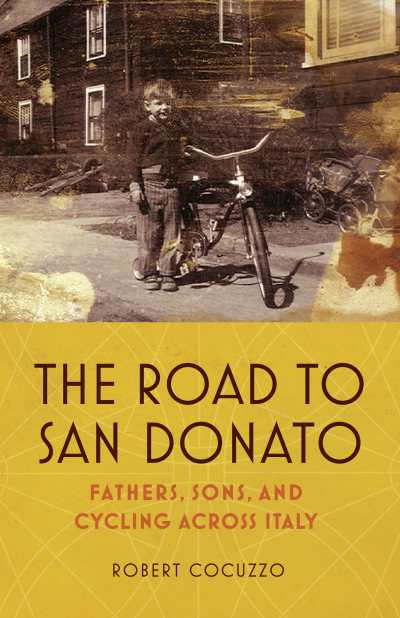

Reviewer Wendy Hinman Interviews Robert Cocuzzo, Author of The Road to San Donato: Fathers, Sons, and Cycling Across Italy

Savvy travelers get that way through experience. Nobody’s born with artful packing skills or an innate sense of how to lessen the effects of jet lag. That’s a lesson we learned the hard way after many years of attending three or four international book events a year. But along the way, we also picked up a few tips to ease the inevitable strains of travel, including one we’ve found to be especially helpful for sleeping well at night on the road and overcoming the bloat and discomfort of wining and dining to excess day after day.

Get outside and push yourself physically. Yes, pull on those running shoes for a brisk morning run or take a long, strenuous afternoon walk—you’ll be glad you did.

Within reason, we might add. We don’t necessarily recommend you take a 425-mile bike ride through the quite steep hills of Tuscany. Yes, we’re looking at you, Robert Cocuzzo. The author of The Road to San Donato, Cocuzzo tagged his aging father as a companion on the two-week journey, so the book subplots include the father-son dynamic, as well as Cocuzzo’s interest in Jewish history and how the Holocaust left its mark on the Italian peninsula.

The other half of this week’s FaceOff is reviewer Wendy Hinman, herself an accomplished long-distance traveler, albeit on the high seas in a small sailboat. Hinman reviewed The Road to San Donato in the September/October issue of Foreword Reviews and with the help of Mountaineers Books we made the reviewer-author connection.

Wendy, take it from here.

While your book is a travel memoir of cycling through hill-country in Italy, it is also about many other things: the refugee/immigrant experience; the parent-child relationship, responsibility, and the meaning of love; the ravages and uncertainties of war and the meaning of sacrifice and guilt; and dealing with our own personal gremlins. It’s a pilgrimage and a journey of self-discovery but also one of forging a deeper bond with the people who know us best yet challenge us the most—family. What did you find most difficult about your journey? Was it the logical challenges, the bikes breaking down or your bodies protesting such a punishing schedule or was it the dynamics of your relationship with your father and your ailing grandfather or what you might discover in San Donato that worried you most?

With any adventure, you’re going to be tested. On a subconscious level, that’s really why you go: to put yourself in a situation that shakes you out of your normal routine and allows you to discover new depths within yourself. The 425-mile cycling trip I embarked on with my father certainly posed a whole host of physical and logistical challenges, but the real tests were far more mental and emotional.

Before we left the States, I anxiously pondered how my relationship with my father would fare when thrust into a set of extreme circumstances. Would we flourish or flounder? Would we return home with a new level of communication or would we never speak to one another again? Navigating our relationship, both while pedaling the bike and then writing the book, proved to be the greatest adventure of them all.

Through travel, we often learn about ourselves as we face challenges along the way. Situations force us to draw upon inner resources we didn’t know we had and face our fears. In my seven-year sailing voyage, I pushed myself beyond what I thought I could do and discovered a bolder person than I had known before. What surprised you most about this journey and how it affected you personally? In what ways did this trip catch you unprepared?

