Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Linda S. Svitak, Christin Jaye Eaton and Lee Svitak Dean, Authors of Kitchens of Hope

“It seems that current immigration policy is driven by fear more than reality. For example, immigrants are being rounded up at workplaces such as farms, meat processing plants, and hotels to be sent to other countries. This aspect of the program undermines the notion that the deportation activity is intended to remove criminals and non-productive people.’’ —Linda Svitak

This week, we return to the topic of immigration—and we will continue doing so periodically with the hope that our immigrant friends and neighbors may live without fear of being arrested, deported, or worse.

There’s no doubt the issue of immigration is complicated—we are a nation of laws and the laws regulating how to visit and attain citizenship in the US are clear. But we are also a nation of rights and procedures. If you are within the borders of the United States, you have rights to due process (5th Amendment) and equal protection (14th Amendment) no matter your immigration status. In nearly all cases, you also have the right to a hearing before an immigration judge. What’s happening right now with expedited removals is an outrage. We can do better.

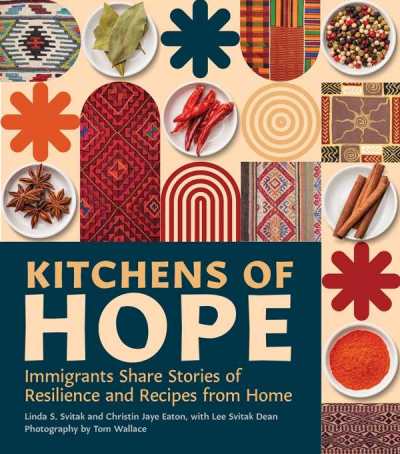

Today’s featured book, Kitchens of Hope, is a delightful sampler into the myriad ways immigrants enrich our country: intellectually, economically, and gastronomically. After reading her Foreword review, we asked Rachel Jagareski to engage with the three authors—each coming from Scandinavian backgrounds—to learn more about some of the families and foods that make this one of her favorite cookbooks of the year.

We’ve recently seen a few other very special cookbooks including these 2024 INDIES winners: Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World’s Largest Syrian Refugee Camp (gold); Nosh: Plant-Forward Recipes Celebrating Modern Jewish Cuisine (silver); The Vedge Bar Book: Plant-Based Cocktails and Light Bites for Inspired Entertaining (bronze); Æbelskiver: A New Take on Traditional Danish Pancakes (honorable mention). Digital subscriptions to Foreword are free.

Kitchens of Hope contains treasured recipes from around the world but it is the storytelling by immigrant cooks that make this book so powerful. How effective is conveying personal stories as a tool in combating anti-immigrant bias and swaying public opinion?

Lee: Personal stories are critical in understanding immigration, as well as many other topics. When all we hear are stark numbers, which is often the case, the immigrants and their lives do not seem real for many of us. And to be effective, you not only need stories but also photographs to show the faces of immigration, the humanity of those who are coming here. The personal is political—and it can be effective.

The stories in Kitchens of Hope—and elsewhere—also provide important context that reflects immigrants in real life working and making a difference in their communities. These stories are a counterpoint to the false narrative that immigrants are a danger to a community. In our book alone, we have nurses, teachers, translators, doctors, chefs, immigration lawyers, administrators, and so many more who have something to offer, including leadership and community building. Those are the stories that need more attention to counter the fear of those who are different from ourselves.

Christin: Telling personal stories offers a powerful chance to persuade others of the full humanity of our immigrant neighbors.

Coming alongside these travelers makes it hard to dismiss them as abstract ideas, threatening caricatures, or looming statistics. We learned that Haydee, a lawyer and police investigator in El Salvador, fled gang violence with her family and found a miracle here; we stepped behind Maiyia to avoid hidden landmines, then landed in Michigan with her family, wearing sandals in the snow. We looked over Mehmet’s shoulder as he sat, mesmerized, poring over massive law texts and realizing that his family faced ethnic discrimination; and we shared Omar’s memory of his grandmother inspecting banana peels for the clay mole pot, then saw how he was part of a cooking revolution in Minneapolis schools. Those stories made a difference.

Linda: The contributors’ stories tell us who these people are. What we learn from the stories is that immigrants are essentially like those of us who were born here. They love their families, children, and parents. They strive to better their lives through thoughtful planning, perseverance, and hard work. Significantly, many have made the most of the opportunities America afforded them by furthering their studies and advancing into professional careers, including law, medicine, and business. All of the contributors hold jobs, pay taxes, and make a positive difference to our community and to our nation. It is vastly important for everyone to know that the widely negative portrayal of immigrants in certain segments of the media and public figures is inaccurate and does all of them—and us—a disservice.

