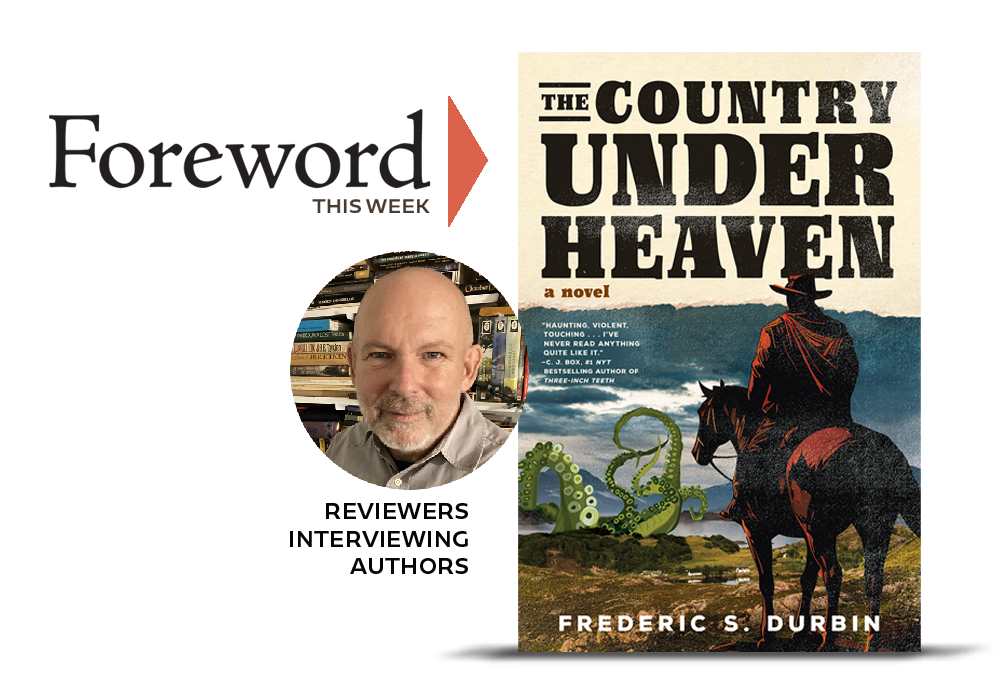

Reviewer Ryan Prado Interviews Frederic Durbin, Author of The Country Under Heaven

A few weeks ago in an interview discussing her book Enchanted Creatures, Natalie Lawrence explained that our fear of monsters is deeply cathartic because it allows us to glamorize fear, engage with it safely, and enjoy “all the thrills with none of the danger.” It was an aha moment for us. Suddenly, we understood why people search out books and movies that scare the bejesus out of them.

And in this week’s interview, Frederic Durbin adds another tangent to this idea by suggesting that the reason we read and write fantasy and horror stories in the first place is because they depict life closest to what it really is. “The fact is, we live in a world of horrors. I would even say it’s a world of supernatural horrors as well as mundane ones. Those horrors can take all sorts of forms—injustice, abuse, disease, mental illness, addiction, prejudice, corruption, cruelty, accidents, unfaithfulness, mortality … our human problems haven’t essentially changed in the history of our species. Monster stories give these horrors shapes; they help us externalize our horrors into something we can fight against or escape from. That’s why we’re still telling monster stories.”

Which leads us to the demon that stalks Ovid, the protagonist of Frederic’s supernatural novel The Country Under Heaven. Ovid barely survived the Civil War’s Battle of Antietam and, with a nod to PTSD, Frederic admits that this haunting creature is “symbolic of the darkness that follows any who have seen the horror of what humans can do to other humans.”

In his starred review, Ryan Prado called the book “a cosmic Western novel that doubles as a psychological treatise on the hidden wonders of radiant and mysterious inner worlds.” With praise like that, we knew reviewer and author would have plenty to talk about.

Many, many more reviews of wonderful new novels appeared alongside The Country Under Heaven in Foreword’s May/June issue. Digital subscriptions to Foreword are free.

The Country Under Heaven is such a visual novel. I wonder how much of the travels that Ovid experiences in the book were echoes from travels you’ve done yourself, or at the least that the way in which Ovid observes the world around him mirrors your own approach to travel and to ensuring the taking of stock in what’s around you is paramount.

