Reviewer pine breaks Interviews Be Steadwell, Author of Chocolate Chip City

Prepping for this interview with Be Steadwell got us thinking about Black sisterhood—that powerful, evocative, edgy, and exclusive club of women friends who see in each other the nerve and determination to overcome a world set on destroying them—as in, I got your back, sister.

And while lots of communities of women have attached themselves to the moniker of “sisterhood” over the years—think of the white feminist version in the 1970s—the Black/women-of-color lens we now associate with the term gained a great leap forward when Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and other Black women formed “The Sisterhood” in 1977 as a monthly gathering of Black women writers in Brooklyn.

Audre Lorde was part of The Sisterhood and Harvard professor Durba Mitra credits her with strengthening Black sisterhood by distancing it from white American feminists with their ties to colonialism, systems of racism, and white heterosexual patriarchy. Quoting Lorde, Mitra recognized that this new vision of sisterhood was based on an “explicit alliance across oppressed Indigenous, colonized, and Black women to sustain the possibility of living: ‘we are sisters, and our survivals are mutual.’”

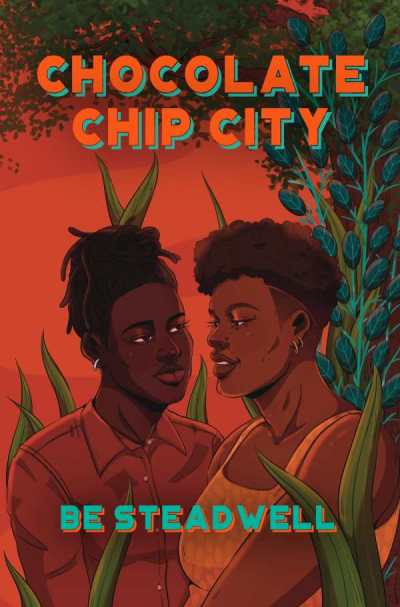

Be’s splendid Chocolate Chip City—which she describes below as a “mix between trashy romance novel and a deep spiritual, historically grounded, black queer love story”—features the three Jones sisters, Ella, Jasmine, and Layla, raised by their mother to know that “their power comes … from their sisterly bond and their ability to heal, connect, and resist,” to quote from pine breaks’ starred May/June review for Foreword. Seemingly, Be is reminding us that the idea of sisterhood extends from maternal strength. Brava!

Four other standout LGBTQ+ novels recently won top honors in the 2024 INDIES Book of the Year awards: The Cadieux Murders (gold); Sweet Tooth and Other Stories (silver); A Wounded Deer Leaps Highest (bronze); and The Black Bird of Chernobyl (honorable mention). Would be readers of Foreword are entitled to a free digital subscription.

For anyone encountering Chocolate Chip City for the first time, in your own words, how would you describe your debut novel?

I would describe Chocolate Chip City as a mix between a trashy romance novel and a deep spiritual, historically grounded, black queer love story. It’s hard for me to pinpoint what this story is in the context of things, but … I think I wrote it because I wanted a book with sex, magic, queerness, Blackness, and poetry. So what I created is an attempt to have all of those things in one piece.

Each of the Jones sisters has a distinct identity and struggle. How did you approach building such layered individual characters while maintaining their powerful collective dynamic?

I have sisters. I was inspired by their power and their stories. The biggest challenge that I’ve seen in my life and in my siblings’ and my chosen family’s lives is that you can have power and you can have magic. You have this ability to create. It’s not as simple to say “oh, I’ve realized I can fly and now I’m going to go fly.” It’s complicated, but nobody cares. Or, I don’t have the resources to do body work. In capitalism, what do you do with your magic? The struggle is not “Am I magic?” But how do I control my magic? What do I do with my magic in a corrupt capitalist white supremacist world.

Sexual identity and body image are explored with honesty and nuance in the work. How did your own experiences or observations inform how you portrayed queer intimacy and fat positivity?

