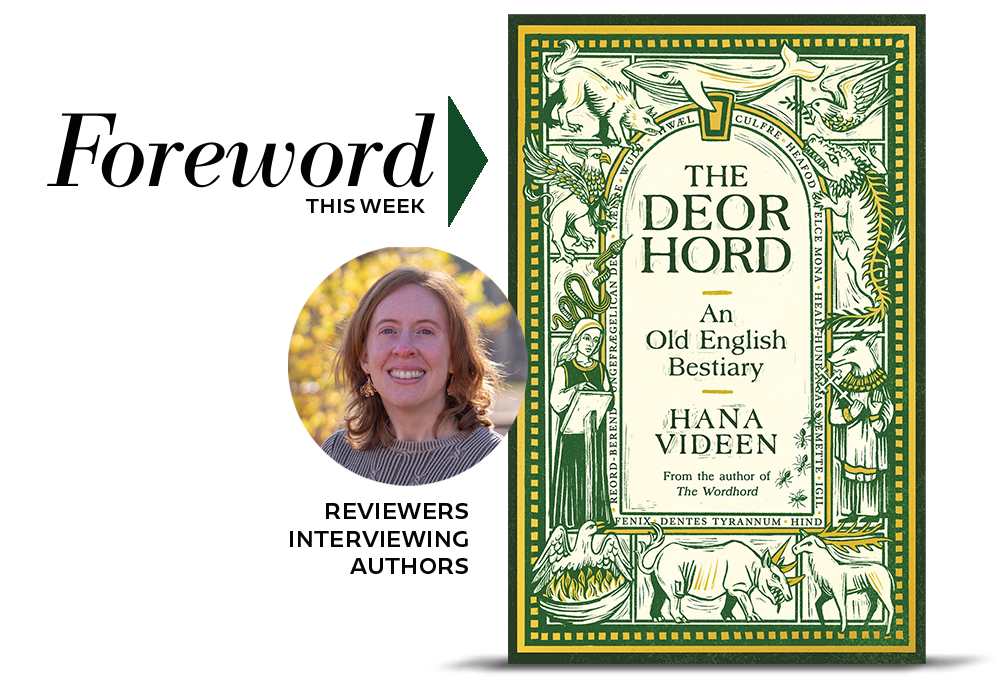

Interview with Medievalist Hana Videen, Author of The Deorhord: An Old English Bestiary

If your grandmother is eighty years old and when she was a child of five met a woman who was eighty and when that woman was five met a man who was ninety and when he was five met a woman who was a hundred and continuing back, consider the astounding fact that it only takes twenty one more people to reach the time of Hadrian at the height of the Roman Empire. In other words, you know somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody—just a few more times of this—who might have drank Falanghina from the slopes of Vesuvius with a Roman Emperor. Peer back a couple more lifetimes and you’ll arrive at the time of Jesus. Crazy, isn’t it, how close we really are to anyone, anytime?

Here’s another universe-expanding exercise: Imagine yourself with a set of incredibly powerful binoculars looking at the Earth from a planet 2000 light years away. What you’d be seeing through those binocs—in real time—is the torchlight and bonfires and sunlight reflecting off our planet from the year 1 CE (again the time of the Romans and Jesus). That’s how long it takes (in one light year light travels six trillion miles) for those images from Earth to reach you on Planet X. So yes, in essence, you’d be looking back in time but that’s simply how light and space and time work.

Forgive us for straying off topic today—we thought you might like a break from the news of the day. That said, today’s interview takes us back just five or six personal relationships to medieval times and showcases how our current perception of the animal world came to be.

Here’s a link to Jeana Jorgensen’s review of The Deorhord from Foreword’s March/April issue.

Why did you decide on the categories of ordinary, extraordinary good, bad, and baffling animals?

When I was choosing animals for the book, I didn’t have those categories in mind—I was just picking the critters I thought were interesting or that featured prominently in Old English texts. But I had so many animals it made sense to try to group them. The good and bad categories came first, since there are so many creatures in medieval bestiaries that clearly align with either Christ or Satan. The ordinary and extraordinary categories came next. You find a lot of extraordinary creatures in travel narratives, like Alexander the Great’s Letter to Aristotle and Wonders of the East. (The word in Old English is un-gefrægelic: “extraordinary” or “unheard of.”) Finally, there were the animals that, for whatever reason, were simply baffling, whether it was because of their weird collection of characteristics, the lack of information on their appearance and behaviour, or the intentional obscuring of the creature’s identity (in a riddle, for instance).

But of course these categories don’t always work in Old English texts. You may be surprised how a seemingly ordinary animal can do something extraordinary, or how a critter normally associated with the devil can come to a hero’s rescue.

You categorize the snake, perhaps predictably, under “bad animals,” but you also point out that it is considered a wise animal. Other contradictions in the connotations of a single animal appear throughout the book; which do you find most fascinating, and why?

