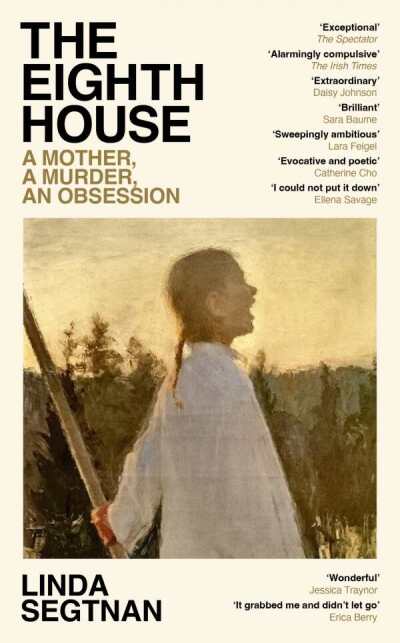

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Linda Segtnan, Author of The Eighth House: A Mother, a Murder, an Obsession

We’re always keen to discover fantastic true crime books, especially when the writing pushes beyond journalism’s who, what, when, where, and why and proceeds to deliver all the atmosphere and elegance of great storytelling. No, it doesn’t happen very often but we sensed The Eighth House was special when Meg Nola’s review hinted at the “intense psychological effects” Linda Segtnan—a pregnant mother at the time—experienced while researching the murder of nine-year-old Birgitta Savander in rural Sweden in 1948.

Meg writes that Linda became obsessed with the crime during her research—she “sensed supernatural presences and explored Birgitta’s astrological chart [and] while this mysticism heightened Segtnan’s intuitive awareness, she also felt overwhelmed with anguish and frustrated by her inability to find definitive answers.”

In a word, The Eighth House is “haunting,” Meg says, so we’re certain fans of true crime will be thrilled.

With compelling women and their stories top of mind, check out these two 2024 INDIES winners in the Women’s Studies category: Paths Made by Walking (gold), and The Doctor Was a Woman (silver).

You were doing research at the National Library of Sweden when you noticed a 1948 newspaper article about the murder of Birgitta Sivander. In the accompanying photo, nine-year-old Birgitta wore a big bow in her hair and her eyes seemed as “deep as wells.” After reading about her death, you felt yourself being drawn into the still-unsolved crime—you noted that your reaction was almost visceral, or like a “conception.” You were also a relatively new parent at the time following the birth of your son, Sam. How did having children influence your decision to research Birgitta’s murder?

I think it is unavoidable that your reaction to child abuse changes after having children, or having a close relationship to a child. All parents I have spoken to about this say that reading or watching something related to children being mistreated affects them on a deeper level than before having children. But something in Birgitta’s eyes just grabbed me and wouldn’t let go; I can´t really explain why, even though I try to in my book. When I found her, the case files were still classified. I had to wait a year for the investigation to become public. During this time she stayed with me. For lack of a better word, I would describe it as an obsession. It was an overwhelming feeling that I had to help her. I think being a mother most likely made it easier for her to find me, so to speak, and my protective feelings towards her only intensified when I found out I was pregnant again (at the same time that I got access to the case files).

You describe the city of Perstorp, where Birgitta lived and where her body was found, with insightful historical detail. By the late 19th century, Perstop had changed from being a “farming village” to a bustling industrialized area. After World War II, refugees from Sudeten Germany, Poland, and Hungary arrived to fill the many available factory jobs. Yet there seemed to be an underlying mistrust of these migrants, particularly in the aftermath of Birgitta’s murder. How were the foreign workers treated by the Swedish police during the investigation?

They were not treated the same way as the locals, that’s for sure. From the very beginning there seemed to be some collective notion that this heinous act must have been committed by a “stranger.” The police had no reason to suspect a migrant worker; still it was the first place they looked. They checked all their shoes, but no one else’s it seems. The boy who became the prime suspect had a German father, which might well have led the investigation to focus on him, instead of more likely suspects, but obviously I can’t know that for sure.

You add fictional breadth to Birgitta and her family, imagining her last day of life at home and the exploratory enthusiasm that made her venture out on a “pink and shimmering” spring evening. You also offer earlier impressionistic glimpses, like how she perhaps enjoyed eating “cheese sandwiches after a long day of playing,” then went to bed “with an adventure book in her hand.” What was your process of fleshing out Birgitta’s personality and making her more than a tragic murder victim?

