic Peninsula has recorded the greatest increase in annual temperature of anywhere on Earth. The glaciologists that study Pine Island Bay have sent warnings of a possibly retreating grounding line beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the consequences of accelerated melting and sea level rise. To me the most alarming recent change is the sharp decrease of winter sea ice around Antarctica.

Can you elaborate on your collaborations with artist Marlene Hill Donnelly regarding her illustrations adding geographic scale and interesting scientific facts to your captivating photographs?

Bringing Marlene Hill Donnelly into the project was an idea of my editor, Joe Calamia. He felt that there needed to be some sort of scale so that the immensity of the Antarctic features could be appreciated by readers. I fully concurred. The notion was that Marlene’s watercolors would give the appearance of pages from a field sketch pad. I am very happy with the results. It was fun coming up with the scales: a herd of giraffes, the Empire State building with King Kong hanging from the top, the whole of Manhattan Island.

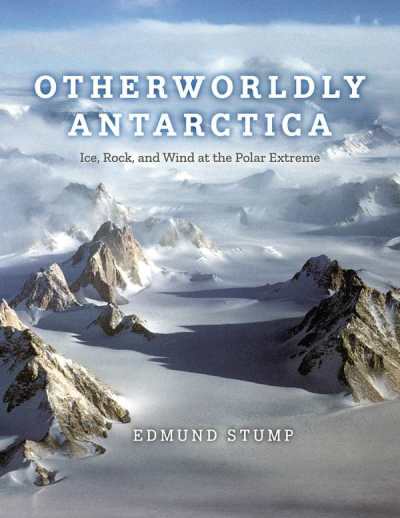

Your photographs wrest so much emotion, pattern, color, and texture from the Antarctic landscape. What, if any, kind of photographic training have you had?

Thanks for the compliment. I’ve had no training in photography, no class, no mentor, no book. I love Nature profoundly and respond to it through my photos. I shot film, Kodachrome 25, until the 2010–11 field season when I bought a digital camera. With a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera what you see is what you get. Add a zoom lens and the possibilities are limitless. If asked, the only advice I ever give someone about photography is look into the corners of the frame before clicking the shutter.

What do you miss most about Antarctica? Any plans for another trip?

What I miss most about Antarctica is the place itself (out away from stations and people), the stark, lifeless landscapes, the vast panoramas of ice and rock, the stillness, Nature unto itself.

I retired from teaching and research in 2014. However, I would love to serve as a lecturer on another Antarctic cruise. No plans yet. Anyone out there listening?

Rachel Jagareski