Whether it’s blind optimism or willful ignorance, I have a habit of simply assuming things are all going to work out. When we set off on this wild adventure, there were so many questions surrounding our preparedness that I was willing to simply let go unanswered. Were we physically capable of cycling the distance we had planned? Would we be able to figure out how to navigate hundreds of miles from Florence to a tiny little pinprick on the map? Would we even be able to find rental bikes that would be suitable for this kind of long-distance ride? Suffice it to say, there were a lot blind spots that could have caused us to crash.

Ultimately, it was my own physical deterioration that surprised me most. My body began failing to the point where I thought I’d just have to stop. In those moments, when I was in the deepest, darkest reaches of my pain cave, I thought about the book Touching the Void, the true story of a climber who falls into a crevasse and decides that his only way towards survival is to climb deeper into the abyss. So it was for me. Through suffering I became stronger. The key was that I had to keep moving.

It’s easy to fall into old patterns of interacting under normal circumstances, but when we spend significant time with others in a new scenario as happens in travel, you can learn things about one another you hadn’t known before. The dynamic of your relationship with your father has changed significantly since you lived under the same roof. How has this bicycling adventure helped you see your father in a new way?

The cycling trip gave us an opportunity to really talk for once. We had two weeks to ask one another all the questions we had previously just assumed we knew the answers to. Through that process, which could have taken place playing checkers as much as pedaling bikes, I began to understand my father’s motivations, fears, processes, and impulses with a whole new level of clarity. And with that new appreciation, I was also able to better understand all those traits that I had inherited from him. And that’s really the point of this book: to inspire readers to pause, to look around at the relationships closest to them, and take the time, real quality time, to get to know that person in the deepest, most intimate ways possible.

Your story muses on the fleeting nature of time and the natural role reversal that occurs between parent and child in the course of aging—with your own father as you tackled the hills of Tuscany and with your powerful but ailing grandfather who had long dreamed of doing this pilgrimage to the old country. As a daughter of a sailing family with a father now reaching eighty, I could relate to the role reversal that occurs when, on a recent sailing trip, I saw my father’s pride prevent him from accepting his new physical limits and also his inclination to doubt my sailing skills, though I’ve sailed 34,000 miles—far more than he’s ever dreamed. It’s a delicate balance to take the lead while preserving the dignity of one who first taught you and not get irritable. How did you manage this while still sharing your common love of sport and reaching this goal with your dad? How has your relationship changed with both your father and grandfather?

My father blazed his own trail in every single aspect of his life. So, too, on the bike; he was never one to follow the lead of another person—especially not me. The role reversal took place gradually, with us needing to hit a crux that would force him to take his hand off the tiller and trust me. Once he did that, my father seemed to really open up to the many gifts that this adventure delivered for us.

One of the joys of travel is the characters we meet along the way and the surprise discoveries. In addition to lush Italian scenery, your story is filled with vivid characters that defy stereotypes: the opera-singing bicyclist, the nontraditional Italian woman and her same-sex lover, the cycling star turned unsung war hero. These people are charming. Not only do they enrich your journey, they also provide an example of courage despite the risks and making sacrifices for the good of others. Your story offers a glimpse of modest heroes in a tale about what it means to be a role model. Who most inspired you of the people you featured in your story?

I was most inspired by the heroes who saved the lives of Jews during the Nazi occupation of Italy. Many of them were common village folk with everything to lose and nothing to gain from helping these poor people. And yet they seemed to do it out of instinct and an unshakeable belief in what was right and wrong. I had the great privilege of meeting one of these heroes during my adventure. That hour I spent in her presence felt akin to what I imagine it feels like meeting the pope, the Dalai Lama, or some other saintly figure living on earth.

The war and cycling history that threads through the entire story and your discoveries in San Donato deepen this travel adventure significantly. How did you uncover these lesser-known details and how did it enhance your travel adventure?

As with all great discoveries, I learned about this history through my own intense curiosity, which made me open to learn more and more along the way. We were fortunate to meet a number of compelling storytellers during our time in Italy. Each conversation gave me more thread to pull on. Unraveling that history brought a whole new layer to not only our cycling trip and time in Italy, but also to my life in general. In coming to understand that past, I became armed with new tools for navigating my future.

Wendy Hinman