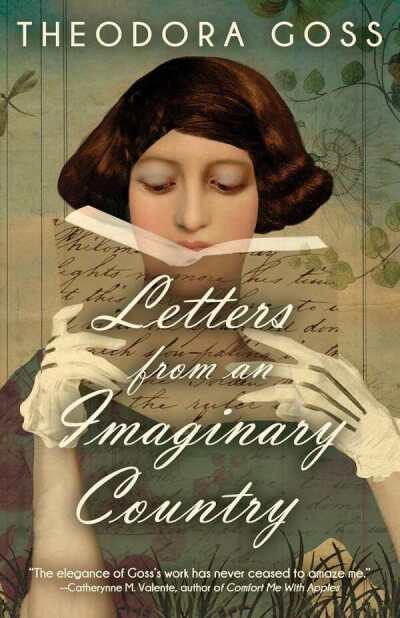

Reviewer Michelle Schingler Interviews Theodora Goss, Author of Letters from an Imaginary Country

As readers, we are fortunate beyond measure to have learned to love reading at a young age because one of life’s greatest pleasures is to fall under the spell of a written story. So, when putting together your Christmas list this year, don’t forget whoever it was that put the first few books in your pudgy hands.

But there’s two sides to every story. An early read of today’s interview with Theodora Goss gave us a peek into the inner life of a gifted storyteller—and we were left a little envious. Dora speaks of her creative process and you can sense the giddiness she feels as her imagination seizes control and takes her on extraordinary adventures. How thrilling it must be to keep the pen moving through it all, to capture it on paper for others to share.

You’re in good hands today. Michelle, our editor-in-chief, reviewed Dora’s Letters from an Imaginary Country in Foreword’s November/December issue and then primed her own imagination to come up with some engaging questions.

We’d be remiss not to mention these three other outstanding short stories collections from the INDIES Book of the Year Awards.

Several of your stories are set in the margins of classic stories from authors including Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, showing compassion to characters who were previously ignored and giving them new life. What fascinates you about the untold stories in these works?

I’ve always been fascinated by characters on the margins of stories. There is a term now—an NPC, meaning a non-player character in a role-playing game. You could go back to E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel and his idea of flat characters—these are the characters who are necessary to make the story happen, but they do not change in the course of the narrative. One example might be Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. I’m fascinated by NPCs and flat characters because they don’t exist in real life—in real life, every person is the main character of his or her own story, and it would be fascinating to read an autobiography of Mrs. Bennet. What did she think, what were her motivations? How did she grow up, to create the habits and anxieties we see her have in Austen’s novels? Dickens was actually very good at giving roundness to characters that might just have been NPCs in other novels.

And I’m always interested in characters that are silent—that don’t get to say much, or perhaps anything. Why are they silent, or even silenced? What is the author not letting them say? When I was a graduate student, I took a class on Jane Austen. One assignment was to write an essay about a minor character—I chose Anne De Bourgh, who literally says nothing in Pride and Prejudice. She might cough once or twice? My short story “Pug” is about giving her a voice and thinking about all the other NPCs in literature.

If you could yourself switch places with a famous character for a week, who would you choose and what would you do in their shoes?

Do you mean in spirit or physically? Because one question is about inhabiting the body of a character, while the other is about inhabiting their world. If I could switch places with a character in terms of being that person for a week, I would want to be a younger version of Miss Marple. Partly because I would like to see what her life was like, as a young woman, and partly because she has such an acute mind—she is one of the best observers in literature. If you were going to inhabit the body of another person, you would want it to be a person who notices everything. But if I were able to switch places with another character in terms of actually physically being someplace myself, it would be literally anyone in Narnia. Just to be in Narnia.

In Come See the Living Dryad, a woman with a genetic condition investigates her ancestor’s marginalization and murder. What is it about the sideshow realm that fascinated you, and was there catharsis in giving silenced Daphne a second chance for justice?

I researched sideshows when I was writing my doctoral dissertation on 19th century gothic fiction. The people who were in those shows are fascinating. On the one hand, they were often socially marginalized. On the other, they could gain a measure of freedom and financial security, if they could control how they were presented and their own performances. The shows and the communities around them are much more complex than we imagine. For example, Fedor Jeftichew, a Russian man who performed under the name “Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy,” came from a family with hereditary hypertrichosis. His father was also a sideshow performer—it was a bit like belonging to a Vaudeville family.