Ironically, I haven’t traveled much in the American West! But I think you hit it square-on in mentioning observation. I grew up in rural central Illinois, and I think if you grow up in rural anywhere, and if you pay attention, you can bring a certain quality to almost any kind of fiction writing. Writing about the American Old West comes pretty naturally for me, because it feels like it lies in a past that’s mine, in a land that’s mine, in the broader sense. By that I mean that I’ve also done a lot of fiction work set in an alternate Victorian England, and that land isn’t mine. That was a lot harder to do. But the American West lies in my past, my fairly recent past. Compared with other countries, our country has a pretty short history. The trees I grew up seeing were the same kinds of trees that were there in the 1800s. They look the same. Foxes now were foxes then. Sunsets look the same.

I am fascinated with natural landscapes, with flora and fauna. If I pass near an interesting tree, I’ll stop and study it, gaze up into it, and admire it. The books I love the most direct attention to the growing things in nature. Watership Down, by Richard Adams, begins and ends with primroses. J. R. R. Tolkien, amidst the fantastic vistas of Middle-earth, always shows us the trees, the mountains, the flowers in great detail. He believed that if you really see and appreciate a leaf in our own world’s forests, you can write about a leaf in elfland. Fictional worlds always become much easier for me to believe in if I can see their plants, their geography, their trees.

I figured out that Ovid is like me but more so: he knows the names of all the flowers, trees, and other plants. For the love of it, he studies books that classify and describe them, and he connects that learning to what he sees. He finds great joy in knowing the creation, this sprawling garden that we live in. In pretty much every chapter of the book, he’s in a different state, a different part of the country, and I needed to know what that region’s trees were, what wildflowers grew there and were in bloom in the season I was describing. What thrived in full sunlight? What preferred light shade or deeper shade? What animals were there? What did they look and sound like? What were their habits? For all of it, I wanted pictures. Thank Heaven for the Internet!

In one chapter, Ovid is describing Montana, and he says it’s as if, when he made that country, God didn’t put the roof back on, so it’s like looking straight up into Heaven. And he’s talking about the Appaloosas, and he says it’s like all the horses were standing around outside a shed that was full of white paint, and dynamite went off inside the shed. I’ve only seen pictures of Montana and Appaloosas.

Without giving too much away from the book’s plot, let it suffice to say that there appears a thin boundary between worlds in your book. Was there a certain experience or series of experiences that helped to guide that surreal aspect to Ovid’s visions, or his ability to be affected by them and to utilize them in practical ways?

I grew up reading and loving fairy tales and other fantasy stories, and they often involve passage into other worlds … magical places that are a little different from our own. There is an old belief underlying many of our stories and holiday traditions that, at certain times, the boundaries between worlds grow especially thin. There are times of year and times of day and night when—according to stories—it becomes much easier to go from one world to another.

The games my friends and I played as kids often included journeys into some Other Place—down through the volcano to reach the center of the Earth … down into the ocean depths in our submarines … far out into the cosmos in our spaceships … I loved stories about the voyages of Sinbad—mysterious islands, lost fabled kingdoms and the like … abandoned, overgrown cities of opulence and ancient secrets. I loved King Kong, its mysterious island with its gigantic wall, a huge gate in the wall. I always wanted to know “What’s behind the wall? What’s through the door? What’s down this secret staircase?” My previous novel, A Green and Ancient Light, is all about the border between two realms, our own and the land of Faery.

In Ovid’s book, the chapter “The Sound of Bells” is really close to fairy tale, and it’s also based heavily on something that was recorded historically as an incident that actually happened.

As for practical applicability, I think the things we learn from the old stories help us do a better job of living in our world. Our real lives are full of doorways—new steps to be taken, thresholds to cross, decisions that require courage. We have to get through some dark tunnels. When we have to face these things, it helps to be able to remember the people in the old stories and how they did it, the virtues they took with them, the reasons they went onward, what they held onto.

How did you settle on the era of this story, the late 19th century, in the wake of the Civil War, to set the scene for Ovid’s explorations? In what ways do you think setting the book in this epoch over another allowed it to burst from the page the way it does?