Most of what I know about her comes from interviews with Birgitta’s brother. Some glimpses from witness interviews and the trial, some from newspapers at the time. It can be likened to a puzzle where I had some of the pieces, but had to fill in the gaps. I did so intuitively, and was then surprised by how much, according to Birgitta’s brother, matched his memories of his sister.

While you were working on the book, you experienced panic attacks and feelings of emotional vulnerability and depression; you even began to sense “palpable,” ghost-like presences in your home. Yet this psychological and mystical sensitivity gives the narrative an added dimension, just as how your research into Birgitta’s astrological eighth house placement provided the book’s title. How can a person’s eighth house zodiac position be significant and what did you discover about Birgitta’s chart?

My grandfather, who was a devout Christian, but also a man of science used to say “I’m not so dumb that I think I know everything.” This is of course more or less the basis for all scientific research, but I think there is more to this sentiment than that. Things we can’t explain still affect us. Often more than things we can explain. Were there actual ghostlike presences in my home? That is kind of beside the point. I sensed something, and the sensation was most definitely palpable. That happened, and nobody can say I wasn’t affected by it.

I was very open to everything while writing this book, because I was desperate for answers—any answers. I learned that in astrology, the eighth house supposedly tells you how you will die, and Birgitta’s chart foretells a sudden death, possibly from injuries to the back of the head. It also speaks of murder, violence, and evil, and that really struck me.

Through your internet research, you were able to contact and befriend Birgitta’s brother, Karl, who was then in his eighties. But you note how the Perstorp Facebook group was “dismissive,” “defensive,” and even “angry” in response to posts requesting information about Birgitta’s murder. Why do you suppose they reacted like that and have you gotten any feedback from the area since the book’s publication?

After I posted in the group one man reached out to me. He had grown up in Perstorp and told me it would probably be hard to get anyone to talk about the murder. He said that there is a culture in Perstorp of putting the lid on things. This is hardly unique to Perstorp, but it might be more prevalent than in other places. In any case, this murder affected the entire community in a way I can’t really claim to fully understand, since I’m from a larger city. But it seems it became like a wound that nobody dared to touch.

Now, some seventy years later, I can see how you would be reluctant to take the band-aid off, so to speak. Who knows what’s under there? Wounds tend to fester. I have very deliberately avoided the Facebook group after the book was finished, but I have received some messages. Only one angry one, really. I don’t know if that many of Perstorp’s residents have read the book.

Though sexual and homicidal violence against children will shamefully continue, does it seem that advanced DNA testing and technological tracking (via cellphones and surveillance cameras) offer much better chances of solving murders like Birgitta’s today?

Well, that goes without saying, but at the same time some things are probably very much the same. I believe the same kind of prejudice towards foreigners and even people with immigrant parents is as common as in the 1940s. If Birgitta was murdered today, they would most likely check the DNA of the migrant workers first. Or something to that effect. But I would hope that the fourteen-year old main suspect would have been written off as the perpetrator by examining the small blood stains on his clothes.

Are you working on any new projects that you’d like to share?

Yes, I am working (and am hopefully done very soon) on a novel called The Fisherman. It will be out in Sweden in January. It is very loosely based on the haunting of a forester’s wife that took place early in the last century. There was an investigation conducted by a famous psychiatrist who wrote a book about the case, so it gained some notoriety at the time but is pretty much forgotten now. In general, spiritism was kind of in fashion at the time and hauntings were taken a bit more seriously by “actual” academics. I started out thinking I was going to write some sort of ghosty thriller, but it has morphed into something entirely different. Gradually, while writing the book, I found that the “ghosts” might no longer be what they initially seemed to be.

Writing it has come with a completely new set of challenges. In The Eighth House the challenge was to depict something as historically accurate as possible and getting as close to the truth as possible. That was challenging in its own way, but at least I knew, in broad strokes, what had happened when and where. In The Fisherman I’ve had to deal with this very annoying thing called “plot.” It turns out to be very hard to know if something is “tense, suspenseful, and chilling” when you know exactly what is going to happen. I usually let my husband be some sort of first test audience, but since we’ve discussed the plot extensively beforehand, he is of no use to me anymore. Luckily, I have a very, very good editor.

Meg Nola