Reviewer Peter Dabbene Interviews George Takei, Author of It Rhymes with Takei

We’re joined by a film star this week, one of the Star Trek actors who captured our attention in his role of Lieutenant Sulu in both the television and movie series. But don’t think George Takei rested on those laurels. In 1994, he launched a writing career with a memoir and has since written (or contributed to) several more books including two graphic novels that recount his experiences in Japanese internment (concentration) camps in the US during WWII. Moreover, after coming out in 2005, Takei became active in California’s LGBTQ+ community and contributed to the Human Rights Campaign’s Coming Out Project as a spokesman.

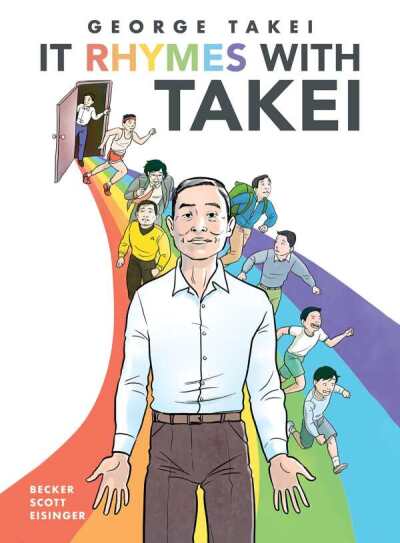

Takei’s latest graphic novel, It Rhymes with Takei, broadens its scope. In his starred Foreword review, Peter Dabbene calls it the “outstanding graphic autobiography of a principled man who became a cultural icon because of his passion for improving the world for others.” As you might expect, said reviewer was quite thrilled to connect with the legendary actor and author.

Four other graphic novels deserve your attention—all winners in the 2024 INDIES Book of the Year Awards: Age 16, by Rosena Fung (gold); We Called Them Giants, by Kieron Gillen and Stephanie Hans (silver); Ruth Asawa: An Artist Takes Shape, by Sam Nakahira (bronze); Between Two Sounds: Arvo Pärt’s Journey to His Magical Language, by Joonas Sildre (honorable mention). We encourage you to take advantage of a free digital subscription to Foreword Reviews.

It Rhymes with Takei is a graphic memoir. There are many advantages to this format, including the cliche “a picture is worth a thousand words.” What made you decide to tell your life’s story in this format? Were there any specific aspects of your story that you felt were better suited to a visual interpretation?

I thought that by using the graphic memoir format, we could more clearly visualize the feelings that I felt. I was in my closet, I was hiding my true emotions, but with this format, we can both describe how I felt as well as show how I felt. I use the phrase “silent harassment,” because when you’re in the closet, people would make assumptions. They would show their disgust or disparagement of LGBT people, plainly, right in your presence, assuming that you’re like them. And because you’re hiding who you are, you have to grit your teeth and tolerate it without responding. And so the graphic memoir gives you that double communication, visually as well as the internalized feeling.

You might almost say that you were living a double life. So comics are appropriate, as a kind of double storytelling.

Well, yes. It’s the same life, but a double interpretation of how we’re living. Our facial expressions would be “normal,” but inside, you’re raging or you’re feeling humiliated or embarrassed. I can use words that describe how I felt physically, and they communicate, but sometimes visually, you can communicate that feeling much more powerfully. The electric, spiky sensation of goose pimples going all over your body.

Your last graphic memoir, They Called Us Enemy, dealt with your family’s internment in American prison camps during World War II. Both that book and this book, It Rhymes With Takei, seem like they must have required a great deal of soul-searching in order to translate your life experience into a narrative. Was one of these books more difficult than the other?

In my first imprisonment, told in They Called Us Enemy, I was a child, and I didn’t fully understand what was happening. Later on, when I was a teenager, my father answered my questions about those years that we spent behind US barbed-wire fences. So that book is mostly presented through a child’s eyes, through the simplicity of a child’s experience. But the second graphic memoir, It Rhymes with Takei, was more difficult, because it covers a larger span of time. It covers my second imprisonment, behind the “invisible barbed-wire fence” that I lived in for sixty eight years: the secret of being gay. So this book was much more substantial and therefore, much more challenging. It deals with more complicated emotions.

