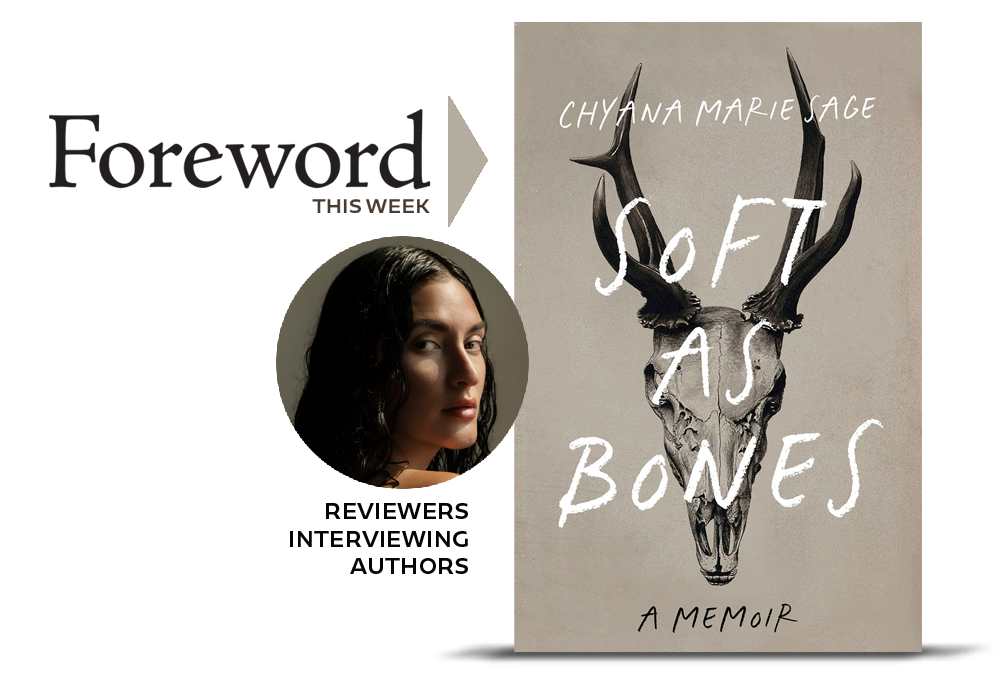

Reviewer Suzanne Kamata Interviews Chyana Marie Sage, Author of Soft as Bones

“In my culture, circles are very important, as well as the spiral. It represents connectedness, and I was always taught that we are connected to everything around us, and everything that came before us, and everything that will follow.’’ —Chyana Marie Sage

Today’s guest Chyana Marie Sage identifies as Cree, Métis, and Salish, indicating her indigenous, Western Canadian ancestry—and so much more.

With some understanding of the Cree and Salish people, let’s turn our attention to the Métis, a French word meaning mixed, which points to relations between French fur traders and Indigenous women beginning nearly five hundred years ago in a much wilder North America. Now formally recognized as a First Nations people by Canada, in the mid 1800s, the Métis first advocated for territorial rights and then defiantly declared a provisional government at the Upper Fort Garry fort in 1870 that eventually led to the province of Manitoba. Ongoing negotiations between the Canadian government and Métis led to a series of signed treaties that were repeatedly broken by Canada between 1871 and 1907.

According to the 2021 census, nearly 625,000 people make up the Métis Nation in Canada. Their language is called Michif, one of 170 or so Indigenous languages currently spoken in North America, from more than 300 that existed before European colonization.

Chyana’s Soft as Bones earned a starred review from Suzanne Kamata in Foreword’s May/June 2025 issue. Four more spectacular memoirs were recently honored in our 2024 INDIES Book of the Year awards and deserve your attention—The Mourner’s Bestiary (gold); The Braille Encyclopedia (silver); Warsaw Testament (bronze); and Loose of Earth (honorable mention).

Make off with your free digital subscription to Foreword, here.

Soft as Bones is written in a collage of different styles, interweaving Cree legends and word definitions, personal experience, poetry, letters, interviews, and so on. How did you come up with the structure? Was it there from the beginning?

I knew from the very beginning that my structure was going to be very different from things I had read before. For this story, I knew that a linear format wouldn’t do it the justice or tell the stories I needed to tell in the best way. I needed it to be as authentic as possible, not just to my own story and journey, but also the stories of my family members and ancestors. In my culture, circles are very important, as well as the spiral. It represents connectedness, and I was always taught that we are connected to everything around us, and everything that came before us, and everything that will follow.

The first thing I focussed on was just writing the memories and stories out, all in different documents to begin with. When I got close to the end in terms of everything I needed to include in the story, suddenly it was like a lightbulb turned on. I kept thinking about the structure before then, but it still seemed out of reach for me. I was in my thesis workshop and my professor was saying something profound about memory that I have since forgotten, but immediately it dawned on me, and I stopped listening to what was being said. I had a blank piece of paper in front of me and I drew a small circle in the center and that was my core childhood trauma. I then started drawing more circles around it, creating a sort of spiral, and each line represented a different family member, and then I had these arrows coming in and out of the center, representing different folktales and ceremonies.

It might sound sort of insane when I try to describe it, but that was the moment it clicked, and I knew exactly how to weave it all together. It was a braided spiral, braiding and winding all of the different threads together to make up our cohesive whole—it was the only way to show that philosophy of connectedness, like we are the cycles, we are history and present all at once. I still have that piece of paper.

Memoir requires a degree of bravery. Did you ever consider writing your story as fiction? How did you conjure the courage to write it as truth?

