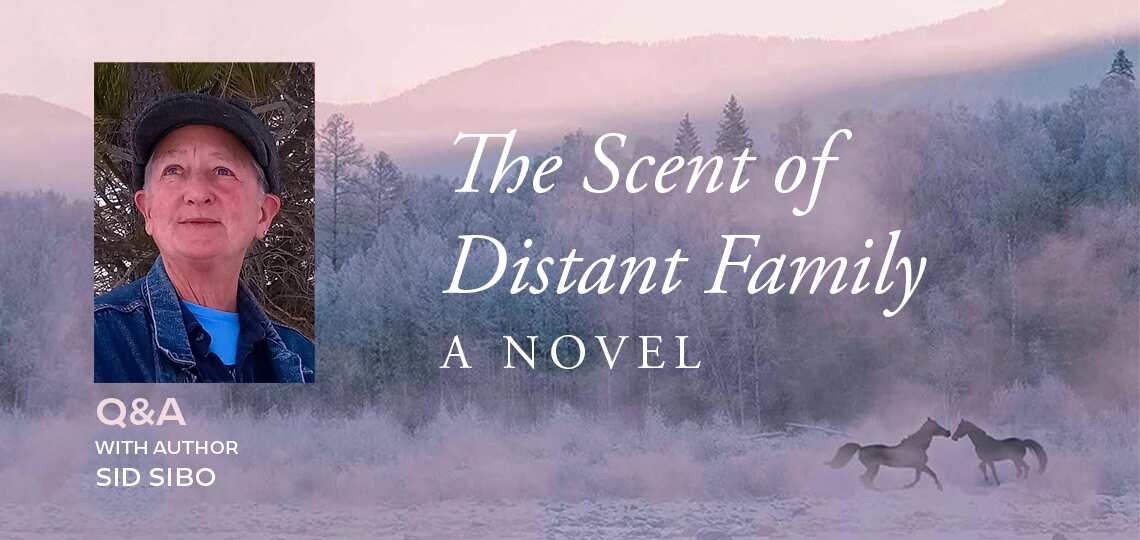

Revisioning Western Rural: An interview with sid sibo, author of The Scent of Distant Family

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews sid sibo, Author of The Scent of Distant Family

Pockets of the northwestern United States have long experienced infiltrations of wealthy city folk seeking solitude, unpressured trout rivers, mountain resorts, and wild lands with big game. And while much has been made of the clash of cultures between locals and those newcomers in the fashionable towns of Jackson, Sun Valley, and Whitefish, the great majority of the rural West is a blend of gritty, eclectic personalities making their way in harsh environments.

Today’s guest author, sid sibo, a former wilderness ranger and backcountry guide living in western Wyoming, chose to stage her debut Western novel away from the trendy mountain towns even as her characters feel the influence of venture capital and tourism. In The Scent of Distant Family, she gives voice to seven characters—a wild horse and escaped dog included—and proves to be a writer who has lived the many tradeoffs and among the many rhythms—both human and more-than-human—of the rural West.

Enchanted with sid’s storytelling skills and wordcraft, Foreword’s Matt Sutherland reached out to her for the following conversation.

In The Scent of Distant Family you pull the lid back on modern Wyoming, with themes of hardscrabbled living and new money, subsistence ranching and fracking, hyper development and environmental stewardship, and then the struggles of fragile people just trying to keep it together in marriage, friendship, and career—shot through with the story of a lost dog. Please talk about the genesis of this story and why it appealed to you as a project?

In rural areas, splitting into political camps like our country seems so intent on doing isn’t practical, even though that might be small insulation. What I found as a volunteer with my animal shelter was that people across political divides love animals—so a story that could draw in people of all stripes through a common connection with the animals in our lives held strong attraction for me. My instinct was to write a story as invitation for conversation, open to hearing different experiences in people’s lives.

The Scent of Distant Family is a wonderfully evocative title. How did you come up with it?

