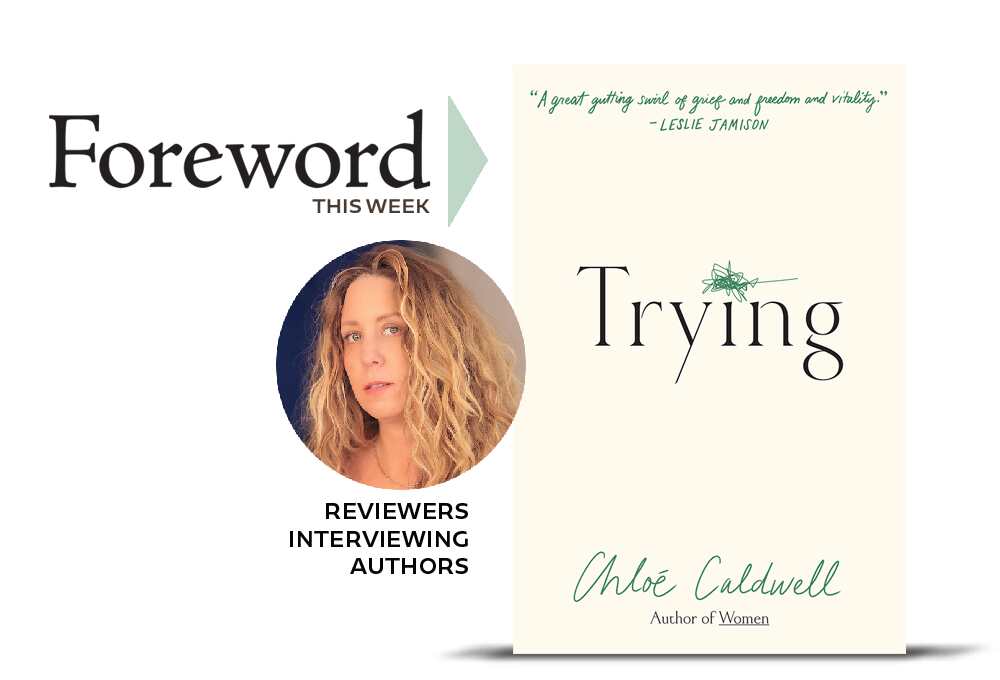

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Chloé Caldwell, Author of Trying

“Once you remember your queerness, the world opens up. The options abound. My life felt like it was closing in on me when I was in a heterosexual marriage. Now I feel like I can do anything. Good things are on the horizon.’’ —Chloé Caldwell

Chloé Caldwell’s gobsmacking quote above reminds us that writers are some of the most courageous people on the planet.

Not all writers, of course—we’re familiar with plenty who write beautifully but have very little life experience to keep our interest. But in today’s interview with Rebecca Foster, Chloé makes it clear that she’s not afraid to live in a world cracked wide open. She feels and acts like she can do anything because nothing intimidates her. Which is one thing: finding the guts to write about it for all to see—well, that’s another level. Chloé, we stand in awe.

In her starred review, Rebecca calls Trying an “intrepid memoir that documents shifting desires by interlacing infertility and queerness.” It is a book that confirms our suspicion that certain people are looking at a far different horizon than the rest of us.

The following four INDIES 2024 works of LGBTQ+ Nonfiction also deserve your attention—How Do I Sexy? (gold); Transgender Justice in Schools (silver); No Son of Mine (bronze); and Virginia’s Apple (honorable mention). Digital subscriptions to Foreword Reviews are free.

What are some of the various connotations you hoped to convey with a title like Trying?

It wasn’t my first title. The first title was “36 Notes on Trying.” It was an essay. From there I remembered the phrase “Orphaned Passages,” which my editor Yuka had used when giving me revision notes on my previous book. She’d said, “there are some orphaned passages that need to either be cut or find homes. I liked the idea of doing an entire book of orphaned passages. So I made the title “Orphaned Passages: Notes on Trying.” That’s the title I sold it under. Over a year or so, I realized people were referring to it as “the trying book” and by people I mean me and Yuka and the Graywolf team. “Orphaned Passages” was a little too abstract and confusing, plus hard to say. Whenever I said it, people didn’t know what I was saying.

I had to chuckle at your wish that you could shoehorn in a nature allegory, such as has become common in women’s memoirs (wild swimming, falconry), to elevate the narrative. How did you settle on “writing what you know” (retail), and was there some defiance to that?

Pretty early on in the writing I brought in the life-changing pants store, just because I was there a lot so it was on my mind. I’d also noticed a trend or pattern in books where the narrator or protagonist who was writing the book was also a writing teacher or professor. I knew in Trying I’d bring in some of my teaching stuff, but I missed the days when writers had (and wrote about) basic everyday life and jobs, like being a barista, working at the Gap, working in a bookstore as a cashier. So I just thought, what the hell, let’s see if it works.

In Act I, you’re married to a man and undergoing IUI; by Act III, you’re dating women and reconsidering your options. How did your concept of the book you were writing adapt in response to your changing circumstances? Does envisioning a life as structured into acts influence the retrospective appraisal of events?

The three acts came in much later in the process. I’d thought it was going to be a straight through book of fragments. Once my circumstances changed overnight, I had to figure out a structure that would reflect the shift. I thought about it being in four parts, two parts, and ultimately went with three acts. I don’t know if it was the right call, but I committed to it. My aunt recently said about Act 3, since the tone changes so much, that the book is like BOGO. Buy one, get one.

More than a decade before all of this happened, you’d published your “queer novella,” Women. Looking back, how do you account for that? Is it ironic? A self-fulfilling prophecy?

I wrote Women when I was twenty-seven after an affair I’d had with an older woman that destroyed my brain. I knew I was queer and after that went on to date various genders. Then I met the person I married, and the queerness got more and more repressed, sadly. But what’s really wild is that Women was out of print during the years I was married to a man. The rights reverted back to me. A few months after we went our separate ways, coincidentally, my literary agent sold a reissue of Women to Harper Perennial and it became a bestseller. You can’t make this stuff up.

Trying is written in the same fragmentary style as Women. How does this reflect your composition process and influences, or contemporary preferences?

Every book I write finds its own style. I have two essay collections and a memoir that don’t do the fragmented white space thing. Usually, I just begin writing and see what structure emerges. Then I lean into whatever I’m already doing, because I believe our subconscious is the creative one. In this case, like I said about the title, I had envisioned the book as “notes” because I loved the book Notes to Myself, by Hugh Prather.

A friend suggests to you that writing is the longest relationship you’ve had. What does it mean to you to make a vocation into a partnership?

It’s the best. My dad passed away last winter and you might say that music was the longest relationship he had. He’d even written a book about five years ago about his relationship to music. Nothing has been quite as consistent and life-giving for me as writing has.

The book doesn’t offer closure on your (in)fertility journey. How did you decide where it would end? Is there anything you’d want readers to know as a postscript?

Once you remember your queerness, the world opens up. The options abound. My life felt like it was closing in on me when I was in a heterosexual marriage. Now I feel like I can do anything. Good things are on the horizon.

Rebecca Foster