Anything that crossed species and gender boundaries was fascinating to the Victorian public, so there was an entire subgenre of Bearded Ladies. Paradoxically, the Bearded Ladies were presented as particularly feminine—they would do things like display their embroidery for the audience. These performers acted out social anxieties. I suppose in the same way I was fascinated by marginalized characters and wanted to tell their stories, I was fascinated by these real people, who lived at the margins of Victorian society—and yet, that margin was also at the center, because it reveals what society at that time found both irresistible and troubling. And yes, it was cathartic giving Daphne a voice—I think it always is for an author, when you let silenced characters speak.

In your dazzling autobiographical novella, you interact with the version of yourself who stayed behind in Hungary. It’s such a piquing way of considering paths not taken! Do you also imagine other Doras out in the universe, and how do you interact with their possibilities?

I suppose I do, because I also put myself, in some way, into two other stories in the collection: “Letters from an Imaginary Country” (which includes a character named Dr. Goss, who is a scholar of Thülian folklore) and the final longer story, “The Secret Diary of Mina Harker” (where I drew on some autobiographical details to create the protagonist, Dorothy Nolan). I suppose it’s my way of acknowledging that I am always in my stories in some way—they are never not about my ideas and perceptions. The author is always in there somewhere. But on the other hand, when you write a story, you also suspend your own personality and history to channel other things—you try to inhabit other characters, other settings. You write things that never happened to you. It’s a mysterious balancing act, and I don’t know if any writer understands quite how it works. There is a kind of joy and relief to getting outside of yourself, to inhabiting another self and world. I loved being Anne and Estella and the poet Elah Gal. I also like to get away from being Dora for a while…

In several of your tales, academics and young students imagine whole nations, with rich histories, into being. What are the responsibilities of such creators toward their creations, and do you feel similar responsibilities to your own characters?

I do feel a responsibility to my own characters. It is not always to make them happy, but it is to give them depth and richness—to allow them to really live. And to give them meaning, perhaps in lieu of a happy ending. As for creators of nations and societies—that’s all of us, really, right? I mean, all of us together imagine whole nations into being, because nations are in the end imagined constructs. That doesn’t mean they aren’t real—they include real reality (actual rivers and mountains) and also what Yuval Noah Harari calls intersubjective reality (the reality we human beings mostly agree exists, such as borders and currency and governments). We are all responsible for the societies we live in—for making sure that they are just, and people can live in them well, and they do not invade or colonize or destroy other societies.

The academic field of imaginary anthropology, which I wrote about in “Cimmeria” and “Pellargonia,” is fun to play around with, but in the end all human societies are created through imagination—through storytelling in various forms. So I suppose the stories are also metaphors. I as the author don’t want to think about them in that way—someone else (a review? a literary critic?) can do that work. I’m just here to write a story about a group of characters that did something, and what happened because of it.

This is a rich collection that spans multiple genres, with bold inventiveness as its throughline. Can you talk about the process of winnowing short stories down for a collection—deciding what fits, what must be held for next volumes, et cetera?

I actually first submitted a different collection to my wonderful publisher, Tachyon Publications. They told me it didn’t work, and they were right. I took out about half the stories, and I created another collection specifically of retold fairy tale short stories and poems—it’s called Snow White Learns Witchcraft, and it was published by another wonderful small press, Mythic Delirium Books. I loved how that collection had real coherence and flow, and readers seemed to like that it focused on specifically what they were looking for, which was retellings of traditional fairy tales, usually from a feminist perspective. After that I wrote a few more stories that somehow seemed to fit together, and I asked, what am I doing now? What is on my mind? The central point seemed to be metafiction—looking back at older stories and retelling them (as in “Estella Saves the Village”), but also thinking about story itself (as in the two imaginary anthropology stories). What is storytelling? What does it let us do? It was me being meta (as in metacognitive, metaphysical) about fiction. I put together a new collection, with two new stories, the titular “Letters from an Imaginary Country” and “Dora/Dóra: an Autobiography,” sent the manuscript to Tachyon, and they liked it. They asked me to drop one older story I had included and write a new monster story, which became “The Secret Diary of Mina Harker.” And that became the collection.

No one is going to finish this book and not want more of your work. What are you working on next?

I’m working on a novel! I’m doing the same thing I did with “The Mad Scientist’s Daughter,” the first story in this collection, which eventually became my Athena Club trilogy: The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman, and The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl. Years ago, I wrote a story called “Pip and the Fairies” about a woman named Philippa whose mother was a writer. She wrote a series of children’s books, starting with “Pip and the Fairies,” about a little girl who meets and goes on adventures with fairies. Now, years later, Philippa doesn’t remember if she actually met fairies or not—she has a vague memory, but are they formed by having read her mother’s books? Or was she actually the Pip who went on those adventures? The novel is about Philippa returning to the town in Maine where she and her mother lived as a child. She is about to find out what actually happened, and whether the fairies are real …

Michelle Anne Schingler