Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Leah Altman, Author of Cekpa: A Memoir in Beaded Essays

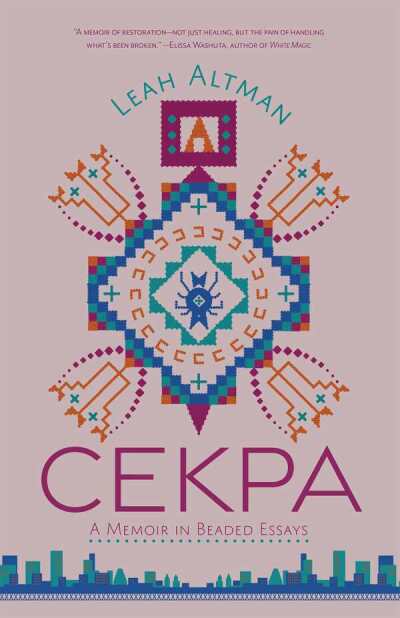

At this precarious moment in our planet’s life-as-we-know-it, ironic to think that the Indigenous peoples our European ancestors booted off this land hold the knowledge that we’ll need to survive. To better grasp this fact, take note of the title of this week’s featured book: Cekpa—that’s what Lakota women call the beaded leather bag in which they carry their own umbilical cord.

With Mother Earth in mind, take a moment to think about why these women might want to carry that dried, shrunken piece of connecting tissue (dare we say, the mother of all connectors?). Wouldn’t we all benefit from having and holding a talisman-like reminder of our dependency on this life-giving planet?

Rebecca Foster tagged her Cekpa review with a rare star and welcomed the opportunity to submit a few questions to Leah Altman, author of an extraordinary memoir-in-essays.

How did the overarching metaphor of the cekpa influence your book’s form? Did the structure inform the contents, or vice versa?

I didn’t set out to write in a particular structure, necessarily, and that actually became kind of a challenge later on in the editing process. Cheryl Strayed was my first memoir writing instructor, and she taught me how to write by using a moment in the present to trigger a memory … so you end up going back in time via a flashback of sorts. Then, you are pulled back into the present by the end of the piece/essay.

I was in a critique class when one of the other students pointed out that my writing style is more circular than linear because of that approach of looping in time. Originally, the structure of the book was also more circular, with each chapter or essay in a non-chronological format, but combined with the looping in time within each individual essay, readers said that it was too much jumping back and forth and difficult to keep track. So with Pam Houston’s help (Pam was my mentor at the Institute of American Indian Art), we restructured the essays in a more chronological format to reduce the confusion. The student in the critique class said that the chronological ordering of the looping essays was like the thread that holds the beads together. She gifted me with the subtitle: “A memoir in beaded essays.”

You write about developing your public speaking skills. What role did finding that literal voice play in accepting your identity and becoming an author?

I have come to accept that I will always dislike public speaking. As a natural introvert and someone diagnosed with major social anxiety, I will never fully enjoy it. However, regular exposure has helped me learn how to become effective at it. Additionally, I tend to enjoy taking risks for the adrenaline and dopamine high, so it’s a healthy way for me to indulge in risk-taking behaviors. The “happy hormone” rush I get after public speaking is akin to the one I get hiking a mountain (without the physical exhaustion!).

I’ve been an executive director at a local nonprofit now for over a year, so that role has helped me prepare to do readings. I’ve also performed my poetry and done some readings of essays I’ve written, and I minored in theater for my undergrad, so I rely on those experiences.

How have rituals mediated your rediscovery of your Indigenous roots?

Ritual is a big part of Lakota spirituality, as I wrote about in the chapter “Hemblecha.” The repetition of actions, prayers, and songs is calming, meditative. For me, it’s a lot like hiking. There are many different ways I connect with nature and the land, and while I don’t subscribe to a particular religion, I do consider myself a deeply spiritual person; my spirituality really centers on that connection to the land.