Did either book give you more personal satisfaction to complete?

That’s difficult to respond to, because they were both satisfying. It’s my thought that Americans don’t really know American history. And I want these books to help preserve that history. So I do think both books are fulfilling, each in its own way. And I can’t say which is more … profound than the other. They’re both profound.

It’s a testament to you and your team (art by Harmony Becker, adaptation by Steven Scott and Justin Eisinger) that these books work so well, combining art and text to deliver a unique reading experience. Were you aware of the growth that graphic novels have taken in the literary world over the past twenty years or so?

Oh, most certainly. I realize now: comics can deal with adult topics, like my seeing this terrifically built guy at the bathhouse. We can do that now, which would be unthinkable when I was a kid discovering comic books. So yes, we’ve made good progress … I think in almost all of the areas of the arts. In movies, certainly, we can now visualize what was once considered risqué. For example, when I was growing up, in the 1950s, married couples in movies slept in twin beds. Now they can sleep in a double bed! Something as simple as that. We can show much more, and be more honest.

Were you a comic book fan as a kid?

Well, I became a fan. We were denied everything as I was growing up. It wasn’t until I was about nine that I discovered comic books, along with technicolor movies, radio, and this whole outside world. We were in a prison camp, denied everything. Even with food—

I’m a terrible example of a Japanese American because I don’t use chopsticks properly, because we never had chopsticks when I was growing up. It was always a fork and knife and spoon in the mess hall. And so I’ve been embarrassed when I’ve dropped things or flipped my sushi across the table! But when we got out of the camps, my father brought home comic books, a portable radio, and took us to movie theaters. There was this sudden flood of colorful lights, sounds, images … culture that could transport me to other places. It was absolutely mind-blowing.

You have run for elected office and served in local government appointments, such as the Southern California Rapid Transit District board. You’ve also been influential as an activist for many years—a leading model for how much can be accomplished by someone who’s not in political office. Do you ever see yourself running for office again? Do you think you’re more effective as an influencer?

I realize now how strenuous it can be to be in public office. It’s a young person’s calling, and I’ve got a lot of miles now! So I think the passage of time has taught me to focus on making the best use of the platform that I have today, outside of elected office.

One of the most moving and memorable scenes in It Rhymes With Takei is a visual metaphor that shows you coming out of the closet as gay at age sixty eight, but only after a lifetime of walking down the corridor that leads to that door. It’s much more truthful to many people’s experiences than a simpler visual metaphor that only shows the actual opening of a closet door. Can you take us through your thought process in creating this sequence?

By the time I’m thinking of coming out, I’ve gained some control over my life, but at the same time, I’m not prepared for the dramatic flood of changes that’s going to come. And so that long walk down the corridor is a very limited, dark space. It allows for some light to come in, and you get an idea of what’s beyond that corridor, but not the whole thing. And then you go a bit further and you add more exposure, and you get more light coming in and more knowledge, and then the final stepping through the door, which brings the whole flood coming in. And that whole flood is overwhelming.

You really hadn’t prepared for that much, and it takes a lot of adjustment and creative response to the flood of light. In the same way that when you have that bright California sunshine suddenly on your face, you have to make a physical adjustment.

But you think you’ve adjusted to it now?

Oh, I’ve adjusted to it now! I don’t think I’m in control, but I’m more equipped to deal with all the changes that come. And there are people that help you along that I’ve developed over the years.

Like Brad?

Oh, yes. He’s my tentpole.

It’s got to feel great to have told these stories so successfully, getting them out to a wide audience. It’s a terrific culmination to a long career and eventful life, but life goes on. What’s next for you?

I have so many more tales to tell! Maybe I’ll do another children’s book.

Peter Dabbene