Well, most of all, it’s an era that fascinates me. We often hear the advice to “write what you know.” If people did that, we wouldn’t have any new books set long ago or in the distant future. Much more important, I think, is to write what you want to know; write what you love, what you’re obsessed with.

Since I was a kid, I’ve loved stories of the American Old West. I’m sure I picked up that “bug” from my dad, who owned horses and read westerns and told me stories about famous figures of the West, of life on the trail, of the ways people did things. He was basically a cowboy who was born too late and too far east. As a young man, he wrote poems about moons over canyons, coyotes howling, life in the saddle …

But beyond all those trappings and tropes, there’s a poignance, a pathos to the Old West. It was a relatively brief period, and it was all about change. Native Americans were being forced off the lands they’d known for generations. Rails were being laid, telegraph lines strung, the buffalo being slaughtered. White people were flocking westward after minerals, occupying the land, putting up fences in a country where fences had never been a thing. It was a harsh life out there. There weren’t many old people, and almost no one had a Hollywood smile. Stories of the West are mostly elegies—sad, beautiful songs about loss, about endings. Ways of life were vanishing. We were losing things that would not come again … and it was all happening in the most dramatic and beautiful setting—a lovely land that could kill you in the blink of an eye. In places of very little law, personal actions make a tremendous difference. Evil gets really ugly fast. Integrity and kindness are more precious than ever. So these big, epic, stirring human stories practically tell themselves.

And of course such stories have never been more timely. Like Ovid’s land in the wake of the Civil War, our present country teeters on the brink of another one. There’s anger, deep resentment, hatred for the Other. There’s an excellent book, Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War, by Harry S. Stout, that explores how both sides in the Civil War believed they were morally right, that they were on God’s side. Doesn’t that sound chillingly familiar?

Ovid’s manner of speaking is intoxicating—that thoughtful, beautiful, aware, and gritty introspection catapults his character into the realm of the unforgettable, in my opinion. What, if any, methods or research did you employ to nail his cowboy poet turns of phrase and perspective on the things happening around him?

First of all, I should say that this novel was a new threshold for me, a new kind of storytelling in that the character’s voice was the very first thing that came to me. In everything I’d written before, it was place, the setting, that spoke to me first. Some place would intrigue me, and little by little, I’d figure out what story was happening there and whose story it was. For the first time, a character just came to me and started speaking, telling me his story. It happened again with the sequel to this book, which is about a different main character.

Yes, it is a pretty compelling voice. And I’m not taking credit for that. That’s Ovid’s voice. I don’t feel like I “created” it in any way. P. L. Travers wrote a short essay about how Mary Poppins found her, and I know what she meant. Ovid found me. He needed someone to write down his story, and he took a chance on me.

If I had any part in shaping Ovid’s diction, it’s partly how the people in my home county talk, especially the older farmers. I also read a pioneer diary, Days on the Road: Crossing the Plains in 1865, by Sarah Raymond Herndon. I took notes on the way the author expressed things. There’s nothing like a firsthand source, something written by a person in the times you’re trying to evoke. My dad’s side of the family came up from Tennessee, and the voices of my older relatives were in my ears, their speech patterns and expressions. People in the nineteenth century, if they got some education, read sources that were pretty classical, so there would often be a combination of lofty language and rural vernacular. It’s a lot of fun to try to recreate. I think a fairly recent example that does it quite well is the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit. It’s a joy just listening to how the characters in that film talk—which credit really goes, I suppose, to Charles Portis, who wrote the novel. The movie is very faithful to it.

Did you expect or do you believe that Ovid came to be a hero in this story? In what ways do you believe he achieved that title, if so?

He’s more like real-life heroes, I guess. He’s not a John Wayne character, not a Superman or Beowulf. Ovid is just a steady, wise, quiet-talking guy who shows up; he’s consistently there and helpful. When people ask him for help, he gives it. Instead of a typical western gunslinger, he’s more like an itinerant pastor, traveling around bringing peace, bringing his equanimity, bringing hope. He helps to put things and people back together in a land that has been shattered by war. The real differences he makes aren’t with his gun, though he uses it when he has to. He makes his differences with kindness, compassion, patience, and wise counseling. From Ovid’s Christian worldview, he sees people as having been built with a good design, made in the image of God, but now broken and messed up, in need of healing. He operates in the glow of a light shining in from beyond this world, and he helps others move closer to that light. It’s why the book is called The Country Under Heaven: we’re certainly not in Heaven yet, but we’re on its doorstep. We’re right underneath it. The grand human struggle, since we left the Garden of Eden, is trying to get back home. God makes it possible, and Ovid is kind of like a train conductor on that homeward journey.