As the introduction points out, many of these stories reveal hitherto unknown details about the challenges of life back home and in adapting to American culture. What are some of the most surprising things you learned about these long-time friends, colleagues, and immigrant clients?

Linda: As Kitchens of Hope highlights, resilience reflects grit and determination, as well as the courage to move forward. I saw these traits firsthand in friends and colleagues in ways I could not have imagined. The wife of a business colleague came to the United States from Cuba as a fifteen year old, unaccompanied and in charge of her twelve-year-old sister, as part of a covert program by the US State Department and the Catholic Church to help children after the rise of Fidel Castro in Cuba. She and her sister did not see their mother for twenty years. In another example, a fellow parent at my children’s school took on the leadership of the tribunal in Guatemala, her home country, that searched for those who had been forcibly taken. This is courage. A co-worker on a service trip spoke of how she survived war in Sierra Leone as a child and went on to help resettle her family in the United States. She completed her education and has had a career at several major financial institutions. This is resilience. These conversations were not ones that came up in casual moments, but only as part of a deeper discussion on their journeys as immigrants. It was an honor to be trusted with these stories and others in the book.

There have been ebbs and flows of xenophobia and nativism in American history, but what are some of the socio-political factors behind the recent resurgence of anti-immigrant sentiment?

Linda: The world is full of crises—wars, famine, drug violence, climate change affecting people’s livelihoods. Large numbers of people have been displaced and are on the move. Immigration is, in part, a consequence of these pressures.

Many factors impact today’s anti-immigrant sentiment, one of which is economic anxiety. The pandemic and rising inflation, among other issues, have stressed many countries, not only the United States. Most societies have blamed immigrants for job competition and creating burdens on societal resources such as healthcare, housing, and public schools.

In addition, anti-immigration proponents frame immigration as a threat to our national culture and identity, claiming it somehow dilutes who we are as a country. Politicians proclaim recklessly that immigrants “hate America” and that they are “an invasion.” Respectful discourse is replaced by inflammatory language based on myths and misconceptions that fuel fears and anxieties to mobilize support for political agendas. Immigrants stand out because they look different, speak other languages, and practice non-mainstream religions. Also, immigrants generally have the least power and representation in society, making it difficult for them to deal with the persecution that they face.

Finally, while today’s immigration crisis is not the first for our country, it may be the most politically charged. Never before has mass deportation been the official government policy. It seems that current immigration policy is driven by fear more than reality. For example, immigrants are being rounded up at workplaces such as farms, meat processing plants, and hotels to be sent to other countries. This aspect of the program undermines the notion that the deportation activity is intended to remove criminals and non-productive people. Additionally, policy makers do not seem to have considered that the resulting job vacancies are not likely to be filled by the non-immigrant workforce in the United States.

We believe that there is a way ahead that will enable people to work together to obtain rational and compassionate solutions to our societal and economic challenges.

Culinary traditions are important touchstones for all of us, but especially for someone adjusting to a new country. What are some of your favorite recipes and stories from the book that demonstrate this?

Lee: One of the most significant historical time periods in my life was the Vietnam War, where I knew individuals who fought there or were protesters or conscientious objectors. The chaos of the fall of Saigon is particularly vivid in my mind, having watched it on the nightly news. We have three stories in Kitchens of Hope that tell the personal experiences during that time: from a Vietnamese woman who was five years old and whose family was picked up by a ship captain; from a Hmong woman who was four years old and whose father led a month-long escape for freedom with his entire Laotian village; and a young Hmong man who was born in a Thai refugee camp, where his parents met after fleeing from soldiers. The trauma and dangers of those years became even more clear to me with those individual family stories.

As for the recipes I use, I’m particularly drawn to those that include herbs and spices that were new to me. The fragrance alone of many of these dishes makes them standouts.

Christin: Many participants shared a longing to recreate in this country meals from their first homeland. Some like Shereen, Margaret, and Jose grew up eating, not cooking, so when they wanted to taste their memories, they made calls to their homeland, consulted countrywomen, or experimented here. I am inspired by their ingenuity. Nazneen found in her home health-care business that elders requested providers from their own home country, hoping for the chance to taste foods of their youth. This helps me remember what a luxury it is to cook and eat what you wish. Halima and Mariam founded a business so Somali mothers could earn a living while preparing the savory sambusas they grew up making. Yia opened a restaurant that illuminates Hmong food as a love letter to his parents, and Stine crossed the ocean to start a “waffleution” in a much larger country than her native Norway. The range in these pages makes me dizzy. All participants shared recipes that evoke home for them, so this collection is rich in both special dishes for celebration and simple meals of daily sustenance.

