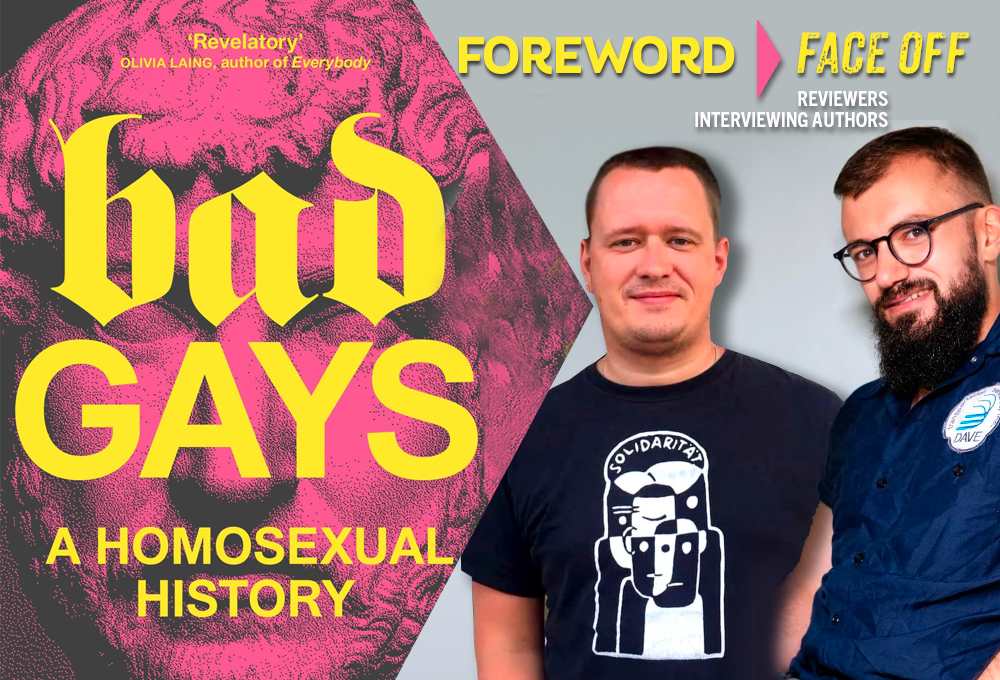

Reviewer Michal Elias Interview Ben Miller and Huw Lemmey, Author of Bad Gays: A Homosexual History

If your pug does a job on your Persian rug, you’ll certainly let him know she’s a Bad Dog! And, don’t feel sorry for yourself because just about everyone also has an uncle with Bad Breath! Oh, and let’s not forget about those hellions in high school—you may have had a crush on one—known as the Bad Boys!

Well, now it’s our pleasure to introduce Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller, authors of Bad Gays, a stunningly original project and one we couldn’t pass up in Foreword This Week. In his review for Foreword’s May/June issue, Michael Elias writes that this Homosexual History is “about prominent historical queer figures whose ‘evilness’ is often overlooked when discussing the history of queer politics, and whose queerness is often overlooked when discussing the history of ‘evil’ politics.” Not bad, Mike, nicely put.

So, let’s do this!

You started the work on Bad Gays as a podcast before writing the book, and these are two mediums that engage with audiences on different levels. Can you talk a bit about the process of transitioning from Bad Gays the podcast to Bad Gays the book?

We wanted to maintain the voice that we developed over years of making the show, which is a studied mixture of intellectual rigor and humor. Since part of the show is an attempt to bring academic and activist conversations to a wider audience, we find that mixture to be particularly important in terms of bringing an audience along and getting them to internalize complicated ideas through jokes and through showing how complicated structures work them out in the space of a single life. The book and the show have pretty much the same tone, we think that mainstream audiences are ready for this kind of grownup, smart, but still casual and engaging conversation about queer history.

Where did your interest in the “bad gays” of history come from, and why do you think it’s so important to talk about them now?

Bad Gays have often, unfortunately, had just as big an effect on the meaning of what it is to be gay in the creation of a gay identity itself as the heroes that we typically like to remember in public queer history. Both of us believe that we need to learn more about the ways in which we have gone wrong in order to understand how we might, in the future, go right.

Did anything in your perception or understanding of the figures you wrote about change as you researched them? Did that affect your idea of who and what “bad gays” are?

We like to joke that some of the people in our book are bad people who happen to be gay, some of them are people who were bad at being gay, and the rest are just complicated. Over the course of the show we have realized that there are more bad gays than we thought and that they were even more influential than we thought in how the figure of the homosexual, specifically the white male homosexual, came to be.

You state that you decided to use present-day terminology throughout the book “as a way of putting today’s homosexuality under a microscope.” Modern-day terminology is a contested subject in historical writing and you acknowledge that while using it; that feels liberating and fitting for the thesis of the book, which is more about the future and the present than the past. When did you make the choice you made and how did it affect the process of creating Bad Gays?

We wrote the book as a history of the present, about a series of usable and abusable past that help explain how we got where we are today. It was an easy decision for us to use present day language, as we felt it helped us make the stories more current and more accessible. That said, we’re always careful to show our work when we apply present day concepts to the past and explain why we think we can learn something by doing so. Our audience is then free to agree or disagree.

Who is your favorite “bad gay” and why?

Ben: Mine would be Roger Casement, because he was an anti colonial activist and also because he was extremely hot.

Huw: Pietro Aretino, a brilliant satirist who was so good at taking down his targets that both the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor hired him to blackmail the other. He parlayed that skill into a beautiful palazzo on the Grand Canal in Venice. Anyone who gets rich and famous being a writer is a hero of mine.

You talk a lot about the need for solidarity between people and communities in the book. What would you say was the biggest lesson for you about solidarity while researching and writing?

That solidarity has to be acted upon every day, and that the people who are the loudest about how good they are are often the least active at doing it.

Michael Elias