Reviewer pine breaks Interviews Walter Marsh, Author of The Butterfly Thief: Adventure, Fraud, Scotland Yard, and Australia’s Greatest Museum Heist

Keep your hands off my butterfly, you arthro-poaching, science-setbacking, advantage-taking scoundrel. Alas, crime knows no bounds.

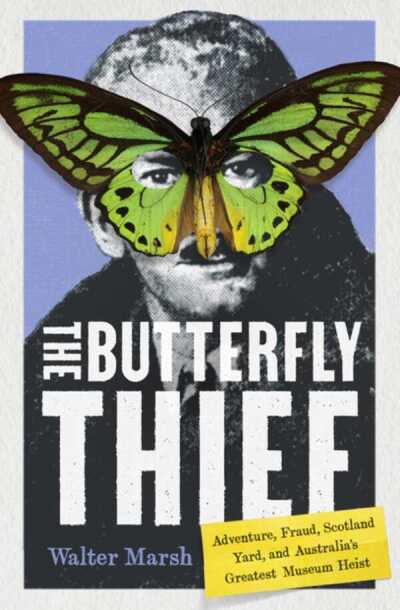

So, yes, a theft involving butterflies, as farcical as it is infuriating because robbing museums is even lower than stealing purses from old ladies. And yet, the true story detailed in The Butterfly Thief has all the riveting elements of a Hollywood blockbuster, with a sexy Down Under accent. Pine breaks reviewed the book in Foreword’s November/December issue, and Adelaide-based Walter Marsh was happy to answer a few of his questions.

The focus of the work is one of its strengths. What was one of the defining moments that made you realize this book needed to be written, and how did that awareness shape your framing of the subject matter?

For the past few years I’ve bounced between the museum world and journalism, picking up all kinds of stories and histories about colonisation and museums, both in Australia and across the British Empire, that left me with a sense of responsibility to share them with a wider audience.

Whether that was a series of articles, or a book, I wasn’t quite sure, until I started working at the South Australian Museum and heard this story of an English gentleman collector Colin Wyatt who was welcomed into Australia’s museums—and seemed to fit right in—only to go back to England with many of their treasured butterflies. I’m not the first person to be intrigued by the story, but for me it flipped the script on those mythologised colonial histories of great men who for centuries went out, explored, and studied the world, then brought all this stuff back to museums at home. It was a story that offered a way to draw general readers into the complex world of museums, with the momentum of a true crime story not unlike Susan Orlean’s The Library Book. Also, Colin Wyatt was such a compelling, intriguing, and at times inscrutable character that the story seemed ready to write itself.

How did you navigate the balance between presenting the technical and archival material while still making it accessible to a broad readership without diluting the deep research?

There’s nothing I love more than diving into an archive, turning over every page, and really soaking up every scrap of information I can find. At first, you’re desperately digging around, wondering whether you can possibly find enough material to string together a basic narrative. By the end, you’re unceremoniously cutting things that, when you first read them in a library somewhere, left you pumping your fist in silent delight. But, if they ultimately don’t add much to the clarity or momentum of the story, then it’s into the bin.

Trying to balance those impulses is a real challenge—to make the reader feel immersed in the story and the world it takes place in without the place-setting feeling too labored or indulgent. I think in today’s media landscape, you have to be conscious of readers’ attention spans, and really treat it like the scarce commodity that it is. In effect, that means whenever I include something, I try to ask myself: what’s the pay-off for the reader if I put this in?

The narrative moves between multiple settings, characters, and time-periods. What guided your choices of when to zoom in on individuals versus when to step back and offer broader context?

My books do tend to jump around a bit, with different timelines and characters, but I always approach it with a pretty clear structure and intent—everything has to either have a connection to a few core figures, or really contribute to the broader themes of the book.

For something like butterfly theft, which can seem kind of esoteric compared to jewel or art heists, one of my challenges was to convey to readers the value of these collections, and the transgressive nature of the theft. That meant trying to capture the scientific, historic, and sentimental value of these collections to the institutions and the people who first collected them, which meant investing time into both the bigger sweep of history, but also the smaller personal stories of the individual collectors who make up that inter-generational lineage.

The first part of the book really deliberately bounces back and forth between those stories, and the life of Colin Wyatt—who we know from the outset will be revealed as the chief suspect (he’s on the cover, after all). But by structuring in this way, my aim was that by the time Scotland Yard catches up with Colin Wyatt in England, I’ve also caught the reader up on the full history of the museums he stole from—and also revealed that the people we thought were the “good guys” at the start are actually complicit in some pretty dark stuff themselves.

In your research what was a discovery or insight that surprised you or shifted your relationship to the material?

I had a pretty good idea of some of the colonial stories I wanted to include—like the Benin Bronzes at the South Australian Museum, and the legacies of the famous naturalist Sir Joseph Banks—but even I was surprised by some of the dots that linked up. For instance, I’d read about a man named John Roach, the first trained taxidermist/collector to be hired by Australia’s first and oldest museum museum, the Australian Museum. Roach was already a convict, and a pretty colourful character, but when I typed his name into a newspaper database the sentence, “I was a little behind that morning with Roach the bird-stuffer, when the Natives came on the camping ground” came up.

This was from an official enquiry into an infamous massacre that occurred on an 1836 expedition, and the fact a museum worker was there that day armed with a gun, was something I hadn’t encountered in any museum histories. The fact this same expedition later brought back a wealth of new species for the museum really illustrated how the violence of the colonial project, and the work of natural history, was entwined from the outset. And it was just sitting there in plain sight.

What sources, stories, or perspectives did you want to include, yet ultimately excluded? What made you decide to omit them?

The final third of the book had a few chapters that took a more contemporary view of Australia’s museums, from the work of First Nations communities to repatriate Ancestors from museums around the world, to the impact on descendants of British conquest in West Africa whose spoils now sit in faraway institutions.

I also travelled across several states to visit another man who served a prison sentence in the 2000s after being convicted of taking specimens from the Australian Museum while working there. His story was absolutely fascinating, but in the end I realised that for this book, I needed to bring the focus back to Colin Wyatt, and took the fact that I was okay with leaving some pretty compelling material on the table as a sign it was the right choice.

The work is a commentary on the nature of museums and how they function. Can you reflect on how your thinking about this has evolved from the start of the project to now?

This project has brought me into more public museums and collections, and introduced me to more experts and present-day museum workers than ever before. It really highlighted the passion and hard work found across these spaces to push science and cultural understanding forward, while also reckoning with the histories of these institutions at a time when resources are extremely stretched and occasionally facing political pressure. But they still welcomed me in, let me look at their archives, ask silly questions, and put together a story that is at times quite unflattering. But this is what state cultural institutions are there for; flaws and all, they’re the custodians of memory and knowledge, that’s there for researchers and the public to use in ways that their original collectors could never have anticipated.

pine breaks