So, yes, I believe he’s a hero. Did I expect it? Well, he had a big story to tell. When he started talking, my reaction was something like, “Well, Sir, I see by your outfit that you are a hero”—that sort of thing.

There is always tension just below the surface of the book, fueled by the seeming omnipresence of the main—though nebulous—antagonist being that looms just out of reach of Ovid during his sojourns. With the backdrop of post-war traumas also firmly implanted throughout the text, to what extent was the idea of mental health also a kind of shadow lurking in the corners of The Country Under Heaven?

It’s definitely not something I set out to do. I didn’t sit down and say, “I’m going to write a novel about PTSD.” But I think if you faithfully tell a story about characters who have gone through a trauma such as war, then the toll it takes on them, the injuries it leaves them with, are going to be part of the story. Ovid is damaged by his wartime experiences, and he interacts with others who are damaged, lost, and hurting for various reasons. He himself isn’t sure what his mind is doing. He wonders what’s in his mind and what’s outside it. I suppose the nebulous, ominous Creature—or “Craither,” as Ovid calls it—is, on one level, symbolic of the darkness that follows any who have seen the horror of what humans can do to other humans. It’s an unpredictable darkness that, for some, can erupt in devastating moments.

In what ways do you feel that the specter of Lovecraftian undertones, as found in your book—ancient creatures living amongst us, or very near, when the light shines just right—continue to serve as gripping bedrock for a story? How does a writer embrace those narratives while also bucking the trends of their longstanding incorporation into storytelling?

I heard the writer Peter Straub say something to the effect of, “We read and write fantasy because it’s the genre most capable of showing us life as it really is.” Probably others have also said more or less the same thing, and I think there’s a lot of truth to it. Straub has written a lot of horror, and we could add horror to his list. The fact is, we live in a world of horrors. I would even say it’s a world of supernatural horrors as well as mundane ones. Those horrors can take all sorts of forms—injustice, abuse, disease, mental illness, addiction, prejudice, corruption, cruelty, accidents, unfaithfulness, mortality … our human problems haven’t essentially changed in the history of our species. Monster stories give these horrors shapes; they help us externalize our horrors into something we can fight against or escape from. That’s why we’re still telling monster stories. The oldest tale we have that was first written in some form of English is Beowulf. The manuscript was written sometime between 975–1025 CE, and it may have been an oral epic for a long time before that. So it’s our oldest native English story, and it’s a monster story.

As storytellers, how do we avoid rehashing? How do we make these specters and creatures feel original? Well, we can put them in unexpected places, like the Old West. We can write about them vividly and well. People often don’t realize the value of good writing, but think about it: we’ve known for most of our lives that whales exist, right? We’ve read whale stories, and we wonder, “What could be new and interesting about a whale story?” But say that a whale blasts up out of the ocean fifty feet straight in front of you. You’re drenched with the spray. This tower of gray blocks the sun, and in that umbrage, you know the chill of mortality, of all that you can’t control in the world. The whale is a leviathan, impossibly long, colossal in girth, its hide crusted with barnacles. You look it in the eye, and the eye is looking back, right at you. The gargantuan shape hangs there above you, suspended in a frozen moment of uncertainty, a wonder you’ve never seen and probably won’t see again, and then it comes thundering, crashing down, and you hear its impact on the water like the Earth has been split to the core, and you hang on for dear life, and the boat you’re on is like a toy flung up by the sea, and you pray it will come down rightside-up, and that there will be something of it left to get you back to dry land. You can’t possibly think that whales are a tired concept ever again, because you’ve seen and felt one up close. Whether you’re writing about a dandelion seed or ice cream or heartbreak or the end of the world, that’s what good writing does. It allows you to see and feel things up close.

And finally, as writers, we need to remember that we’re always telling human stories, even if our characters aren’t human. If readers are engaged with characters going through things, they won’t care if they’ve run into your monsters before.

Ryan Prado