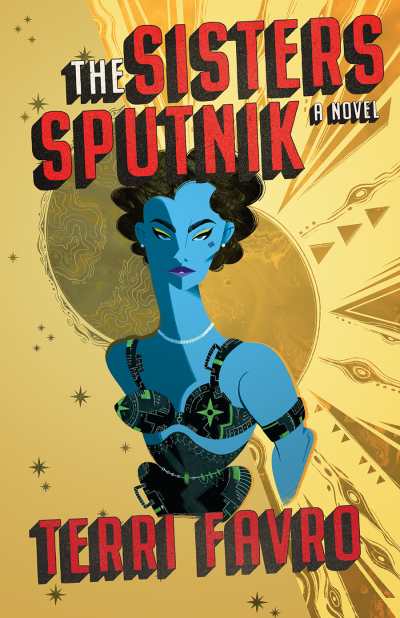

Reviewer Michelle Anne Schingler Interviews Terri Favro, Author of The Sisters Sputnik

This week, let’s take a break from the angst of current events … to talk about a fictional world burdened by the threat of nuclear war, villainous robots, raging viruses, and all manner of crazy shit. But Terri Favro makes this setup even more diabolical by subjecting her universe to cosmic leaps of time every time a nuclear blast goes off, from Hiroshima forward, including hundreds of test detonations.

So, yes, in The Sisters Sputnik, she’s got the multiverse thing covered twenty five hundred times and counting, and her characters are dizzied to no end as they slip in and out of one world after another. Time waits for no one.

Mesmerized by her starred review of The Sisters Sputnik, we asked sci-fi fanatic Michelle Schingler to track Terri down for a chat. As you’ll see, they had a blast.

Most multiverse novels spin from the theory of infinite universes; in yours, there are limited alternate universes, and each is the result of an acute act of human violence (a nuclear explosion). What inspired your singular approach to his subgenre?

Both The Sisters Sputnik and its prequel, Sputnik’s Children, were inspired by my childhood nightmares about the atomic bomb. I grew up on the US-Canadian border in a place once known as Grantham Township, now part of the city of St. Catharines near Niagara Falls, Ontario. (Grantham was home to many immigrant families from southern and eastern Europe, as well as African-Canadian families whose ancestors arrived in the region via the Underground Railroad with the help of Harriet Tubman, who lived for a time in St. Catharines. The community is called Shipman’s Corners in my novels.)

During our Saturday morning cartoons, we endured the high pitched whine of drills of the Emergency Alert System from across the border in Buffalo, telling us to prepare ourselves to “take cover” in the middle of the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show which, of course, featured bumbling Russian spies Boris and Natasha. Saturdays were a weird clash of candy and cereal commercials, cartoon fun and terrifying reminders that we could be vaporized in the blink of an eye, all washed down with a glass of Tang orange drink.

The hydroelectric station at Niagara Falls was a first-strike target, so we believed that one day, out of a clear blue sky, we’d be among the first to go (unless we got to live on the Moon first)—a thermonuclear World War III seemed inevitable. Instill that level of fear in a generation of children and it becomes muscle memory: we really were the children of Sputnik. No wonder we liked comic books so much—they reflected a mutant version of reality that we thought would probably turn out to be true.

So, in The Sisters Sputnik, every atomic blast—Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and all the test detonations before and since, a little over 2,000 of them to date—births a new timeline in the multiverse. I think there’s truth in that scenario. Every nuclear blast takes us closer to living in an altered (if not alternate) world, by moving us one minute closer to midnight on the Doomsday Clock of the Atomic Scientists. That seems as likely an explanation for the multiverse as the Many Worlds theory of quantum physics that gave us the trope that there are an infinite number of alternate worlds.

Debbie finds herself stranded in a timeline where she, like too many refugees, is feared and resented—with the added suspicion brought about by a plague that coincided with the collision of people from different timelines. And when she winds up in the past, she witnesses the same viciousness applied to outsiders, coming from nationalists in the pre-nuclear age (she and Frank Sinatra commiserate over this fact). There are multiple real world evocations here, of course. What hope do you see for people being able to look beyond these historically recurrent base fears and Otherings?

I’m tempted to misquote Bones and say, “Dammit, I’m a science fiction storyteller, not a fortuneteller,” but in truth, I haven’t been this frightened about our future since the Cold War (supposedly) ended. It feels like a Gort moment: the intergalactic law enforcement robot from The Day The Earth Stood Still visited Earth to warn us that, now that humanity had nuclear arms and was pushing out into space, we were perceived as threats to the rest of the galaxy. Either give up our self-destructive ways or Gort would do the job for us in a blast of radiation. Good riddance, as far as the galaxy was concerned.