At work, I meet with a lot of non-Native funders. I work for a Native-led organization that amplifies Native voices along the Columbia River, and we work at the intersection of art, education, and environment. But a lot of the funders I work with want to put our work in one box. For example, they frequently ask me if we are an art organization or an education organization or an environmental organization. They want me to pick one label for our work. What I am always trying to explain is that Native cultures don’t separate our connection with the environment from our art or anything else we do. The land is always at the center of things, it’s where everything we are comes from. When I try to think of my connection to the land as separate from who I am as a person, it feels like my head is going to pop because I just can’t think that way. My brain won’t do it.

So if that’s what it means to be an Indigenous person or to “reclaim” my culture, I guess that’s how I would describe it. It’s that relational worldview, as opposed to a Western, linear one. And I was definitely raised in a Western worldview, but I’ve been immersed in a relational worldview for so long, I don’t think I could ever go back. But I do fall back on my strengths in linear thinking when I need to … like for deadlines. Linear thinking is very helpful for deadlines.

There are a few lyrical sections that feel almost like prose poems. Do you also write poetry?

Yes. Poetry is what brought me to writing. People have pointed out to me that the way I think and talk is very artist-like, and I think that’s all the poetry talking. I was eight years old when I read Romeo & Juliet and fell in love with writing. I knew then that I wanted to be a writer and that I wanted to write a book one day.

My poetry feels really private to me because it deals with my deepest emotions, so I don’t share it often. There is also a part of me that doesn’t want to open my poetry up to critique because I like the way I write poetry and don’t really seek to change it because it’s more like therapy to me than anything else.

Your reunion with your birth family is not the stuff of rosy clichés, and you chose to publish this despite relatives’ disapproval. What was your motivation and how did you overcome the emotional obstacles to publication?

I wrote my story. Theirs is different, but everyone has a right to share their story, their truths. Writing helped me get through the toughest moments in my journey to self-discovery, and they were just a part of that journey. Writing saved my life. I fully believe I would not be here if I did not write about my experiences. I know firsthand that art saves lives, and if my book can help save one person’s life or bring someone healing, then it was worth it.

I’ve already had some early readers who told me that my book helped them feel not so alone in their struggles with mental health issues. I think about my niece, who is reading my book now, who has struggled a lot with her own stuff, and the classes of teenagers I’ve talked to in Gateway to College who said my story made them feel empowered to get through college—if I could do it, so can they. One day, it might be one of my own daughters who needs to read about what I went through so that she can have a little bit of hope for herself.

The biggest obstacle is me getting in my own way. Someone asked me recently if it is hard to be so vulnerable by publishing my story. I told her it’s one of the most emotionally challenging things I’ve ever done, while also being such a happy time. I burst out crying the other day when I saw my book on one of the front tables in a bookstore. I felt so incredibly happy, while also paralyzingly afraid. I am inspired by the memoir writers who have come before me, who I’ve been blessed to spend time with, who tell me to be brave, to write courageously, and to write my truth.

Where have you seen experiences similar to yours reflected in fiction or in other media?

I love Reservation Dogs so much! While I wasn’t raised on my reservation, I’ve spent some time there, and I’ve spent a lot of time on reservations in Washington and Oregon, as well as other parts of the country. I also did not grow up well off, and a lot of my friends growing up lived in dire poverty. My brother grew up on our reservation, and I stayed with him a lot in a trailer his girlfriend’s mom owned when I lived in South Dakota.

I am also very drawn to Tommy Orange’s work. He is so humble in his writing and in person, but it’s brilliant work that really resonates with my experiences. Pam Houston was also his mentor in the same creative writing program I went through. Trevino Brings Plenty is another IAIA alum whose work has inspired me since I was a weird 14-year-old Portland kid watching him perform poetry at the local coffee shop.

There is much hardship in your personal family story, not to mention the inherited trauma of Native peoples. Where do you find hope and lightness?

I have three bright lilies tattooed on my chest and arm to remind me of just that: to stop and smell the flowers, enjoy beauty just for beauty. I love creating beautiful things. I bead earrings and necklaces and lanyards, and I’m getting into pottery and painting. I like to decorate my surroundings with art and plants and earthy things. I love a big, heavy mug filled with coffee.

My biggest source of hope and lightness is my daughters. They are beautiful and smart and hilarious. They remind me to soak in the moment and be fully present. My favorite thing is to listen to their laughter. It is the most exquisite sound in the world.

Rebecca Foster