Because a dog and a horse provide their perspectives in the mix, I’d centered the sense of smell more than most human-focused books will, and with my naturalist background, I found that sense a unique portal to share this landscape through. The word “distant” resonated both with human characters’ ancestral families in Ireland and Australia, and with Wyoming’s paleological bounties regarding the “dawn horse” and saber-toothed cats. Family in that sense becomes a word to consider in both space and across time, and reminds us how migration is an ever-present part of life on our planet.

Nikki’s father, Charlie, is showing early signs of dementia and all of his family members are dealing with his struggles in their own way. Meanwhile, he’s just set on living as much the same way as he always has, to the consternation of everyone. His role is crucial in the arc of the story. Can you talk about the nuances of bringing him to life?

When I started this story, a friend had been misdiagnosed with early-onset dementia, and that set off ripples of stress through family and community. As people live longer, many of us wrestle with these changes and with the ways the medical profession addresses or ignores people’s needs—so I heard lots of people’s versions of how this can play out. Charlie’s pieces may have been the ones needing least revision; he seemed very alive in my imagination.

Jaye is managing her ranch in innovative ways, hoping to attract visitors seeking a new take on the dude ranch experience. But funding her venture is a challenge, so when Nikki’s brother, Phelan, approaches her with a promising potential investor, her hopes are high. This side of Wyoming—venture capital meets living on the edge—appears to be a common dynamic in recent years and you used it to great effect. What makes it interesting to you as a writer, factoring in the role Phelan plays in the book.

For me, it is a stretch to explore ways that people with money might try to act in beneficial ways in a community. It is almost a truism that people get rich by acting in ways that benefit their own bank accounts, so providing glimpses of people using wealth for good keeps me away from flat antagonists. Far more interesting to recognize our own culpability in our dilemmas than to recognize an enemy “out there.” Like Phelan potentially finds new direction during the timeframe of this story, readers also find some surprises in their understanding of Phelan.

You use seven characters as narrators, from a wild grulla mare to forgetful Charlie to his grandson Finn to leopard Catahoula Zolo, as well as Nikki, Jaye, and Phelan. That’s a lot of headspace to inhabit. As a writing discipline, what was it like to move so frequently between all of those different perspectives?

Challenge is good, right? Although my first version utilized five characters, the editor suggested “giving voice” to two more. By that time, I’d already drafted a second Wyoming story where Finn’s perspective was prominent, so that one had already developed in my imagination. Phelan’s was the final character I needed to layer into the various braids. For me, stories must always be community experiences, because the isolated individual feels just immensely false, even if that might seem easier to write.

Near the end, as Nikki—a wildlife biologist who’s lost her nerve a bit—begins to realize her family dynamic is changing in irreversible ways, Jaye steps in and says: “Around here, we’re used to figuring out who our real family is. You’ve got one in there, if you want it,” referring to a handful of bighearted locals waiting to embrace her after a successful search and rescue. In the main, notions of family and relationship drive the book from beginning to end. And you leave readers with ideas about how Nikki and Jaye might become closer, perhaps even intimate, friends. How did your definition of family become so expansive?

When I was growing up, and for my parents’ generation too, kids found caregiving adults and de facto siblings all over the place, not just within the walls of a nuclear family home. Family that wants good things for you, and that pushes your assumptions—why would we circumscribe those relationships, or limit them even to humans? Some of the most popular videos in feeds all over the internet include surprising connections across different species. Expansive, yes! That’s the word we want when we think about family, isn’t it?

There’s so much about the book we haven’t discussed. What do you hope readers take away from The Scent of Distant Family?

One question that I hope lingers for at least some readers is one Nik wrestles with, as a scientist, of needing to know the (right) answer. Given the realization of so much about the universe we don’t know, might we be more hopeful if we don’t cling so tightly to what we “know” based on our limited knowledge? Might we be less frightened and more willingly collaborative?

What’s next for you as a talented storyteller and writer? Are you working on another book?

The drawing board right now is full of characters in far northern Minnesota, where I lived right after college. Those years and that landscape (with its characters) formed many of the curiosities I’ve chased ever since, so I’m excited about being there imaginatively alongside some of the new thinking and conundrums of our contemporary lives. And yes, that second Wyoming story with returning characters from this one is waiting in line.

Matt Sutherland