And yet I do have hope: the very fact that we talk now about “‘Othering”— that we have a word for being treated as “other than” fully human—gives me hope. Thirty, forty, fifty years or more ago, those being othered were invisible or treated as existing outside the mainstream of “normal” human existence. So I have hope, yes, because our language has changed to embrace a concept of inclusivity and diversity that didn’t exist until recently. But I have to say that my fear of nuclear war, the destruction of democracy, the rise of (as I put in my novel) “Mussolini wannabes,” and the world being cooked alive like a medieval martyr, hasn’t abated. The recent racially-motivated mass shooting in Buffalo by a proponent of white replacement theory also seems chillingly similar to certain events in my novel. Even as we progress, we regress.

Debbie’s comic series is her source of income, fame, and security in her adopted timeline. Once she’s forced to write someone else’s story, though: her writing also becomes a potential source of great harm. Is there a message about the power of words—and about the responsibilities of those who wield words for public consumption—implicit in the tensions between her various projects?

Debbie has her feet in two worlds—not only her home world of Atomic Mean Time and our world of Earth Standard Time, but the worlds of art and commerce. That’s a balancing act I’m familiar with, having worked as a freelance advertising copywriter as well as a novelist and pop cult essayist. My freelance work helps support my art. The same holds true of Debbie, but in her case the stakes are much higher. She is, after all, a Destroyer of Worlds.

Even though she sacrificed herself and her Past to save the people of Atomic Mean Time, she isn’t immune to the temptation to sell her soul for profit. She steals ideas from a 1950s propaganda comic strip for her own gain: this isn’t chump change, we’re talking Non-Fungible Assets on the blockchain, baby! When she travels into the past and is forced to produce the strip, it turns out she’s actually responsible for the strip existing in the first place. What started as exploitation of an obscure comic strip turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In researching the book, I looked at propaganda comics of the past, especially the 1930s through 1970s. A number of them used the Funny Pages to communicate their creators’ political views, just like in Futureman. In my novel, art does imitate life. It’s like going back to those Saturday mornings of my childhood: Looney Toons mixed with nuclear preparedness drills.

Why does Debbie find it so hard to forgive an old friend’s turn toward synthetic comfort in his adopted timeline?

Well, first of all, her lover David lied to her: in the first chapter, she asked him up front whether the robot in his pantry was a “Dutch wife,” which is an archaic term for “sex doll.” David knew Debbie well enough to realize that she would not react well to Jenny’s true purpose.

Secondly, Debbie and David met in a timeline where they were being held captive by a race of sentient robots. David having a robot as a lover would seem like he was sleeping with the enemy.

Lastly, Debbie is self-centered—she wouldn’t want to find herself sharing David’s bed with a silicon life form. Fond as I am of robots, I would feel the same way.

Obligatory multiverse author question: what would you like to think that a version of you is doing right now in an alternate timeline?

I hope that in some other timeline—let’s call it Wish Fulfillment Time—I am a roboticist. I’m the math and science genius I never was in Earth Standard Time. Although most of the robots in The Sisters Sputnik are nasty pieces of work, I, for one, welcome the age of artificial people. They are our silicon children, aren’t they? Maybe instead of replacing us, they’ll save us from ourselves (like in some Asimov’s I, Robot stories). So I say to Professor Favro of Wish Fulfillment Time: “Klaatu barada nikto!”

What are you working on next?

I’m in the middle of writing an epistolary Steampunk novel called The False Queen’s Archive, made up of interview transcriptions, letters, journals, and an unfinished screenplay about a Great War of Reunification to return the United States to the bosom of the British Crown. You could think of it is a Steampunk-infused reimagining of the War of 1812 with Victorian robots.

I’ve also started writing a third book in the Sputnik Chick series with the working title Prima One. Prima is the biomechanoid child at the end of The Sisters Sputnik. She’s trapped in the 1950s with her caregivers Eufemia and Ralph De Marco (who are seniors in The Sisters Sputnik). Of course, they have foreknowledge of the future, especially of the 1960s, when they were young adults. It’s an opportunity for me to visit that era (and maybe drop in on Sinatra in his Las Vegas years). Prima, who is more evolved than a mere human, is perceived as a disabled child in the 1950s, but she goes on to have a powerful impact on America of the 1960s.

Check out our Petit Foreword videos with Margaret Renkl, André Alexis, Richard Dawkins, and many other talented writers conversing with our top editors, Michelle Anne Schingler and Danielle Ballantyne: https://www.youtube.com/c/Forewordreviews

Michelle Anne Schingler