I was moved to learn about the Mongolian Lunar New Year celebrations from Delgermaa. For these traditionally nomadic people, the end of winter and the coming of spring signal safety and reunion. Family and friends gather, greet one another formally and share their joy at overcoming the harsh and heavy winter. And, of course, they share food. Through Delgermaa’s recipe offering, we too can delight in these savory steamed dumplings. And we can cap the meal with our choice of holiday cakes found in these pages: Eight-Treasure Rice Cake from China, Walnut Cake from Latvia, Tres Leches Cake from Mexico, or Lucky New Year Cake from Greece—take your pick! I for one am so grateful to have expanded my cooking and tasting experiences in such delicious new directions.

Some of the cooks featured in your book have made their traditional foods into a thriving business, like Halima from Somalia with her sambusas, and Yia who cooks Hmong dishes in his restaurant. What makes the food industry such a successful business model among the immigrant community in Minneapolis and elsewhere?

Lee: In the past there was a low bar to entry in the food world, whether it was farming, markets (grocery stores or farmers markets), or restaurants. Many immigrant families turned to this line of work where their entire extended family helped support the business through hard work and long hours. These jobs served as an opportunity for those who didn’t know a language and were in a new land. This was popular not only with fellow immigrants, but gradually with an extended clientele who learned to love the new menu offerings. While the business end may be more of a challenge these days, the interest in new foods by many Americans has provided a broader opportunity for immigrants to successfully offer a taste of their homeland. Halima of Somalia has a sister, Mariam, who had come earlier to the United States for graduate school, and together they started their sambusa-making company. Yia Vang had cooked for years, earning his position today as a chef in his own restaurant, as have Gus and Kate Romero, all of whom have been nominated for James Beard Foundation awards. From farms to restaurants, immigrants find opportunity for success.

The thematic final chapter focused on food as a key component of celebrations shows off delightful recipes and stories from South Africa to Bosnia to Mexico. It was inspiring to read about all the connections and traditions that food brings to a holiday or other festive gathering. What are some of your own celebratory food traditions?

Lee: Linda and I are sisters who spend holidays together, so our traditions are much the same. Reading the stories of our contributors reminds us that we are all immigrants and that our heritage and traditions survive despite the passage of time. We are Norwegian (though she married a Swede) and a few Scandinavian specialties have become our standards, particularly over the Christmas holidays. That includes sandbakkels, a shortbread-like cookie made in a fancy tin, and lefse, the potato flatbread, both of which find a place at the table (and I teach cooking classes for both at Norway House in Minneapolis). I also make meatballs (admittedly, Swedish ones!) at the Christmas holidays with lingonberries and quick pickles, which taps into the Scandinavian tradition of fermentation. Our Christmas holidays would be a little less bright without the foods of our heritage that have been at the table for more than a century.

Christin: As I grew up, Christmastime meant big extended-family gatherings. The side pantry filled with maraschino cherry bars, melting moments, sandbakkels, nut tarts, toffee, peanut brittle, and scrabble—our homemade version of Chex Mix, jazzed up with mixed nuts, Bugles, Worcestershire sauce, and celery salt. In a lucky year, we might find a box of fresh Colorado peaches. Quick breads in many flavors were set out on cutting boards in the kitchen. On Christmas morning we sat together and opened our mountain of beautifully-wrapped presents, then an egg-and-sausage casserole kept us full while the turkey and stuffing baked.

As for me and my three children, who have begun to have children of their own, our most iconic meal is lettuce wraps. We started this “tradition” on a weekday evening when everyone could come together, filling the house with conversation and laughter and little ones running. Many years ago, I found this recipe in the pages of the Taste section of the Star Tribune. This dish can be adapted with meat and vegetarian versions coming together seamlessly, side-by-side. Chicken, chickpeas, or baked tofu cubes are stirred separately with fresh ginger and garlic, spiced with crushed red pepper, and sauced with peanut sauce, soy sauce, and lime juice. Assembled in lettuce leaves with steamed white rice, topped with diced sweet red peppers and finely chopped peanuts, this meal makes everyone happy. It’s always a good thing when it is a lettuce wrap night!

Rachel Jagareski