Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Donna Barba Higuera, Author of Alebrijes

Her mind has many minds of its own. Donna Barba Higuera, welcome to Foreword This Week—your new fantasy novel, Alebrijes, earned a starred review from Meg Nola in our November/December issue and we’re dying to discover secrets of your ingenuity.

When did you first realize that you wanted to become a writer?

I don’t think I ever sought out becoming a writer in the sense it would become a profession. But I

knew from a very young age that I wanted to tell stories. My first “story” was a UFO fabrication that I swore was true to my elderly next door neighbor and parents. I was five. That was the beginning. Around the age of eight or nine, l began writing my “fabrications” in a notebook. I suppose that was when I knew writing was part of who I was.

The novel’s narrator, Leandro, is a 13-year-old orphan who does his best to care for his younger sister in a ravaged world. Leandro is also a skilled pickpocket, though this is balanced by his perceptive compassion and occasional sense of remorse. But isn’t it really Leandro’s craftiness of character that makes him the ideal hero for the book?

I hadn’t thought of Leandro being cunning in any way. I guess I thought of him more as being a survivor. I fashioned his character out of the people I grew up around—the field and farm workers alongside the oil field workers of the Central San Joaquin Valley in California. I always admired those who came before me, as well as those just like them who still live there. They work hard. They overcome so many obstacles most will never comprehend. Life was, and can still be, hard for them.

I viewed Leandro more as a survivor, but I suppose you’re right. Oftentimes, survivors must be cunning. Even the tale I made up of the Cascabeles begins with them being calculating enough to dig into the hills to survive Earth’s demise. Crafty, with a will to survive. I suppose Leandro is also both of those things.

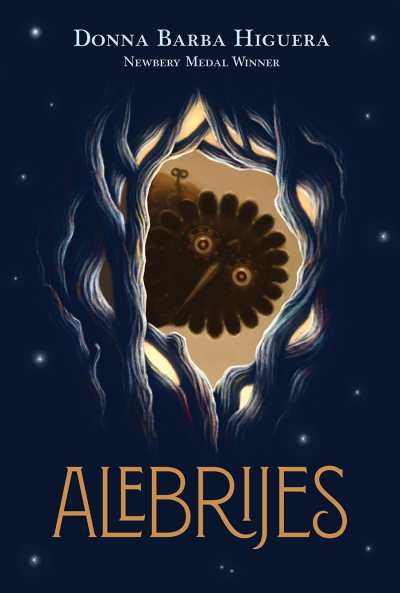

Alebrijes has such wonderful, fantastical elements, from the dragon-like wyrms to the stag beetle currency, to the Center of Banishment, the Mongers, and the Tree of Souls. And then there are the alebrijes themselves—like the owl, hawk, bear, cat, tortoise, and Leandro’s hummingbird—all mechanical, magical drones energized with the minds and “consciousness” of individual humans. What’s your process of world-building in your fiction?

I don’t really have a process. I wait for the ideas to arrive. And boy, do I get some strange ideas! Still, I go with it.

The idea of the wyrms came about when I was writing about the region of Pocatel. I was imagining the deception that ran beneath the valley’s surface. I imagined how the lies of its leaders would play out and slither just under its surface. And the wyrm was born.

The copper stag beetle currency was a mix of what the Pocatelans might value that we don’t at this time. Beetles would have value in their use as a protein food source. Ewww. But also, the valley in Idaho that I based the setting on was once a smelting hub of silver, copper, and other metals. A copper beetle had both a great visual and felt very real to me.

Most of my ideas spring from one small thing I overhear or read. But my imagination twists then blows it up in odd ways. Each idea I incorporate gives me goosebumps or makes me feel strong emotions. If it doesn’t, I don’t include it.

Leandro and his sister Gabi are Cascabel and regarded as an underclass by the Pocatelans. The tenacious Cascabeles are close-knit and identify strongly with rattlesnakes, even carving snake-like scars onto their necks to mark the deaths of loved ones. While this gives them a sense of collective pride, they are also accused by others of being “meant to slither in the dirt,” with eyes that “speak evil.” What was your inspiration for the Cascabeles?

I love this question! This is one of those ideas that gave me the strongest of emotions and also goosebumps. Cascabeles is short for serpientes de cascabel, which means rattlesnakes in Spanish. And the people I based the Cascabeles on … those field workers and oil field workers? They were surrounded in the desert of the San Joaquin Valley of California by … rattlesnakes! Gasp!

Rattlesnakes are very much a part of the environment there. Most writers draw from wounds or deep emotions, and sometimes we don’t even know we’re doing it. I had a childhood trauma with a rattlesnake. That’s a story for another day.

But I decided to purposefully take that thing that terrified me and turn it around and embrace it. I would even give it power. It felt uncomfortable, but like the right decision, and now I’m glad I did.

The novel keeps certain words or phrases in Spanish without translation, like when Leandro encourages the “semilla” or seed potato to grow, or when the Cascabeles sing their “Canción,” vowing to rise above their present fate and someday triumph. This is integrated deftly and enriches the narrative throughout—is there a particular rhythm of bilinguality that flows while you’re writing?

Not always. But with this book in particular, it did. I imagined I was overhearing conversations from that part of my family and the people who worked where I grew up. But when incorporating Spanish, certain words and phrases make more sense to me in Spanish. Others have no translation at all. (Full admission, I don’t write or read well in Spanish. I’m learning to put my ego aside, and I’m reading picture books and early readers in Spanish now to improve both my spelling and reading skill.) But when I’m writing, I put it on the page how it sounds naturally in my mind, which is mostly Spanglish. In the end, I wrote the songs, dialogue, and retold stories how I imagined the characters would four hundred years after they rebuilt themselves into something new.

Leandro’s tiny drone is inscribed with the phrase, The smallest flap of wings can change the course of history. How do you think this applies to our current world situation?

The world is the scariest of places currently. Far scarier than when I first wrote Alebrijes. I don’t recall in my entire life the world ever feeling as frightening as it does now. And kids today see so much more than most of us did as children. Technology feeds flashes of horrific images in front of them constantly.

I was a child who worried a lot. I worried about the future. I worried about what I would become. I worried about what might happen to me. I worried about the people I loved. I know there are young people who are anxious and feel deeply like I had.

And just as I had, young people often feel too small, too young, and powerless to make change. I wanted to write a character who feels like they do. One they can relate to. But I also wanted to show how Leandro, in the smallest of physical forms, so young, feeling powerless, was able to change the world around him.

Leandro’s world in Alebrijes, presents insurmountable challenges. Much like our own world today, one in which we can feel so powerless, we still need to have hope. Hope that we can change the parts of the world we fear the most.

Meg Nola