In terms of fat positivity, an influence that means a lot to me is Sonya Renee Taylor, who wrote The Body is Not an Apology. I think just learning how to love your body, accept your body, celebrate your body in a world where everything you see is telling you that you’re wrong, unhealthy, ugly [is important]. I’ve experienced that firsthand and folks in my chosen family and [biological] family have experienced those things. It felt important to me to write a character who was a few steps past the realization that yes, she’s fine. She’s FTWhot. She can date. She can have a good time. Sometimes she still has those feelings because she has feelings, because this is where we live.

With the gay sex scenes, was there a desire to shock or just simply portray this is how it is from your perspective?

Oh, no, I wasn’t trying to be shocking. I wrote queer sex that I thought was hot. There was a point where I thought to myself, “oh, I could write this in a very poetic, sort of subtle [way] which would make it highbrow and not erotica.” But I really like erotica, and I really like to see everything, or to show more. It sort of reminds me of when you watch a sex scene and often with queer sex scenes, you’ll see them kiss and then there’ll be some heated moments and then it’s the next day and we’re like, wait, we don’t get to see anything. This is such an exciting and rare thing to see in mainstream media. So if I just left it up to metaphor and poetry, I think it would miss some of the fun.

Mama Ro is a powerful matriarch with her spiritual, artistic legacy. What role do elders and ancestral memory play in shaping the narrative’s magical realism?

Mama Ro feels like a mentor, a teacher, a priestess. She does a lot of things and the main thing that she does for her daughters is connect them to history to Black history, the kind of history that you wouldn’t learn in school or just stumble upon. That history allows the sisters to connect more deeply with spirit ancestors for their own power, their own abilities. I think that intergenerational connection is really beautiful and important and it’s also something that feels hard to find in real life because I think we are so different from our parents.

Washington, DC is an important character in the book. Could you talk about what the city represents to you?

DC is where I was born and raised. It has always been a dynamic space for me. I grew up going to a pretty rich kid’s private school like the sisters did and so there’s like this element of wealth and whiteness, white liberal folks. And then there’s Black culture that’s everywhere because the city is historically Black. You have soul music, you have go-go music. You have echoes of the past. Everywhere you look, you’re seeing fewer and fewer Black people and people of color in the city because it’s become unaffordable.

What were big defining moments growing up in Washington DC? What scenes or people or places really resonate, that define your time growing up in Washington, DC?

So, they used to host go-gos at fancy private schools on the weekends to make money. It was like the weirdest thing. People would hire, I don’t know if maybe some folks like rented these gymnasiums. It was basically a dance. The band was all Black. Everybody who came to the go-gos was Black. We would go as fourteen-year-olds, and I mean, high security because they’re like, oh my God, “there’s Black teenagers uptown.” You go in, it’s dark. The band is amazing. The music is good. And you just dance all night and try to [get] people’s numbers and stuff. I talk about that in the book through Layla’s perspective, and that was one of my favorite experiences in high school.

Another one that comes to mind is my first gay pride. I was also in high school. DC has a pretty big gay pride parade and celebrations and that was the first time I got to see a lot of queer community in person, being joyful, celebrating, laughing—just the joy of it. It made me feel so connected, in a way that I hadn’t just with my little high school girlfriend or whatever.

Also, the woods. Rock Creek Park is a park that runs through the city and just spending time with the trees. I tried to bring the trees and the woods into the book as well, because it feels like such a spiritual place, the woods. Rock Creek, it’s not a created park, it’s just what was there, and it’s preserved. The land is old, and it feels powerful, and I still go in there and spend time when I’m in Washington [Be has lived in Baltimore for the last two years]. That was a beautiful memory from being a kid.

And the museums, I also put that in the book. All the museums on the mall are free so you can go see really gorgeous art museums for free. I went often with my mom. I think being able to see really powerful art as a kid really influenced me and inspired me, and it also helped me shape my aesthetic, my style as an artist. I think I learned what I really liked to see in those spaces.

If a reader were to walk away with just one lingering thought or feeling after reading Chocolate Chip City, what would you hope that would be?

I would hope they would walk away with the feeling of joyful Black women. Black women feeling at peace and joyful.

pine breaks