One of my favourites is the wolf (wulf), a baddie that one medieval abbot (Ælfric of Eynsham) unequivocally calls the Devil (deofol). The wulf is typically associated with savagery, anger, and deceit, but Ælfric also wrote a saint’s life in which a wulf protects the bodily remains of St Edmund. This wulf guards the saint’s severed head, making sure the holy relic is retrieved by his people for proper burial.

I also find it fascinating that wulf appears as a component in so many early medieval names: Beowulf, Wulfstan, Cynewulf, etc. Why would you name your child after an animal if you only associate it with evil? There must be layers of complexity in the wulf that transcend the labels “good” or “bad.”

The category of baffling animals is full of strange and entertaining creatures, and you carefully point out parallels to existing animals (such as the moon-head and the crocodile). How do you think these animals functioned in medieval literature and life? Did they fulfill similar roles as real-life animals?

As I said before, the baffling category is a mix. The moon-head (heafod swelce mona) is baffling because it is a bizarre-looking creature that doesn’t sound like any real animal that we know of—and its description is not even consistent across texts. I think a creature like that is meant to spark wonder in the imagination of the audience (reader or listener). You’re not supposed to know exactly what it is but be impressed by the great extent of God’s creation (because even frightening, deadly creatures were believed to be the creation of God).

A creature like the moon-head isn’t meant to teach you a specific moral lesson, and this is the case for the other baffling creatures, regardless of the way in which they are baffling. One of the riddle creatures is probably a swan (swan), though we don’t know for certain. Swans appear in medieval bestiaries, usually representing successful deception (black flesh hidden by white feathers), but this is not what the swan-like creature in the Old English riddle is meant to convey. The riddle is not a moral lesson but an intellectual exercise and a celebration of a creature’s wondrous qualities.

Linking animals with the words used to describe them, you deliver both a word-hoard and an animal treasury. Can you talk a little more about this choice, and why you think situating animals in terms of culture and language is useful and interesting?

When I wrote my first book The Wordhord, I wanted to explore early medieval society through the words people used because that’s how I became interested in history: through Old English. Many books approach history through events or people or even art, but there’s so much you can learn from the words people use. What does it mean that the same word can be used for a hero or a villain? Why isn’t there a word for “nature” (as in the natural world) in Old English? What do we make of a word that can be translated as “mind” or “spirit” or “heart” or even “inner person?”

In The Deorhord, I wanted to explore early medieval history through Old English words again but also through the lens of animal lore. Animal stories have always been more about the humans who tell them than the critters themselves, so is it any surprise that bestiaries, books of animal lore, were medieval bestsellers? In The Deorhord, I wanted to examine what people had to say about animals in Old English, even though no Old English bestiary survives. These animals, like words, tell us something about the people who wrote about them.

Your commentary on some animals points out a variety of shortcomings of Alexander the Great, who was many things but apparently not a great judge of how to interact with bizarre animals. Do you have a favorite Alexander the Great anecdote?

Alexander the Great has been the subject of histories, myths, and legends for millennia. There are amazing medieval illustrations of his alleged adventures. He explored the skies in a flying machine that consisted of a chair inside a cage held aloft by four griffins which he tempted upwards with chunks of raw meat. He explored the ocean in a glass submersible that was large enough to contain himself, a rooster (for telling time), and a cat (whose breath would supposedly purify the air). Do a Google image search and be entertained!

There is no shortage of Old English Alexander fan-fic, but I have to say the stories don’t make him come across as particularly “great,” even when he (allegedly) tells about his adventures in the first person. He never seems to learn from his experiences. For instance, he and his army are set upon by a “countless number” of snakes (wyrmas) and fight them for two hours “with no little fear.” It turns out the wyrmas were only trying to get to their watering hole, and as soon as they are able to get a drink, they leave the soldiers alone. Later that same night, Alexander’s camp is overrun by giant, multi-headed, fire-breathing wyrmas. Again, Alexander has his warriors fight the creatures, when they simply wanted to access the watering hole. Fifty people are killed in this battle. By his own account, Alexander seems a reckless and unwise leader, indeed.

Were there any animals, real or otherwise, that didn’t make the cut for inclusion in the book, but which you’d like to talk about now?

I did want to talk about bats, but there wasn’t enough material in Old English (and what there was, I’d already written about in The Wordhord). There are some truly delightful words for “bat” in Old English: hreaðe-mus (“adorned mouse,” a mouse adorned with wings) and hrere-mus (“shaking mouse,” presumably referring to its movement). Alexander the Great says in his Letter to Aristotle that he was attacked by hreaðe-mys (bats) as big as doves that had “teeth like those of men”—a terrifying image. But other than that brief mention, a few glossary entries, and a leechbook remedy that requires bat’s blood, these winged mice don’t make much of an appearance in Old English.

Jeana Jorgensen