I never considered writing our story as fiction … for me, to do that, felt like it would be an injustice, like it wouldn’t be honouring what happened to us and how we moved through it. So much of our story was and is about uncovering truth and working through lies, so to write my truth as fiction, would feel like a lie.

When I read fiction about some of the darker things that happened in our very real, lived lives, it feels like sensationalism. What happened was true and it should be seen as truth. These are not fictions or made up stories in a book, these are the very real lived experiences of Indigenous people across Turtle Island and they need to be told. My story is what can happen and what does happen from the legacy of colonial harm, especially in regards to Sixties Scoops and Residential Schools. Thinking beyond that, I also think profound growth and healing occurs when we confront the greatest forces of darkness in our lives, whether internal or external forces. Me writing our story and telling it felt like the last step I really needed to take to work it out of my nervous system before I could move on to this next phase and chapter in my life.

I imagine that writing this book was cathartic, but also potentially traumatic. What kind of selfcare (or other care) did you rely on in the writing of Soft as Bones?

It was the most cathartic experience of my life. It was like my own personal quest of understanding, but even still, of course there were moments that were hard or I would find my body physically not wanting to write certain things, particularly around my sister, Orleane. I felt and do feel very protective of her. When some of those hard moments came up, I relied on my coping techniques I had thankfully had a decade of cultivating. For me, it was long walks in the park. I would just put in my headphones and walk to the river and sit upon the rocks for a while and just watch the current.

Another thing was talking with my loved ones. I would talk on the phone with my mom multiple times a week, because I was living in New York at the time, and we would talk for hours. Sometimes we would cry together, but I leaned on her and my best friends. We have to release things, so talking about things has always helped me do that. Talking and walking, it’s simple, but for me it was very effective.

How do you feel about trigger warnings? Is it best to confront our demons, or avoid them?

I think trigger warnings are very useful, because you never know where another person is at in their journeys and how hard something you are speaking or talking about might be impacting them, so if they have the knowledge of what is coming, the agency is left with them to decide if they have the capacity to be in that space or not. That being said, for me, I believe in facing my demons head on. That doesn’t mean it was always that way because there was a time when I was running, and I think we all have that, but at some point you stop and look around and think, where am I? And where am I going?

For me, I realized I needed to go back to everything I was running from in order to figure out where I was meant to go next. I confronted those darknesses. I confronted my father. I confronted everything I had buried away, and in doing so, I set myself free. Because if you are running, you’re in a trauma response, and I didn’t want to let what I went through dictate how I was able to move through life anymore.

In the US, and also, I believe, in Canada, there has been some backlash against DEI initiatives, ie, funding cuts for organizations and events that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. Are you concerned about this? What do you think is the best way for authors and other creatives to respond?

I think it is our duty as authors and creatives to fight back against it. It was Louis Riel that said it would be the artists who gave us our spirit back, and I think now more than ever we need to use our voices and platforms as a way to fight back against these harmful cuts and ways of thinking. Certain people like to glorify the past, but when I look back, especially around colonialism, the harm that was committed was so severe that the ripples are still being felt—that’s exactly what Soft as Bones is all about. We have to be forward thinking when it comes to a lot of things—climate change, rectifying the harms committed in the past, fighting against homelessness, and lowering recidivism rates. It can be exhausting for us BIPOC to constantly be fighting these battles, but I can say it is a battle I will never stop fighting.

However, even amidst these cuts and backlash against DEI initiatives, there is a TON of excellent work being done by community members. We have the choice for what we tune into when it comes to social media, and when I log on to my social channels, I see incredible work being done in our communities. I think of Shayla Stonechild with Matriarch Movement. I think of Kinsale Drake with the NDN Girls Book Club. I think of Notorious Cree with his dancing. I think of Arsaniq Deer with her traditional Inuk tattooing. And that’s just to name a few, but the good work is still being done no matter who tries to silence it. I know us creatives will continue to work in that space.

How has your community responded to your book? [This interview took place in late April.]

So far leading up to it, I feel very taken care of. Starting with my own family, they have been supportive every step of the way while writing it, and being open with their stories and wanting me to include that in the book to really capture the full essence of our story. NDN Girls Book Club is another organization that makes me feel so taken care of. They have been championing the book on social media and we have partnered together for my book launch/fundraising event in Toronto on May 5th. It will be their debut in Canada, so we will have free books to hand out, and Shayla Stonechild is going to DJ the event for us. So even just starting from the jump, community feels very involved and present and I can’t wait to just keep expanding that, hoping that my words will help a lot of people heal.

Could you tell us a bit about your work with Connected North, fostering self-love and healing in Indigenous youth?

Connected North is an amazing organization that brings different/unique curriculum to remote Indigenous communities across Canada. I was the student inspirational speaker at Indspire’s A Feast In The Forest 2024 and the people who work for them approached me after my speech to offer me a job with them. I teach a couple different courses with them, one is about fostering self-love through writing, doing writing exercises, and sharing different tools for how to do so. Another one is all about Braiding Essays, and then one where I get the student to write their own Wesakechahk stories. It has been such a beautiful experience and I love hearing the stories and words that the Youth come up with. It brings me so much fulfillment to be able to share the things that have really helped me throughout the years and give back.

What’s next?

Right now, I am working on a magical realism novel. But, I also wrote a TV pilot and a short film. I really love screenwriting and want to invest more in that in the future. The goal is to eventually make Soft as Bones the movie. But I am preparing for a move back in Canada, because I can feel my people calling and really want to be in community again. I don’t know if it’s goodbye forever New York, but it’s time I come back and ride for my people after everything I have learned. The goal is to work for a really solid Indigenous organization now and keep up the good work.

Suzanne Kamata