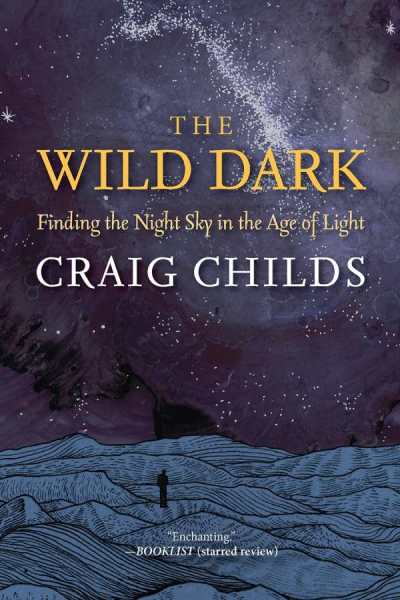

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Craig Childs, Author of The Wild Dark

“Light in excess is a toxin that disappears when you turn it off, easy as that.’’ —Craig Childs

You are a modern human living a life far different from your ancestors, and that’s cool if you break your neck and need a skilled neurosurgeon, but in the high-tech trappings of the twenty-first century, there are things that have fallen out of favor at great cost to our health.

We no longer walk on our bare feet, for example, which sounds like an advantage, but rubber soles keep us from tapping into the energy of the earth and exchanging positive and negative electrons to rid our bodies of harmful free radicals. And then there’s the sad fact that we no longer have a relationship with darkness and the starry night sky because of our excessive—call it an addiction—use of artificial light.

Like most addictions, too much light, without intermittent periods of darkness, is doing real harm to humans and countless species of animals. We learn as much from Craig Childs in today’s conversation with Rebecca Foster. Craig is the author—most recently—of The Wild Dark, a mesmerizing exploration of what we miss when we can’t see the night sky.

The Wild Dark earned a starred review from Rebecca in Foreword‘s May/June issue (free digital subscriptions), and with great nature writing on our mind, we’re excited to give a shout out to the winners of the 2024 Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Award winners in the Nature category. Patagonia National Park (Gold medal), Birding for Boomers (Silver), The Mourner’s Bestiary (Bronze), and Into Whooperland (Honorable Mention).

Why are we still afraid of the dark and the wilderness? Is the fear innate, or learned?

By definition, the wilderness is a thing we don’t control, and the same goes for darkness. These are places of unknowns, not engineered for our convenience. You’ve got to pay more attention and heighten your senses. There should be a touch of fear if fear is what sharpens your awareness. Sure, there are irrational fears and phobias, mostly learned, but I believe there’s a baseline of concern that’s higher in places where we aren’t the priority.

There’s a study where the startle reflex was measured in either light or dark conditions, and it was much higher in subjects in the dark, which makes absolute sense. You lose your usual reference points; you are not as aware of what you’re dealing with. We call it fear, but when you boil it down, it’s really awareness. We’re just not all used to having to be aware.

You link the ancient past with the present through the discussion of Ptolemy, who created an “early astronomy app,” and Indigenous peoples who navigated by the stars. Why do you think humans have always been drawn to look upward and interpret what they see in the sky?

If you didn’t know better, without astronomical sciences, you’d look up at night and think … what? Nothing up there resembles what we have down here with our feet on the ground among mountains and trees and people hustling about. Up there looks fantastical, unknowable. I wonder if the more supposedly intelligent animals like certain birds or sea mammals catch sight of the night sky and are bewildered. Seals have proven that they can identify constellations, so they are aware that something besides water and earth is happening. I think the same is true for us: we realize that something big is going on, it’s all around us, and we scarcely know what it is. Then you start detecting patterns, understanding how planets move against the backdrop of stars, patterns of eclipses, lunar cycles by the month and by the decade. What are we inside, some kind of giant, luminous clock? How could you not stare?

You undertook this trip [bike north from Las Vegas to one of the darkest places in North America] with your friend Irvin, a Forest Service employee (and fellow wilderness guide in Mexico in the 1990s). Why did you envision this as a two-person trip rather than a solo expedition?

I get tired of myself. Other people are so much more interesting. I do appreciate solo trips, but for this book having someone from the bright DC area helped give perspective. When Irvin told me that in the city he doesn’t really look up at night because, frankly, there’s hardly anything to see, that really struck me. He and I figured we’ve spent more than four hundred nights in each other’s company on the ground and under stars, so he’s a kindred spirit. Also, some of these crossings were vast. In case of a mechanical failure, we were each other’s backups.

The chapters move down the Bortle scale, from the most light pollution to the darkest skies. How did this structure suggest itself?

My original concept was to move from one end of the brightness/darkness spectrum to the next and the Bortle scale was an easy reference. I’d like to say I did, but honestly I didn’t plan the structure. It ended up happening that way, so the book followed along. I put a mark on the map for what should have been the darkest place and, looking at the terrain we had to cross, figured it would take about nine days to make two hundred miles. The Bortle scale has nine zones, and, fortuitously, each night matched up perfectly. I love it when writing works this way, when the story so neatly delivers itself.

I was struck by a statistic you quote: 80 percent of the world’s population cannot see the Milky Way. Urbanization is on the rise, and we often hear that city living is most efficient for ensuring access to resources and services. But does it necessarily mean a disconnection from nature? Will the night sky become something that’s only for the elite to appreciate?

I’m hoping people in the city will look up, or at least what I’ve written will nudge their gaze a little. I just got back from New York City and, because of writing this book, I’d find stars and a planet each night, and a bit of a waxing crescent moon between the buildings. There are darker places, parks, backyards, suburbs. The night sky isn’t completely out of view. A sky full of stars takes more effort.

In the book, I write about working as a guide leading school programs from Los Angeles into the desert for overnights about two hundred miles away from the city and it was stunning to see their reactions to a sky full of stars. I am a strong believer that if you see it at least once in your life, it will be with you forever. But you’re right, there’s a degree of elitism to having ready access. A dazzling night sky is a privilege, and it should be a right.

It’s sobering to learn of the unwonted effects of human light use on other creatures (such as the 9/11 memorial light beams being responsible for thousands of bird deaths). When you explain these interspecies conflicts, it seems quite obvious, and yet we’re mostly unaware of them in the day to day. How can we get away from our anthropocentric mindset?

That’s the big question, isn’t it? How do we see beyond ourselves and recognize the impacts we have on those that aren’t us? I wish I had an answer other than appreciation and observation, but that’s all I’ve got. See what’s out there beyond our humanity and what we do to it. Open up, pay attention.

There’s a hopeful message here in that light pollution has an easy fix: turn the lights down, or off, and the problem stops (unlike other environmental issues with baked-in effects or feedback loops). What changes can readers effect in their own homes, and how can we also influence policy?

So many! Be aware of what light is emanating from your home through windows or outdoor fixtures. It’s called light trespass when you are forcing it onto someone else. Timers, dimmers, motion sensors, and shields all help. Look for warmer, softer lighting outside rather than glaring white spotlights. Mention to a neighbor that a light is shining right into your bedroom and see if there’s something that can be done. Stand up at community meetings with policy makers and say you want better, more thoughtful lighting that doesn’t degrade the night sky. Light in excess is a toxin that disappears when you turn it off, easy as that.

Rebecca Foster